Posted by Sarah

Due to the length of the film, discussion was fairly short but it included: the theme of performance and imitation in melodrama and What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?; Bette Davis and Joan Crawford’s performances in the film; comparison to other Davis and Crawford films and performances; the intended Davis/Crawford follow-up film Hush… Hush, Sweet Charlotte; some specific memorable scenes; the off-screen melodrama of Bette and Joan’s ‘feud’ and the daughters’ autobiographies.

The centrality of performance to melodrama generally (which we have been focusing on particularly in the last few weeks), and to this film specifically, was noted. Of course, in part this is due to the fact both screen stars play characters who were once actresses. The film’s skilful use of old screen clips of Davis and Crawford’s films to demonstrate this was striking, especially when juxtaposed to their current, older images. We noted that this also occurred with Gloria Swanson in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950) and was mentioned in some of this week’s readings (see Brooks, Morey etc) In both films it drives home their central

The centrality of performance to melodrama generally (which we have been focusing on particularly in the last few weeks), and to this film specifically, was noted. Of course, in part this is due to the fact both screen stars play characters who were once actresses. The film’s skilful use of old screen clips of Davis and Crawford’s films to demonstrate this was striking, especially when juxtaposed to their current, older images. We noted that this also occurred with Gloria Swanson in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950) and was mentioned in some of this week’s readings (see Brooks, Morey etc) In both films it drives home their central  theme of performance. The older ‘Baby’ Jane (played by Davis) performs several times in the film by enacting her old song and dance routine. The film highlights these moments by the staging: a ceiling light acts as a spotlight and Jane/Davis faces front.

theme of performance. The older ‘Baby’ Jane (played by Davis) performs several times in the film by enacting her old song and dance routine. The film highlights these moments by the staging: a ceiling light acts as a spotlight and Jane/Davis faces front.

The theme of Jane performing also plays out as she imitates her sister Blanche. Jane does so mockingly to begin with as she throws a phrase Blanche has just uttered back in her face, but later her imitation is used for the purpose of impersonation. The first time this occurs it is relatively innocent. Alcoholic Jane is annoyed that Blanche has cancelled her account with the local off-license and she successfully fools them into believing they are talking to Blanche on the telephone. Not only does she uncannily imitate Blanche’s voice, but she also, arguably unnecessarily, uses similar facial  expressions. The second occurrence is far more sinister. Wheelchair-bound Blanche has struggled downstairs and telephoned for help. Once more, Jane manages to convince the person she is talking to (a Doctor in this case) that she is in fact Blanche. Blanche is therefore denied the held she so desperately requires, and struggled so hard to gain access to.

expressions. The second occurrence is far more sinister. Wheelchair-bound Blanche has struggled downstairs and telephoned for help. Once more, Jane manages to convince the person she is talking to (a Doctor in this case) that she is in fact Blanche. Blanche is therefore denied the held she so desperately requires, and struggled so hard to gain access to.

We discussed the way in which Davis effectively portrayed Jane’s switch between the performance of childlikeness (her admittedly deluded, but still slightly detached, enactment of her old song and dance routine) and her regression to childhood. This appeared to be triggered by the cleaner Elvira finding that Jane was keeping Blanche tied up and locked in her room. After attacking and killing Elvira with a hammer, Jane pleads with Blanche to advise her. This is in stark contrast to the control she previously exercised over her sister. Later still, when Jane is concerned with escape, her first thought is to travel to the beach with Blanche. It was noted that both Rain (1932) and Baby Jane end with deaths on beaches: in Rain the reformer Davidson (Walter Huston) commits suicide there, while in Baby Jane Blanche dies due to her sister’s neglect and abuse. We thought this was especially interesting since the beach has been written of as a place of safety,  given its relation to childhood, and as a female space. Jane’s delight in obtaining (though significantly not purchasing) ice-creams for herself and Blanche and Davis’ uninhibited performance of Jane’s impromptu old song and dance routine on the beach underlines her regression.

given its relation to childhood, and as a female space. Jane’s delight in obtaining (though significantly not purchasing) ice-creams for herself and Blanche and Davis’ uninhibited performance of Jane’s impromptu old song and dance routine on the beach underlines her regression.

