Our discussion on Hunted touched on: genre (including melodrama and noir); the male melodrama and its reliance on mystery, violence, and chase; the main character Christopher Lloyd (Dirk Bogarde) as both villain and victim; Bogarde’s screen and star images; the relationship between Christopher and the boy Robbie (Jon Whitely) and other films with similar adult/child relationships; the way Christopher’s interaction with, or comparison to, other characters further illuminated his own personality; the film’s social commentary on the harsh realities of life in Britain post WWII.

We first noted a few moments in the film which seemed especially melodramatic in terms of heightened emotion. These included the tense moment at the film’s opening as 6-year-old Robbie (Jon Whiteley) stumbles across Christopher (Dirk Bogarde) after the latter has committed murder in a bombed out cellar; a courting couple’s discovery of the body of Christopher’s victim in the same location; Christopher’s display of emotion when he breaks into his flat and confronts his wife. Most of these were underscored by intense music.

We first noted a few moments in the film which seemed especially melodramatic in terms of heightened emotion. These included the tense moment at the film’s opening as 6-year-old Robbie (Jon Whiteley) stumbles across Christopher (Dirk Bogarde) after the latter has committed murder in a bombed out cellar; a courting couple’s discovery of the body of Christopher’s victim in the same location; Christopher’s display of emotion when he breaks into his flat and confronts his wife. Most of these were underscored by intense music.

The film’s use of real locations and its stark black and white photography were also commented on. These spoke to the film’s function as social commentary, and its film noir overtones. We discussed at length the ‘male melodrama’ Steve Neale has written about in his work on the term ‘melodrama’ in contemporaneous trade material.

We noticed that there was little of the first of the three elements considered important to the male melodrama – Mystery. The film was clear from the start that Christopher was guilty, with the audience in a far more privileged position of knowledge than the police, although it was unclear what the fate of the characters would be. Given Christopher’s crime, especially in the context of 1950s films, it seemed unlikely that he would escape unpunished.

The second of the important ingredient for male melodrama, violence, was more present – and in a few interesting ways. The most extreme of this occurred before the narrative began, taking place off screen. We do not see Christopher’s deadly attack on his rival, nor the abuse directed at Robbie by his father. The violence shown is fairly muted. Christopher is a little rough with Robbie at first – not wary of physically moving him. Christopher also strikes his faithless wife and gets into a tangle on a staircase with a policeman who is on the lookout for him at his block of flats. Later, Christopher unceremoniously thrusts the well-meaning Mrs Sykes (Kay Walsh), who is concerned about Robbie, into a garden shed. While the fact we never see Christopher land a punch may be due to censorship or norms of the time as to what was depicted, we can also perhaps connect it to Dirk Bogarde’s screen and star images. He may have been less likely to engage in on-screen violence in comparison to other male stars of the time.

