Posted by Sarah

It would be useful to draw together some of our group’s activities and discussion on melodrama over the last 9 months. I’ve added my own thoughts below which ended up being far more fulsome than originally intended!), but do log in to comment or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk to include your ideas. It would be great if people provided their own overviews, or a detailed focus on an element (such as the definition of melodrama or a specific film) which especially interested them.

We were very fortunate to begin the academic year with a Research Seminar at which Birmingham School of Media’s Dr John Mercer (co-author, with Martin Shingler, of Melodrama: Genre, Style, Sensibility, 2004) presented. John’s talk ‘Acting and Behaving Like a Man: Rock Hudson’s Performance Style’ focused on Hudson’s ‘behaving’ in several Douglas Sirk melodramas: Magnificent Obsession (1954), All That Heaven Allows (1955) and Written on the Wind (1956). This provided us with some great insights into probably the most referenced Hollywood director of film melodramas as well as underlining the close relationship between melodrama and performance.

We were very fortunate to begin the academic year with a Research Seminar at which Birmingham School of Media’s Dr John Mercer (co-author, with Martin Shingler, of Melodrama: Genre, Style, Sensibility, 2004) presented. John’s talk ‘Acting and Behaving Like a Man: Rock Hudson’s Performance Style’ focused on Hudson’s ‘behaving’ in several Douglas Sirk melodramas: Magnificent Obsession (1954), All That Heaven Allows (1955) and Written on the Wind (1956). This provided us with some great insights into probably the most referenced Hollywood director of film melodramas as well as underlining the close relationship between melodrama and performance.

Nottingham Trent University’s Dr Gary Needham also presented at a fascinating Research Seminar. In ‘Revisiting Tea and Sympathy (1956): Minnelli, Hollywood, Homosexuality’. Gary, like John, explored the work of specific Hollywood director associated with melodrama: in this case Vincente Minnelli. Gary’s work interestingly opened up debate on gender relations and sexuality with a sensitive re-reading of Minnelli’s Tea and Sympathy.

In our fortnightly meetings since January we have broadened out from this focus on 1950s Hollywood melodrama. We have screened a surprisingly wide variety of films with connections to melodrama, which hailed from France, Britain, the US, and Hong Kong and stretched from the silent cinema of the 1900s to contemporary film of the 2000s. We have also organised a very enjoyable and useful read through of a play.

We started with debate on the male melodrama by referencing Steve Neale’s reconsideration of melodrama in ‘Melo Talk’. Neale argued that unlike the 1970s  feminists who wrote on melodrama in relation to the ‘women’s film’, trade press from Hollywood’s Studio Era was more likely to attach the term ‘melodrama’ to films with male-focused themes, such as film noir. Viewing Richard Fleischer’s The Narrow Margin (1952) which was hailed at its time of release as a ‘Suspense Melodrama’ allowed us to engage with Neale’s argument in a practical as well as theoretical way.

feminists who wrote on melodrama in relation to the ‘women’s film’, trade press from Hollywood’s Studio Era was more likely to attach the term ‘melodrama’ to films with male-focused themes, such as film noir. Viewing Richard Fleischer’s The Narrow Margin (1952) which was hailed at its time of release as a ‘Suspense Melodrama’ allowed us to engage with Neale’s argument in a practical as well as theoretical way.

But melodrama is more usually thought of as being related to suffering. The American Film Institute defines melodramas as ‘fictional films that revolve around suffering protagonists victimized by situations or events related to social distinctions, family and/or sexuality, emphasizing emotion’. (http://afi.chadwyck.com/about/genre.htm). In keeping with this, we screened George Melford’s The Sheik (1921). The Sheik and the next film, Robert Z. Leonard’s The

But melodrama is more usually thought of as being related to suffering. The American Film Institute defines melodramas as ‘fictional films that revolve around suffering protagonists victimized by situations or events related to social distinctions, family and/or sexuality, emphasizing emotion’. (http://afi.chadwyck.com/about/genre.htm). In keeping with this, we screened George Melford’s The Sheik (1921). The Sheik and the next film, Robert Z. Leonard’s The  Divorcee (1930), were more closely related to traditional notions of melodrama focused on by feminists in the 1970s. Both of these centred on melodramatic plots and had suffering women at their hearts. Though the earlier film presented events in a more melodramatic way, partly due to the type of acting which is thought to predominate in the silent era.

Divorcee (1930), were more closely related to traditional notions of melodrama focused on by feminists in the 1970s. Both of these centred on melodramatic plots and had suffering women at their hearts. Though the earlier film presented events in a more melodramatic way, partly due to the type of acting which is thought to predominate in the silent era.

Our screening of Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1938) opened out our discussion to animation. Once more the melodramatic plot was in place, though we did note that the use of comedy tempered the melodramatic elements.

