Following on from my earlier Melvillodrama post, we have one brief typescript reminiscence of Walter Melville of the dangers of weapons on stage which I’m desperate to share (0599807/19). I often get this out for seminars, but I think most people don’t get around to reading it, which is a shame because it shows all the trademark humour and eccentricity of the Melville family.

‘A Melodrama would be lost without a scene in which a dagger, revolver or gun is used’, according to Walter. In order to legally use a weapon on stage, a licence had to be granted; in one case, Walter ran up against problems due to the fact that a named person had to be granted the right to carry a revolver. Since Walter himself was not playing the part, and could not be sure that the same actor would be in that role on every night, the imaginative ‘…Inspector of police…decided to grant a licence…in the fictitious name of the villain in the play. Thus a non existing person possessed a licence to carry a revolver’.

Discussing the dangers of weapons on stage, Walter relates the tale of a faulty prop, which, unknown to the Property man ‘continually misfired’ and so was

‘loaded…until the charges came to the mouth of the barrel. This gun…exploded with wonderful effect – it put out every gas light in the Theatre.’

Although it seems a fitting drama for a melodrama, you wonder whether the people nearby thought it was a wonderful effect!

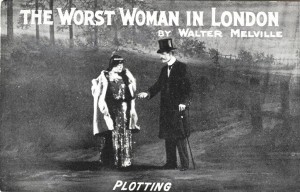

Disasters with weapons didn’t always involve blood or explosions, however. During an 1899 production of ‘The Worst Woman in London’, the gun with which the villianess was supposed to kill her elderly husband failed to go off,

‘…and the man in the wings who is supposed to safeguard this happening, for some reason of another did not fire the deputy shot. The Villainess realising the old man’s death was desirable for the good of the Show, crossed to the bedside and stabbed him with the end of the revolver. The old gentleman seemed perfectly satisfied with the change in the method of his murder and spoke his usual line – “I am shot”.’

Walter’s story of how he came to be in possession of a revolver of his own is a real-life melodrama;

An acquaintance of mine, not in the Theatrical business, got himself into some difficulties and decided that the only way out of the scrape was to shoot himself. He came along to my office and making up his mind very suddenly – he pulled out this revolver, fully loaded, and said to me – “Goodbye Walter” Acting on the spur of the moment, I brought my fist into play and knocked the revolver out of his hand, telling him that if he claimed to be a friend of mine not to do this dirty business in my office, but to go into the Street and do whatever he liked to himself there.

Of course, the others of the Melville family seem just as unusual as Walter. Walter once mentioned to his ‘Brother’ (presumably wither Fred or Andrew II) the necessity of having a licence for his firearms, pointing out that he had none and owned ‘100 rifles, 30 revolvers and 3 machine guns’, a sizable arsenal for a theatre manager. When this brother finally asked for a licence, in a provincial town,

‘the Inspector told him he was only in the position to licence one article and as he was in possession of an armoury, he had better get out of the office and do what he liked in the matter’.

I look forward to discovering more of the dramatic life and times of the Melvilles as I continue to get out parts of the collection for researchers!