Following on from the excitement of the Dickens Exhibition, we’re now back to our everyday work of cataloguing, organising and assisting researchers in the reading room. But don’t assume that this is a boring part of the job: it’s in this way that many of our discoveries happen! How about this, for example, about the Red Dean?

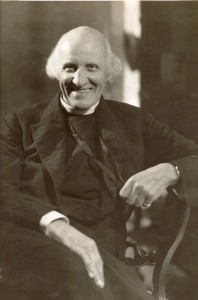

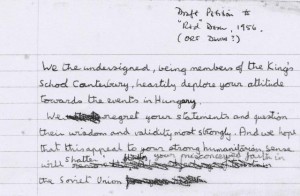

A few weeks ago, we were contacted by John Drew a former King’s School, Canterbury pupil. He asked about a petition in the archive, signed by boys at King’s School, which called for Hewlett Johnson, the Dean of Canterbury Cathedral, to condemn the Russian invasion of Hungary. Johnson had been – and remained – a stalwart supporter of Stalin’s regime throughout the twentieth century. Imagine our delight when John told us that he was the co-instigator of the petition, and the first signatory. He has very kindly given us permission to reproduce his recollection of the events.

In all the penny newspapers I was quite shocked to see

A long harangue against our Dean, professedly signed by me.

But I swear I didn’t sign it, this article obscene,

This vile and cheap attack upon Our President, the Dean.Are God and Russia then at strife and crypto-communists?

Surely in all this universe some compromise exists

Where God can keep his court amid cold, swirling, darkling mists

And leave a little outpost here where tolerance persists?He’s Our Dean, the Red Dean, and when the R.D. dies

I hope to see a thousand tears well from a thousand eyes

For one who held his principles through venom and the lies

Of the obscurantist leaders in the Councils of the Wise.– David Buchan, Grange House, 1956.

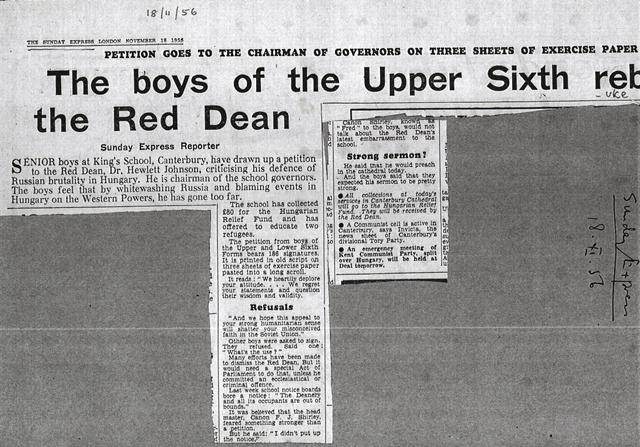

A recent biography of the Red Dean of Canterbury makes one of those slips of pen that bedevil all who write. It mentions that in November 1956 300 boys at the King’s School,Canterbury, signed a petition deploring the refusal of the Dean, Chairman of the School Governors, to condemn the Russian invasion ofHungary. Actually 186 boys signed. The slip is so minor it would not be noticed – except perhaps by someone who had tramped round the Cathedral Precincts to get the signatures.

There was a great deal of concern everywhere in Europe as the Russians sent their tanks into Hungary in the autumn of 1956 to depose the reform Communist leader, Imre Nagy, and so many Hungarians, having bravely fought to stop them, poured over the Austrian border. Oliver [Ford] “Orf” Davies, the well-known actor, drafted the text of a petition that was put together by several sixth-formers in Linacre House (neighbouring on the Deanery). I still have that draft, with amendments suggested (I believe) by the Headmaster, “Fred” Shirley, since (having rewritten it in clearer handwriting) it was I who, with Paul Niblock, had to collect the signatures and deliver it to the Dean.We got a good response to our petition until we reached the Grange, where we were rather nonplussed to run into quite a number of boys who refused to sign. Grange was something of a warren of dissidents (though the avant-garde composer Cornelius Cardew had left by then) and it was typical that when the History Master, Ralph Blumenau, wrote a somewhat impassioned editorial for the Cantuarian at the end of term beginning: Hungary bleeds… and dealing with the rape of Hungary, the Grange House Newsletter came back with a parody: Grange House bleeds… bewailing the theft of the house bath plugs.