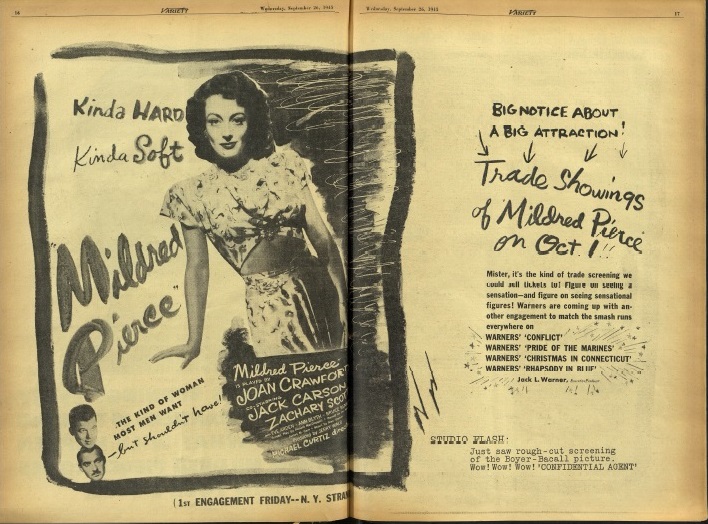

Chase (the third aspect of the male melodrama) was the most present. Indeed, this was commented on in reviews of the time in relating to melodrama. This included the observation that some of the chase (the action stretches for several days across London, the North of England, Scotland and an attempt to reach Scandinavia) was less then credible (Variety, 5th March 1952, p. 6). It is important to note that while Christopher is a man on the run with a child, they start out on the run separately – multiplying the ‘chase’ element of the film. The chase moments when Christopher and Robbie were together were the most effective, however. After being discovered by Mrs Sykes, Christopher jumped from a railway bridge onto a moving train and Robbie followed, providing a particularly tense moment.

Chase (the third aspect of the male melodrama) was the most present. Indeed, this was commented on in reviews of the time in relating to melodrama. This included the observation that some of the chase (the action stretches for several days across London, the North of England, Scotland and an attempt to reach Scandinavia) was less then credible (Variety, 5th March 1952, p. 6). It is important to note that while Christopher is a man on the run with a child, they start out on the run separately – multiplying the ‘chase’ element of the film. The chase moments when Christopher and Robbie were together were the most effective, however. After being discovered by Mrs Sykes, Christopher jumped from a railway bridge onto a moving train and Robbie followed, providing a particularly tense moment.

Unsurprisingly, much of our discussion centred on Christopher. He is both villain and victim. His villainy is established very early on (he has, after all killed a man) and it is significant that the film does not seek to overturn this assumption – for example by revealing that while Christopher may have believed he killed the man, in fact the deed was committed by another. Christopher’s actions cause him to be a victim – he is relentlessly, if somewhat incompetently, pursued by the police. We also commented on the fact that because we spend so much time with Christopher, as well as see his growing friendship with the vulnerable Robbie, he is a rounded and sympathetic character.

Christopher’s small acts of kindness are evident from near the start. He asks a man for a cigarette but hesitates when the man generously offers him his last one. While Christopher plans to use Robbie to retrieve money from his flat and is angry with the boy when he fails, he still prioritises Robbie’s meal over his own at a café. As their relationship develops, Christopher’s thoughtfulness towards Robbie becomes more frequent. This culminates in Christopher’s final act: he turns back the boat he has stolen, and in which he and Robbie are attempting to escape to Scandinavia, when he realises that Robbie is seriously ill. The death penalty was still in force in the United Kingdom at the time and Christopher could not plead a crime of passion as a defence. He is almost certainly sacrificing his own life for Robbie’s and in so doing claiming a form of redemption.

Christopher’s small acts of kindness are evident from near the start. He asks a man for a cigarette but hesitates when the man generously offers him his last one. While Christopher plans to use Robbie to retrieve money from his flat and is angry with the boy when he fails, he still prioritises Robbie’s meal over his own at a café. As their relationship develops, Christopher’s thoughtfulness towards Robbie becomes more frequent. This culminates in Christopher’s final act: he turns back the boat he has stolen, and in which he and Robbie are attempting to escape to Scandinavia, when he realises that Robbie is seriously ill. The death penalty was still in force in the United Kingdom at the time and Christopher could not plead a crime of passion as a defence. He is almost certainly sacrificing his own life for Robbie’s and in so doing claiming a form of redemption.