Davis’ use of gestures was also  commented on. Many of these are in the service of revealing Jane’s true self – whether as unbalanced tormentor or a frightened child. We might particularly think of the most exaggerated: the relish with which she kicks the helpless Blanche. This was also true of the most exaggerated gestures Davis employed in Of Human Bondage (1934). These occurred during Mildred’s tirade against Philip (Leslie Howard) and

commented on. Many of these are in the service of revealing Jane’s true self – whether as unbalanced tormentor or a frightened child. We might particularly think of the most exaggerated: the relish with which she kicks the helpless Blanche. This was also true of the most exaggerated gestures Davis employed in Of Human Bondage (1934). These occurred during Mildred’s tirade against Philip (Leslie Howard) and effectively revealed her violent and ugly character. A difference between the characters – Mildred is always performing in some sense while Jane occasionally performs her old song and dance routine – is marked, however. It was also noted that the only way for Davis to successfully play a mentally unbalanced character regressing into childhood was to overplay her.

effectively revealed her violent and ugly character. A difference between the characters – Mildred is always performing in some sense while Jane occasionally performs her old song and dance routine – is marked, however. It was also noted that the only way for Davis to successfully play a mentally unbalanced character regressing into childhood was to overplay her.

There is a further, more subtle level of character performance: the way we all display certain aspects of our character at different times and in varying situations in everyday life. This is less applicable to Davis’ Jane as on the whole she does not appear to be putting on an act: she mostly tells her neighbours, the cleaner Elvira and especially her sister Blanche, exactly what she thinks. Even the insidious way in which Jane causes Blanche to fear eating the meals Jane prepares is due to Jane’s previous grand gestures: the serving up of Blanche’s pet budgerigar and later a rat for dinner.

Crawford has fewer opportunities than Davis to signal her performance. However, she must often placate the mentally unstable Jane by being less than truthful. Crawford does still have some moments which require extreme reaction. She becomes increasingly persecuted by Jane and fearful of the meals her sister serves. A particularly noteworthy sequence involves both stars. Blanche/Crawford’s scream of horror as she uncovers the

Crawford has fewer opportunities than Davis to signal her performance. However, she must often placate the mentally unstable Jane by being less than truthful. Crawford does still have some moments which require extreme reaction. She becomes increasingly persecuted by Jane and fearful of the meals her sister serves. A particularly noteworthy sequence involves both stars. Blanche/Crawford’s scream of horror as she uncovers the  garnished dead rat is followed by Jane/Davis’ hysterical laugher. Jane has waited outside to hear Blanche’s reaction and the juxtaposition of shots and similar sounds effective unites the sisters and the stars. Crawford’s shifting between restraint and a certain level of exaggeration (her fear) was compared to her earlier performance in Rain (1932).

garnished dead rat is followed by Jane/Davis’ hysterical laugher. Jane has waited outside to hear Blanche’s reaction and the juxtaposition of shots and similar sounds effective unites the sisters and the stars. Crawford’s shifting between restraint and a certain level of exaggeration (her fear) was compared to her earlier performance in Rain (1932).

The theme of performance extends to other characters in the film. Pianist Edwin Flag (played by Victor Buono) is first seen at home with his mother, Dehlia, (played by Marjorie Bennet) when she telephones Jane pretending to be her son’s secretary. When Edwin visits Jane he ‘performs’ literally since he accompanies Jane’s singing on the piano. Performance is also present as he displays a particular side of himself to Jane in the hope that she will employ him. He plays up his Englishness and emphasises his claims to refinement when the two take tea together. Most notable is Edwin’s response to Jane’s routine. He does well to hide his horror at her attempts to sing. Edwin declares that Jane’s act is ‘wonderful’ when the camera’s privileged view of his face suggests he believes precisely the opposite. The audience must, of course, agree with this opinion. While Edwin is forced to listen and watch Jane through his need for paid employment, we find it hard to tear our eyes and ears away from the fascinating and grotesque spectacle: of both Jane and Davis.

the piano. Performance is also present as he displays a particular side of himself to Jane in the hope that she will employ him. He plays up his Englishness and emphasises his claims to refinement when the two take tea together. Most notable is Edwin’s response to Jane’s routine. He does well to hide his horror at her attempts to sing. Edwin declares that Jane’s act is ‘wonderful’ when the camera’s privileged view of his face suggests he believes precisely the opposite. The audience must, of course, agree with this opinion. While Edwin is forced to listen and watch Jane through his need for paid employment, we find it hard to tear our eyes and ears away from the fascinating and grotesque spectacle: of both Jane and Davis.