Facetiousness aside, at the time of the petition David Buchan spoke for others in Grange (and perhaps elsewhere in the school) when he wrote the poem celebrating the dear old Dean and excoriating those who did him down. David was perhaps the one boy who could out-face Fred during daily Assembly in the Chapter House (Fred later spoke of the way that while all the other boys had their heads bowed in prayer or prep or a penny dreadful, David alone stared unflinchingly ahead). David saw better than I did that the petition was as much the outcome of a battle going on between Fred and the Dean as between the two sides in the Cold War.

I was naively unaware of Precincts politics and was actually nervous of missing Sunday Matins in the Cathedral, as Paul and I had to on account of delivering the petition to the Dean. The Dean was charming and, with his wife Nowell in attendance, sat us down to a salutary lesson in 20th century history, spiced with personal reminiscence. He did regret that the situation in Hungary had come to an armed intervention but he reminded us that, as we spoke, Britain and France were still acting in a 19th century imperialist style by attackingEgypt inSuez. The Dean left us with plenty to think about and ended by regretting, in a memorable metaphor, that an Iron Curtain had been erected between him and the boys at the King’s School.

I soon had more to be nervous about. My father was News Editor of Beaverbrook’s Sunday Express and, after I had told him that the boys were upset by the Dean’s refusal to condemn the Russian invasion of Hungary, he had sent a reporter down to the school on the Saturday to find out what was happening. An (accurate) report of the petition appeared in the paper the next day (November 18th) under the banner headline: BOYS OF THE UPPER SIXTH REBUKE THE RED DEAN.

I went out on a family exeat to Folkestone that day, blissfully unaware that reporters from every national newspaper except the Daily Worker were descending on the Precincts to follow up the story, eleven accounts appearing on the Monday (with a couple in local papers later in the week). I returned in the evening to hear that Fred wanted to see Paul and I. Fred appeared to be furious, though I now suspect (apart from snobbery about the gutter press) he was only rattled not to be in total control of a scenario that was (in fact) unfolding much as he would have wanted it to.

Paul and I returned from the dressing-down by Fred to face our tall, bespectacled and slightly gawky house-master at Linacre, Humphrey Osmond, and apologize to him for the disturbance to his day he had experienced. To our surprise, dry as he usually was, he said it had all been rather fun. Good old Humph, bless him.

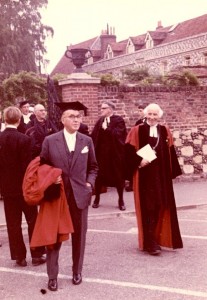

Fred got Miss Milward, his secretary and very much right-hand woman, to write a stinker to my father for dragging the name of the school through the press in a way likely to put off prospective parents from choosing the school. My father replied, repudiating the charge with his usual aplomb and good humour. His schooling had been in the world of newspapers and he could respect, without deference, both the Headmaster and the Dean. He recognized that King’s had been transformed under Fred – academically, aesthetically and athletically – and he also had a healthy regard for the Red Dean’s take on Christianity, often referring to his work in Manchester and his record of being one of the first to go and take a look at Red Russia and Red China. [I have a picture of him talking with the Dean on the Green Court the following summer].

Years later, after the fall of the Iron Curtain, I was appointed British Council lecturer in British Studies at ELTE, theUniversityofBudapest. Among other things, I organized a lecture series at the university whereby distinguished Hungarians who fledHungaryin 1956 and became British citizens, told their stories based on the theme of being Inside Two Cultures. By then, having visited Plot 301, the grave of Imre Nagy, I had a far greater appreciation of Hungarian history and understood that, while the 1956 refugees feared the return of a Rakosi-style Communist reign of terror, the Dean was haunted by the even more dreadful oppression of the Fascist thugs in 1944. Each day inBudapestI waited for my bus home across from the building where, in their District XIV HQ, the Arrow Cross mashed in the faces of those who had bravely hidden Jews. The events of 1944 and 1956 are as alive today inHungaryas are those of the 1848 uprisings R.W. “Duffy” Harris made central to his lectures to us on European history.

If you want to find out more about Hewlett Johnson, or any of our collections, have a look at our website. Please contact us with any enquiries which you may have.