An earlier version of this was first posted on 30th April 2012

Is management by fact a bit simplistic?

What about the emotional aspects of work; trust, appreciation, excitement, fear, worry, concern?

How can these things be properly addressed? A lot of these things will be more or less important depending on how we see the world. And each of us see the world differently to everyone else!

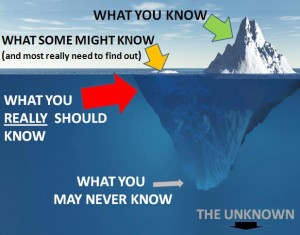

If we want to improve anything it is best to devise those improvements from a perspective of understanding, in other words by using knowledge. Unfortunately we live in a world of incomplete knowledge and, dare I say it, differing perceptions (we all see things differently). Deming suggests that we work on the basis of a decent theory of knowledge – but what does he mean? Consider the iceberg analogy:

* A start point is to understand that there are things that most of us know and are obvious, like the peak of an iceberg.

* A start point is to understand that there are things that most of us know and are obvious, like the peak of an iceberg.

*Next there are the flatter ice floes, which a good ‘spotter’ on a ship might notice bobbing in the waterline. It is important that we know about these and we should get better at spotting them.

* However there is also sub-surface ice (in this analogy) – those things not visible to anyone and for which we need to delve into or at least give consideration. These insights might include decent ‘hunches’ – or ‘beliefs’ – or ‘theory’ – or experience). Effort in these instances is needed either to seek better knowledge or at least think properly about how we might have to deal with them. If we blindly sail through areas were sub-surface ice may be lurking (and assume that what we don’t know will not hurt us) we would be a little foolish.

* There is also stuff that we don’t know … and need never know… it is out of our sphere of influence and we cannot do much to manage it – in these cases – don’t worry.

* Deepest of all is the ‘unknown’ – that which we will never know – (so again don’t worry)

In summary we should seek reasonable knowledge when we make decisions; we should not ignore things which are too difficult to understand and we should be honest when we are making assumptions. If we do this, then the outcomes of change, whether good or bad, will be better understood and will help to inform us in the future. If we need to broach sensitive subjects: trust, appreciation, excitement, fear, worry, concern, then a conversation is a good start point.

More reading:

Covey, S. (1989) 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, Simon & Shuster, New York, NY.

Deming W.E. (1982) Out of the Crisis, MIT CAES, Cambridge MA.