So here is the summer, or what counts for it in Britain, anyway. Are you planning your holidays, looking forward to reading a good book on a long sandy beach, exploring new places or simply relaxing by the pool? Or are you stuck at your desk, wondering whether the sunshine is going to last? Well, wherever you are, spare a thought for the tourist of the early nineteenth century, for whom just crossing the Channel was a three hour voyage.

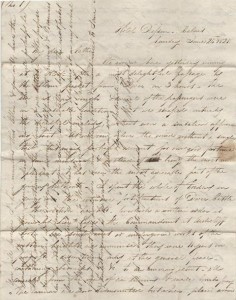

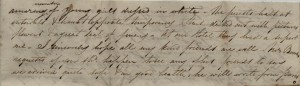

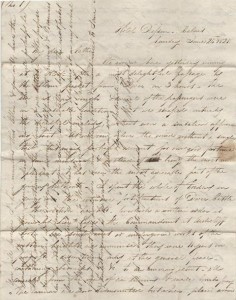

We’ve recently been lucky enough to have a volunteer who willingly trawled through a deed box containing nineteenth century papers, known by the mysterious name of ‘The Hansard Family Deed Boxes’. Among the assorted gems contained within are a series of letters written in 1821 by William Harris to his father (another William Harris) in London, while he toured around Europe. There are around a dozen letters extant in this  collection, many tightly written and over-written, with William junior filling up every available space on the paper. So even if you’re not off anywhere this summer, join us for an adventure across Europe, nineteenth-century style!

collection, many tightly written and over-written, with William junior filling up every available space on the paper. So even if you’re not off anywhere this summer, join us for an adventure across Europe, nineteenth-century style!

William’s first letter is a sort of extended postcard, in which he details his journey from Dover to Calais with the breathless excitement of an enthusiastic explorer. At Dover, William (Junr.) took in the castle, the ‘souterrains’ or tunnels and the western heights. The castle he found rather underwhelming, “contains nothing admirable in point of architecture”, but he was evidently fascinated by the “many excellent contrivances for… defence” in the tunnels. These he described as “immense”, adding:

they were 11 years in [use] and discontinued only at the general peace – containing barracks etc. etc. to an amazing extent – all concealed from the view of an enemy and made bomb proof.

The Napoleonic Wars had ended only 6 years prior to his visit, when space had been needed for 2000 extra soldiers and supplies to guard the port. To date, these tunnels at Dover remain the only underground barracks in Britain.

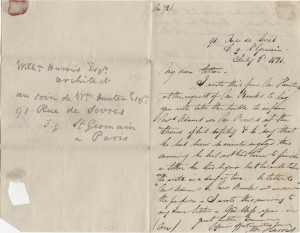

The first page of William’s letter

In Dover, William met his friend Mr. Brooks, who had persuaded his friend Mr. I Winckworth to accompany them to Boulogne. William told his father, “this is very fortunate for us – Mr. W. having visited France before”. Despite being new to the cross-channel voyage, William described it as “a most delightful passage”, he and his friends having escaped the “dreadful malady” which most of the other passengers suffered. At Calais, he related how the three men and their baggage had been searched at the Customs House for any “contraband merchandise”, and their passports had been exchanged for temporary documents. He explained: “The passport obtained in England will be forwarded on and meet us again at Paris.”

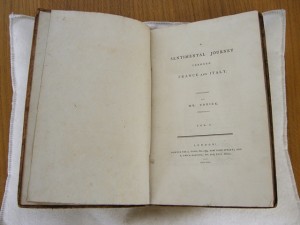

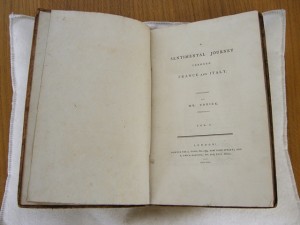

Although they had hoped to stay at Meurice’s Hotel, they group ended up lodging at the Hotel Dessin, immortalised in Lawrence Sterne’s A Sentimental Journey through France and Italy. Sterne (under the pseudonym Mr. Yorick) undertook this journey in 1765, although the book was not published until he was on his deathbed. Perhaps more famous than this was Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, yet Sterne’s travel piece helped to established the genre of travel writing and emphasised the importance of the personal, or sentimental, point of view. William noted “his name is written on the door of the chamber he occupied” – an early example of celebrity culture!

Title page of Sterne’s ‘A Sentimental Journey’, 1768

We occupy three apartments on the ground floor looking into an open court laid out as a flower garden – quite out of the noise of the street – the only approach to it being through the outer court into which the carriages enter under an archway – this I am told is the usual style[?] of a French Hotel – the garden is ornamented with statues and vases.

William Harris Junr., June 24 1821

William was evidently concerned at the level of Englishness which the foreign metropolis of Calais might provide. In the event, he was relieved to find that the town “presents a great many English characteristics”, and commented that his hotel had “adopted many good English customs”. One thing which was less familiar, however, was the Fête de Dieu, known in England as Corpus Christi, the Catholic celebration of the Eucharist. William wrote “there is to be a grand procession here at 11 o’clock this morning”, then resumed his letter at midday to describe the events to his father:

We have just witnessed the procession of the Fête de Dieu. The streets are hung with…carpets and white linen. The pavements thrown with rushes and a few flowers – white flags are suspended from the windows which are filled with well dressed women. A company of ‘Pompiers’ or Fire men who wear a military costume precede the procession with a band which is followed by priests with a portable canopy for the…principle and an amazing number of girls dressed in white. The priests halt at intervals and chaunt opposite temporary altars decked out with pictures, flowers and a great deal of finery. At our Hotel they had a superb one.

Following this excitement, William had little to comment upon but the weather, which he advised was “much the same as in England.”

Following this excitement, William had little to comment upon but the weather, which he advised was “much the same as in England.”

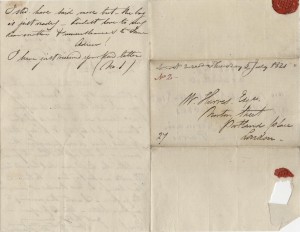

The group planned to travel to Paris via Boulogne, Amiens and Beauvais; William advised his father to write to him at Paris, addressing his letters to “William Harris, Architect, Paris”; apparently architects were few and far between in the capital! With a sensible logic, William numbered his letter ‘1’ and asked his father to do the same with each one he sent, so that they could both work out which had been sent first if they all arrived at once.

Ending his letter with love to his mother and sister, kindest regards to Mr. Evans and “compliments to enquiring friends”, William intended to send his letter via first mail to England the following day. Since it is included in this small collection, we can assume that it reached its intended destination.

This one letter can tell us so much about nineteenth century attitudes towards travel, realities of tourism and the differences between France and England. But as much as anything if, like me, you like to do some armchair travelling, then these accounts provide an intriguing account of taking a holiday nearly 200 years ago.

This one letter can tell us so much about nineteenth century attitudes towards travel, realities of tourism and the differences between France and England. But as much as anything if, like me, you like to do some armchair travelling, then these accounts provide an intriguing account of taking a holiday nearly 200 years ago.

And what happened next? Keep checking the blog to find out!

You can see William’s letter, a copy of A Sentimental Journey and some other travelling treasures on display in the Templeman Library foyer – but only for a limited time.

I’d like to say a special thank you to Marjolijn Verbrugge for her enthusiastic hard work on these papers and for beginning to illuminate the mysteries within them!