Bogarde’s acting effectively conveys Christopher’s dilemma. The man’s concern for the child is at first just solicitous, but when Christopher realises the extent of Robbie’s illness, he becomes more deeply affected. Christopher’s decision is not one taken lightly, or quickly, since, for all its inevitability, Bogarde shows that it has been pondered. Bogarde is also afforded opportunities to play Christopher’s sensitivity at earlier moments in the film. This is perhaps most notable when in reluctantly obliging Robbie’s request for a bedtime story, he inadvertently tells the story of his failed marriage. At first this seems a fairly traditional ‘Once Upon a Time’ tale about a giant who leaves home. As the story progresses, Christopher introduces a princess who clearly is meant to represent his wife. Christopher’s story-telling register slips from third (‘he’) to first (‘I’) person and he becomes upset when he relates that the lovers have parted. Christopher’s sensitivity is therefore displayed in two significant ways: he is shown to be able to relate to a child, and to be in touch with his sadness. It is also more effective than a flashback would have been since it allows us to see how Christopher has narrativized his past so that it makes sense to him. This is also reinforced by Robbie’s response. It is clear that the boy is disturbed that the fairy tale has turned dark so quickly and concerned about Christopher’s display of emotion.

Bogarde’s acting effectively conveys Christopher’s dilemma. The man’s concern for the child is at first just solicitous, but when Christopher realises the extent of Robbie’s illness, he becomes more deeply affected. Christopher’s decision is not one taken lightly, or quickly, since, for all its inevitability, Bogarde shows that it has been pondered. Bogarde is also afforded opportunities to play Christopher’s sensitivity at earlier moments in the film. This is perhaps most notable when in reluctantly obliging Robbie’s request for a bedtime story, he inadvertently tells the story of his failed marriage. At first this seems a fairly traditional ‘Once Upon a Time’ tale about a giant who leaves home. As the story progresses, Christopher introduces a princess who clearly is meant to represent his wife. Christopher’s story-telling register slips from third (‘he’) to first (‘I’) person and he becomes upset when he relates that the lovers have parted. Christopher’s sensitivity is therefore displayed in two significant ways: he is shown to be able to relate to a child, and to be in touch with his sadness. It is also more effective than a flashback would have been since it allows us to see how Christopher has narrativized his past so that it makes sense to him. This is also reinforced by Robbie’s response. It is clear that the boy is disturbed that the fairy tale has turned dark so quickly and concerned about Christopher’s display of emotion.

The complexity of Christopher’s character reminded us of the nuance and ambiguity of the one he played in Esther Waters four years previously. However, fan magazine material from the time of Hunted’s production highlighted the film as the third in which he starred as a ‘fugitive from justice’ (David Marlowe, ‘Bogarde Takes to the Boats’, Picturegoer 25th August 1951, p.8). There are significant differences between the films cited in the article– The Blue Lamp (1950) and Blackmailed (1951) – and Hunted. While Bogarde plays a man of dubious character in all three, it is only the last that ends in his redemption and allows Bogarde the opportunity to display a conflicted character who is sensitive.

The complexity of Christopher’s character reminded us of the nuance and ambiguity of the one he played in Esther Waters four years previously. However, fan magazine material from the time of Hunted’s production highlighted the film as the third in which he starred as a ‘fugitive from justice’ (David Marlowe, ‘Bogarde Takes to the Boats’, Picturegoer 25th August 1951, p.8). There are significant differences between the films cited in the article– The Blue Lamp (1950) and Blackmailed (1951) – and Hunted. While Bogarde plays a man of dubious character in all three, it is only the last that ends in his redemption and allows Bogarde the opportunity to display a conflicted character who is sensitive.

We can consider how the film employs Bogarde in more detail. Of course, the star still gets to display his dashing good looks, but these are at times obscured by a growth of stubble. Furthermore, in terms of the ‘real’ Bogarde, I have previously noted (in the introduction to Esther Waters: https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2018/09/27/melodrama-screening-and-discussion-1st-of-october-5-7pm-jarman-6/ ) that fan magazines discussed his sensitivity. I also commented that this was tempered by the material also mentioning Bogarde’s heroic war record. We can see these two tensions played out in his screen image in Hunted. Christopher’s kindness towards Robbie is balanced by his (pre-narrative off-screen) killing of his wife’s lover. This is reinforced by Christopher’s ‘manly’ job: he is a sailor, a profession almost exclusive to men at the time. His sailing experience is necessary in terms of the film’s plot – it both explains the prolonged absences which have led to his wife’s infidelity and gives him the skills required to sail the trawler at the film’s end. In truth we did not think that scenes of Bogarde as a sailor would have been especially convincing – he was perhaps a bit too refined.