We also briefly discussed the film’s style. The film often cross-cuts between Jane returning home in her car after running some errands and Blanche’s futile attempts at escape. In addition, Aldrich often signposts the particularly heightened moments of melodrama with an overtly dramatic use of shot choice (notably the zoom) and sound (often non-diegetic music).The scene in which an increasingly frustrated Blanche ineffectually wheels her chair around on the spot is a good example. In order to drive home Blanche’s feelings of confinement, Aldrich switches from a straight-on to an overhead camera angle which better reveals her inability to move far. Another very memorable shot is the one which prompts Jane to break down on the staircase. This depicts Edwin/Buono wheeling a wheelchair through the hall with a blanket over his head and a Baby Jane doll on his lap. In addition to causing Jane to react, it is puzzlingly bizarre in itself, and manages to be conspicuous in a film full of odd moments.

The intended Crawford and Davis follow-up to Baby Jane: Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964) also prompted some fruitful reflection. In this the roles of tormentor and tormented as played out in Baby Jane by Davis and Crawford respectively, were meant to be reversed. Before Crawford pulled out and was replaced by Olivia de Havilland, she was set to play Miriam – Charlotte’s (Davis) tormentor. Interestingly the American Film Institute (AFI) defines Hush…Hush as horror rather than melodrama. Though it is certainly true that the boundary between the two is blurred and that Baby Jane itself has elements of horror. (We will be able to explore this more over the next two weeks as we focus on the horror genre.) Baby Jane and Hush…Hush contain other notable similarities. In addition to the planned reteaming of Davis and Crawford another star of Baby Jane appears: Buono intriguingly plays Charlotte’s father in Hush….Hush’s  flashbacks. At the character level we observed the fate of the cleaner/housekeeper in both films. In Baby Jane Blanche’s ally, and cleaner, Elvira (Maidie Norman), is killed by Jane while Velma (Agnes Moorehead) Charlotte’s housekeeper and friend in Hush…Hush… suffers a similar fate.

flashbacks. At the character level we observed the fate of the cleaner/housekeeper in both films. In Baby Jane Blanche’s ally, and cleaner, Elvira (Maidie Norman), is killed by Jane while Velma (Agnes Moorehead) Charlotte’s housekeeper and friend in Hush…Hush… suffers a similar fate.

Of course the off-screen melodrama of Crawford and Davis’ ‘feud’ and their personal difficulties were also a point of discussion. Both Crawford and Davis’ daughters (the latter’s offspring, BD Hyman, played the young neighbour in Baby Jane) wrote autobiographies which contained less than flattering portraits of their mothers. Christina Crawford waited until her mother had died to publish her account, and therefore Joan could not put across her point of view. Davis noted how unfair this was and when Davis’ own daughter published a similar volume Davis was able to retaliate to the accusations in her own memoir This ‘n That.

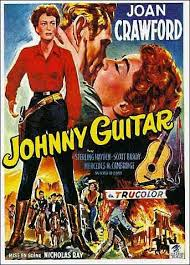

We ended the session with a brief reference to Davis and especially Crawford in relation to camp. The 60-something Crawford temporarily taking over her ill 20-something daughter’s role in a TV soap is a very good example, while Crawford’s 1954 film Johnny Guitar is notorious for its status as a camp classic. In Nicholas Ray’s film, Crawford feuded on and off-screen with another actress– this time Mercedes McCambridge. We thought it noteworthy that the clip from comedy series Psyhcobitches privileged the notion of camp. It certainly seems that camp, specifically in relation to Baby Jane, is closely attached to Davis and Crawford’s star images in retrospect.

relation to camp. The 60-something Crawford temporarily taking over her ill 20-something daughter’s role in a TV soap is a very good example, while Crawford’s 1954 film Johnny Guitar is notorious for its status as a camp classic. In Nicholas Ray’s film, Crawford feuded on and off-screen with another actress– this time Mercedes McCambridge. We thought it noteworthy that the clip from comedy series Psyhcobitches privileged the notion of camp. It certainly seems that camp, specifically in relation to Baby Jane, is closely attached to Davis and Crawford’s star images in retrospect.

Many thanks to Lies and Ann-Marie for sharing their extensive Joan and Bette knowledge and providing some great competition prizes!

Do, as ever, log in to comment or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk to add your own thoughts.