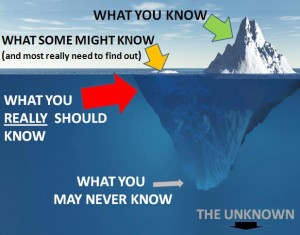

Like it or not, our brains are biologically structured to process information in two distinct ways (more actually, but we will focus on two here). On one hand we can process huge amounts of routine, familiar information, whilst on the other hand we are also adept at processing novel information.

Having a brain that can quickly process vast amounts of routine information is very helpful; it allows us to work on auto-pilot when we want to think about other things. If we step out from a dark hallway onto a busy, sunlit street, we do not feel overloaded with information. Instead we fit what we see, hear and smell into our mental models (‘paradigms’ in the technical jargon) and filter the information to best understand what is happening and where we are – and we go about our business of the day.

Much as this might be a strength, it can also be a hindrance. Even the predators of human prehistory adapted successful strategies to exploit this weakness. The crouching tiger hidden in the bushes can easily remain unseen to the unsuspecting passer-by until it is too late…

Fortunately we are not simply data-processors; the architecture of our brain provides other capabilities. If we perceive something unfamiliar, such as the backfire of a car engine, we notice it. If a carnival procession turns into the street we notice it. We adapt both our expectations and our behaviour. If movement is noticed in the bushes we ready ourselves for fight or flight – let’s hope it is not a tiger!

Learning works on this counter-intuitive level. John Seddon often talks about revealing counter-intuitive truths to open people’s minds to change. Neuroscience describes this as ‘cognitive dissonance’; stopping our mind from processing automatically and setting us up to restructure our thinking.

Charles Jacobs (2009) suggests that change is as much about re-structuring thinking as it is changing things like IT systems, team members, job descriptions, terms and conditions, performance measures or budgets. The latter are all methods which , although familiar ‘instruments of change’, are misunderstood or poorly executed. Furthermore just implementing new ‘stuff’ can be observed by somewhat cynically by employees as either management tinkering or a lame or half-baked compromise. The result is little or no lasting change.

A game-changing approach is more effective. Jacobs’ describes how Mahatma Gandhi chose to meet violence with non-violence, breaking the cycle of escalation and opening a different dialogue for change.

In managing change, we need to take more account of what needs to be done to change people’s minds. According to Jacobs, to “stop the way people are thinking now and create a new way of thinking that will drive the behaviour we need to achieve the future…”

Further Reading:

Deming W.E. (1993) The New Economics, MIT CAES, Cambridge MA.

Jacobs, C.J. (2009) Management Rewired: Why Feedback Doesn’t Work and Other Surprising Lessons from the Latest Brain Science, Penguin Group Portfolio, NY

Seddon, J. (2005) Freedom from Command and Control, Vanguard Press, Buckingham, UK.

My son and I have been monitoring the frogspawn in our garden pond since April. It has been fascinating to see the tadpoles hatch, then grow into monstrous alien-looking aquatic denizens. Suddenly in the last couple of weeks they have started sprouting limbs, then their feet and toes have lengthened becoming mobile. Body shapes change, the tails shorten and a new form develops.

My son and I have been monitoring the frogspawn in our garden pond since April. It has been fascinating to see the tadpoles hatch, then grow into monstrous alien-looking aquatic denizens. Suddenly in the last couple of weeks they have started sprouting limbs, then their feet and toes have lengthened becoming mobile. Body shapes change, the tails shorten and a new form develops.