When we last heard from William, he was in Paris, sampling the delights of the city and commenting on some of the most important episodes of the early nineteenth century. By the time he wrote to his father again, it was October, and he and his three friends had enjoyed ‘a most interesting journey’ through Switzerland. In spite of the excitement, William had been glad to receive a letter from his father, and ‘a double one from Thomas and my sister’. Detective work so far suggests that William’s sister, Margaret, was married to Thomas, both of whom are mentioned in every letter. William was relieved to be assured ‘of the welfare of my dear friends’, explaining:

“The farther we are removed from those who have a right to our affections, the more importance do we attach to every fresh arrival of intelligence from them.”

Of course, William’s journey was going to take him much further from his family than Switzerland.

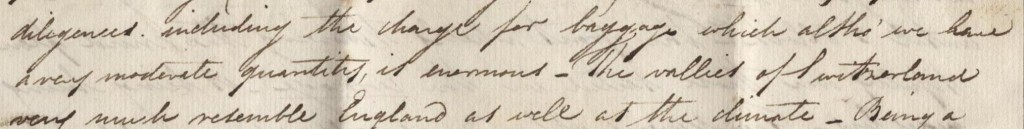

The landscape and the climate of the Switzerland, William explained, were largely the same as in England and ‘some of the cattle are as fine as our own’. After France, with its ‘endless straight roads’, the architectural eye found the ‘serpentine lines and hedges’ far more pleasing. William had little to say about Switzerland and his time spent in Geneva, only adding that there were delicious wild cranberries growing in the hedges on the road between Geneva and Sallanches. The journey from Geneva to the eventual arrival in Milan, however, offered plenty for William to write home about.

The landscape and the climate of the Switzerland, William explained, were largely the same as in England and ‘some of the cattle are as fine as our own’. After France, with its ‘endless straight roads’, the architectural eye found the ‘serpentine lines and hedges’ far more pleasing. William had little to say about Switzerland and his time spent in Geneva, only adding that there were delicious wild cranberries growing in the hedges on the road between Geneva and Sallanches. The journey from Geneva to the eventual arrival in Milan, however, offered plenty for William to write home about.

“As we approached Sallènche [Sallanches], the scenery gradually became mountainous and within half an hour of that place an object of the most sublime description burst on our more astonished senses – Mont Blanc! the highest mountain in Europe! Its summits clad with eternal snows, soaring far above the very clouds, illumined by the last golden rays of the setting sun. Imagination can hardly conceive anything to surpass it.”

Awed by the sight, William told his father:

In the contemplation of such a glorious scene as this, the mighty hand of an Omnipotent Creator is most evident to the most superficial and carries with it that feeling of dependence and submission to his will which it is impossible not to acknowledge.

This is not to say that William necessarily held views of religion which would seem antiquated and credulous to some today; long before the publication of The Origin of Species in 1859 there had been debate about the literal truth of the Bible and many discoveries which had led to new explorations of Christianity. Later on in this letter, William described the glacier of Bossons, which falls towards the ‘beautiful valley’ of Chamonix (‘Chamouny’ in William’s letters):

an enormous mass of frozen ice and snow descending from Mont Blanc into the verdant valley below. The novel effect it has to an eye unaccustomed to such sights is wonderful. The glaring purity of the ice, split into immense pyramids of very acute form, contrasted with a grove of dark mountain pine in the background while cultivation and verdure almost dispute its footing altogether appear more like enchantment than reality.

For all of his talk of enchantment and of an Omnipotent Creator, William then described the formation of the glacier like a nineteenth-century scientist:

“The glaciers are the remains of ancient avalanches, or masses of snow which roll down from the summits of the mountains when it has accumulated in heaps too large to remain there. This mostly happens in winter and spring and ‘tis said they fall with a noise loud as thunder. During the heats of summer they are constantly melting…. They have also a progressive or sliding motion into the valley imperceptible indeed, but it has been proved by experiment to be not less than 4 or 5 inches a day and this motion is the cause of the clefts and pyramids formed in the glacier….. Glaciers sometimes decrease in bulk and so seem to retreat in a very hot season as is the case with this of which I am now speaking and it has left a sad desolate site covered with large stones and pebbles without one single blade of grass to distract from the hideous picture. After a severe winter, acres of cultivation have been lost by their incontrolable [sic] advance.”

William’s romantic edge as a writer returns when he adds that:

‘The shadows on the pyramids or rather spires of ice produced by the melting snow are of the finest cerulean blue.’

I think that William’s commentary on the awe inspiring Mont Blanc landscape illustrates the psyche of the early nineteenth century gentleman: a Christian, a thinker and a scientist, all rolled into one.

Not everything about the mountain trek was picturesque, however; the lower hills were ‘partially concealed by the watery clouds sailing amongst them – the foreboders of the stormy day which followed’. Leaving Sallanches in the morning in ‘a strange 4 wheeled carriage for 3 persons called a ‘char-a-banc’ resembling the body of a garden chaise placed sideways’, William and his friends were annoyed to find that it rained ‘without interruption with great violence’ until 5 o’clock. The three in the carriage were spattered with mud and the fourth, riding a mule (they took it in turns), probably fared little better. There was little to be seen ‘through the pelting rain’ but what they could make out was ‘of a grand and wild character’. Never mind spending 3 hours crossing the channel; this stage of the journey sounds the most unnerving so far:

“Sometimes the road which was extremely rugged ran close to the edge of a steep precipice – in another part the rocks were several hundred feet above us. We saw several immense stones lying scattered about, hurled by the all prevailing hand of time from the cragged mountains. Several small torrents intercepted the route – full of pebbles as long as paving stones…”

‘So you can imagine’, he wrote drily, ‘we had a pretty rough jaunt of it.’

However, it sounds as if all four – William, Mr Brooks, Mr Angell and Mr Butts arrived safely at Chamonix, where they stayed (perhaps predictably) at the London Hotel, with views of Mont Blanc, the glacier of Bassons and the Mer de Glace from their windows. It’s starting to make me jealous of their holiday!

The four evidently made a trip to the ‘Jardin’ of Mont Blanc, part of the mountain walk which rises above the Mer de Glace, since William told his father that he was attempting to describe it in a letter to his sister. In his brief paragraph apparently responding to his father’s news in a previous letter, William makes an interesting reference to ‘Jane’, who he had sent his love to, along with his mother and sister, in all of his earlier letters.

“I am sorry to hear that Jane is no longer an inmate of your house but hope the change will be more agreeable to all parties.”

Who was Jane? It’s a mystery to me, at the moment, but I hope to do some more investigation and find out soon!

This letter also gives us the address of Mr Thomas Angell’s father, at 8 Church Row, Islington. William asked his father to write to Thomas’ father whenever William sent news, and that Thomas would ask his father to do the same. This small band of young architects were evidently becoming fast friends.

So having written from Milan, in an unusually clear letter (with only one layer of writing, though it’s all crammed in), William wished his father the best and signed off for a trip around Italy. More on that next time…

William’s fourth letter will be on display in the Templeman Library foyer for a limited period, along with some of the scientific and theological literature of his day.

PS. If you’re wondering about the horse, William was ‘very glad to hear [a] good account of poor Dick.’