As implied by our focus on the behaviour Christopher displays towards Robbie in order to showcase the former’s sensitivity, the relationship between the adult man and the boy is central to the film. As a child, Robbie judges Christopher on the way Christopher treats him (Robbie) and is understandably not as aware of what is happening as an adult would be. We discussed related films such as David Lean’s Oliver Twist (1948) and Bryan Forbes’ Whistle down the Wind (1961). It was mentioned that Jon Whiteley’s blond-haired innocence was reminiscent of John Howard Davies in the former film, before he meets the criminal Fagin (Alec Guinness). In the later film, Kathy (Hayley Mills) is

As implied by our focus on the behaviour Christopher displays towards Robbie in order to showcase the former’s sensitivity, the relationship between the adult man and the boy is central to the film. As a child, Robbie judges Christopher on the way Christopher treats him (Robbie) and is understandably not as aware of what is happening as an adult would be. We discussed related films such as David Lean’s Oliver Twist (1948) and Bryan Forbes’ Whistle down the Wind (1961). It was mentioned that Jon Whiteley’s blond-haired innocence was reminiscent of John Howard Davies in the former film, before he meets the criminal Fagin (Alec Guinness). In the later film, Kathy (Hayley Mills) is  prepared to accept Alan Bates on her own terms – she mistakes the stranger for Christ. Differences between these films and Hunted were also important. Christopher and Robbie’s dependence on one another turns into mutual affection. This, and especially the images of the adult carrying the child, reminded us of the recent version of True Grit (2010, Joel and Ethan Cohen).

prepared to accept Alan Bates on her own terms – she mistakes the stranger for Christ. Differences between these films and Hunted were also important. Christopher and Robbie’s dependence on one another turns into mutual affection. This, and especially the images of the adult carrying the child, reminded us of the recent version of True Grit (2010, Joel and Ethan Cohen).

We also spoke about how the fact this all unfolds on screen obviates a more suspect interpretation of Christopher’s intentions. The police try to second-guess Christopher’s motives for ‘abducting’ Robbie, speculating that he will use him as a bargaining chip to ensure his own release. However, our view is more privileged. We know that Christopher has not lured Robbie away, and in fact several times tells him to leave. We also see the initial roughness Christopher displays towards Robbie (physically manhandling him) slowly turn to more domestic scenes. During their time on the run, Christopher allows Robbie to keep a woodlouse as a pet, does not admonish the boy for accidentally spilling his milk, and agrees to tell him a bedtime story. While they are chasing across the countryside, Robbie’s grumbles (‘I’m tired’, ‘my legs are sore’, I’m hungry) and Christopher’s grumpy responses have the feel of a parent’s somewhat trying day out with his child.

The only real light moments in the film occur once the pair has arrived at Christopher’s brother’s Jack’s (Julian Somers) in Scotland. After having endured several days of hunger, the pair laughs as Robbie enthusiastically tucks in to a mound of food. The scenes here also show the difference between the two brothers. While Christopher is a murderer, he nonetheless has humanity. By contrast, Jack refuses to allow even just Robbie to stay, unwilling to be ill-thought of by his neighbours.

The only real light moments in the film occur once the pair has arrived at Christopher’s brother’s Jack’s (Julian Somers) in Scotland. After having endured several days of hunger, the pair laughs as Robbie enthusiastically tucks in to a mound of food. The scenes here also show the difference between the two brothers. While Christopher is a murderer, he nonetheless has humanity. By contrast, Jack refuses to allow even just Robbie to stay, unwilling to be ill-thought of by his neighbours.

(It is worth noting that Bogarde and Whiteley again starred together – in The Spanish Gardener (1956, Philip Leacock) when Dirk plays the titular role of a man a boy (Whitlely) turns to when neglected by his own father.)