Showing two versions of Gaslight – the British film directed

Showing two versions of Gaslight – the British film directed by Thorold Dickinson in 1940 and the Hollywood remake helmed by Gorge Cukor in 1944 – allowed us to compare examples from two major film industries. In terms of melodrama the same, or at least a similar, story being told in different ways was especially illuminating. The plot underpinning both is melodramatic, but the polished approach of Hollywood was strikingly different to the ‘blood and thunder’ uppermost in Dickinson’s film. The Gothic subgenre of these films also provided much discussion.

by Thorold Dickinson in 1940 and the Hollywood remake helmed by Gorge Cukor in 1944 – allowed us to compare examples from two major film industries. In terms of melodrama the same, or at least a similar, story being told in different ways was especially illuminating. The plot underpinning both is melodramatic, but the polished approach of Hollywood was strikingly different to the ‘blood and thunder’ uppermost in Dickinson’s film. The Gothic subgenre of these films also provided much discussion.

Weekly activities in the Summer Term provided us with scope to show more, and some longer, films. We began with John Baxter’s Love on the Dole (1941) which fascinatingly combined a melodramatic plot with the aesthetics of social realism. Its unusual, downbeat, approach was highlighted by the films we screened the following week: George Melies’ Barbe-Bleu (1901), D.W. Griffiths’ The Mothering Heart (1913) and Lois Weber’s

Weekly activities in the Summer Term provided us with scope to show more, and some longer, films. We began with John Baxter’s Love on the Dole (1941) which fascinatingly combined a melodramatic plot with the aesthetics of social realism. Its unusual, downbeat, approach was highlighted by the films we screened the following week: George Melies’ Barbe-Bleu (1901), D.W. Griffiths’ The Mothering Heart (1913) and Lois Weber’s  Suspense (1913). Showing some very early short melodramas by French and American film pioneers George enabled us to directly compare films from cinema’s earlier days, afforded us the opportunity of watching the work of a female director which seems apt given melodrama’s usual focus on the female, and provoked thoughts regarding the use of suspense and restraint.

Suspense (1913). Showing some very early short melodramas by French and American film pioneers George enabled us to directly compare films from cinema’s earlier days, afforded us the opportunity of watching the work of a female director which seems apt given melodrama’s usual focus on the female, and provoked thoughts regarding the use of suspense and restraint.

The screening of Tobe Hooper’s Poltergeist (1982) turned the group’s attention to horror. This provided us with an opportunity to assess the way melodrama works with, and amongst, other related genres. Wong Kar Wai’s Happy

The screening of Tobe Hooper’s Poltergeist (1982) turned the group’s attention to horror. This provided us with an opportunity to assess the way melodrama works with, and amongst, other related genres. Wong Kar Wai’s Happy  Together (1997) proved to be another surprising, but interesting choice for discussion. The clearly melodramatic plot concerning two young lovers’ trials was presented, at times, in a documentary style. This was thought to be revealing of melodrama’s inherent variety.

Together (1997) proved to be another surprising, but interesting choice for discussion. The clearly melodramatic plot concerning two young lovers’ trials was presented, at times, in a documentary style. This was thought to be revealing of melodrama’s inherent variety.

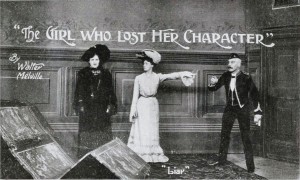

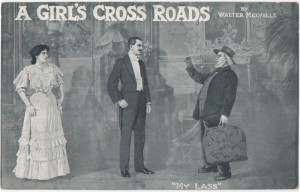

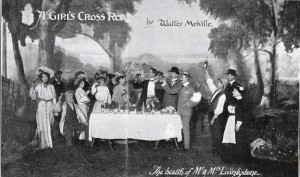

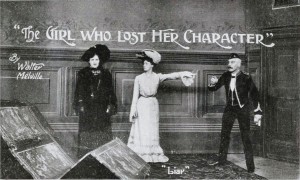

A read-through of Frederick and Walter Melville’s 1903 play A Girl’s Cross Roads returned us to more traditional notions of melodrama. The plot and the performances (at least when ‘performed’ by us!) were certainly over the top, with suffering central to the play.

Our most recent screening of David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive (2001) proved very useful as it was a thoughtful meditation on melodrama especially in its parodying of the genre and Hollywood films of the 1950s.

In addition to our screenings and the read through we have been contacted by the BFI who are staging an event about melodrama in 2015. They intend to screen 50 unmissable melodramas. We compiled our own list of 50 unmissable melodramas (http://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2013/03/03/the-bfi-and-50-unmissable-melodramas/) which we had reduced from the longer list of 225 titles (http://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2013/03/03/unmissable-melodramas-the-long-list/) We are currently working through (and adding to!) these. We also plan to widen out further from film melodrama by engaging with theatre, television and radio(see the next post on Summer Activities for more information).

The Melodrama Research Group is busy working on several events: a screening of Midnight Lace (1960) in September, a forthcoming Symposium, a Festival, a Trip and is looking into Publishing Opportunities.