We also briefly discussed the film’s two main female characters, although they play small roles. It is understandable that we would partly judge Christopher by his wife Magda (Elizabeth Sellars) – the woman with whom he has fallen in love and chosen to spend his life. Magda does not receive much screen time, her infidelity mostly providing the reason for Christopher’s actions. The greater focus given to the film’s other characters is even shown in her introduction. Her first appearance is obscured when she is seen from Robbie’s point of view as he hides under her and Christopher’s bed.

Although Magda admits she has been unfaithful to Christopher, she remains loyal in her own way. When Christopher breaks into the flat at night and clamps his hand over her mouth, and strikes her in anger, she soon recovers.

Although Magda admits she has been unfaithful to Christopher, she remains loyal in her own way. When Christopher breaks into the flat at night and clamps his hand over her mouth, and strikes her in anger, she soon recovers.  She also does not seem to have been affected by the death of her lover. In fact, she tries to seduce Christopher. Even after she has been rejected by Christopher (he dismisses her offer of jewellery to him) she is unhelpful to the police.

She also does not seem to have been affected by the death of her lover. In fact, she tries to seduce Christopher. Even after she has been rejected by Christopher (he dismisses her offer of jewellery to him) she is unhelpful to the police.

Mrs Sykes (Kay Walsh), the landlady of the B & B in the North of England at which Christopher and Robbie stay, contrasts to Magda. Magda’s expensive clothes provoke comment from the sharp-eyed police as to her fidelity (it is assumed she has received money or gifts from her lover, providing Christopher with a motive for the murder) and she is wearing a glamorous nightgown when Christopher breaks into the flat. Mrs Sykes is coded as working class through her garments – she wears a floral apron to protect her clothes as she does her housework. Mrs Sykes’ concern for Robbie, and her brave defence of him (she is worried that Christopher will harm the boy) is also an antidote to Robbie’s parents, the Campbells (Jack Stewart and Jane Aird), who appear to hold a similar social status. Mrs Sykes insists that Robbie takes a bath, and this leads to the revelation of his abuse at the hands of his parents – he bears the marks of a severe lashing.

Mrs Sykes (Kay Walsh), the landlady of the B & B in the North of England at which Christopher and Robbie stay, contrasts to Magda. Magda’s expensive clothes provoke comment from the sharp-eyed police as to her fidelity (it is assumed she has received money or gifts from her lover, providing Christopher with a motive for the murder) and she is wearing a glamorous nightgown when Christopher breaks into the flat. Mrs Sykes is coded as working class through her garments – she wears a floral apron to protect her clothes as she does her housework. Mrs Sykes’ concern for Robbie, and her brave defence of him (she is worried that Christopher will harm the boy) is also an antidote to Robbie’s parents, the Campbells (Jack Stewart and Jane Aird), who appear to hold a similar social status. Mrs Sykes insists that Robbie takes a bath, and this leads to the revelation of his abuse at the hands of his parents – he bears the marks of a severe lashing.

The police’s interaction with the parents is also telling. The parents insist that they are not Robbie’s ‘real’ parents since he is adopted. Through the police’s questioning it soon becomes clear that he has few toys. The fact that the police have such insight (despite their bungling pursuit of Christopher) suggests that they often come into contact with such cases of abuse. The film’s establishing of its post war setting through its lingering of bombed-out buildings implies that in post-war Britain society’s most vulnerable victims are being overlooked.

The police’s interaction with the parents is also telling. The parents insist that they are not Robbie’s ‘real’ parents since he is adopted. Through the police’s questioning it soon becomes clear that he has few toys. The fact that the police have such insight (despite their bungling pursuit of Christopher) suggests that they often come into contact with such cases of abuse. The film’s establishing of its post war setting through its lingering of bombed-out buildings implies that in post-war Britain society’s most vulnerable victims are being overlooked.

As ever, do log in to comment, or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk and let me know if you’d like me to add your thoughts.