Friday 7th October, 2022 marks 100 years since the death of Marie Lloyd, one of the most famous and popular music hall stars of the late 19th and early 20th century and “Queen of Comediennes”.

Max Tyler Music Hall collection, University of Kent

Early years

Born Matilda Alice Victoria Wood on the 12th February 1870, Marie was the eldest of nine children. All of the Wood children would take their turn on the stage, performing together as early as 1879 as a minstrel act called the ‘Fairy Bell troupe’, with a number of her siblings going on to have successful careers in their own right.

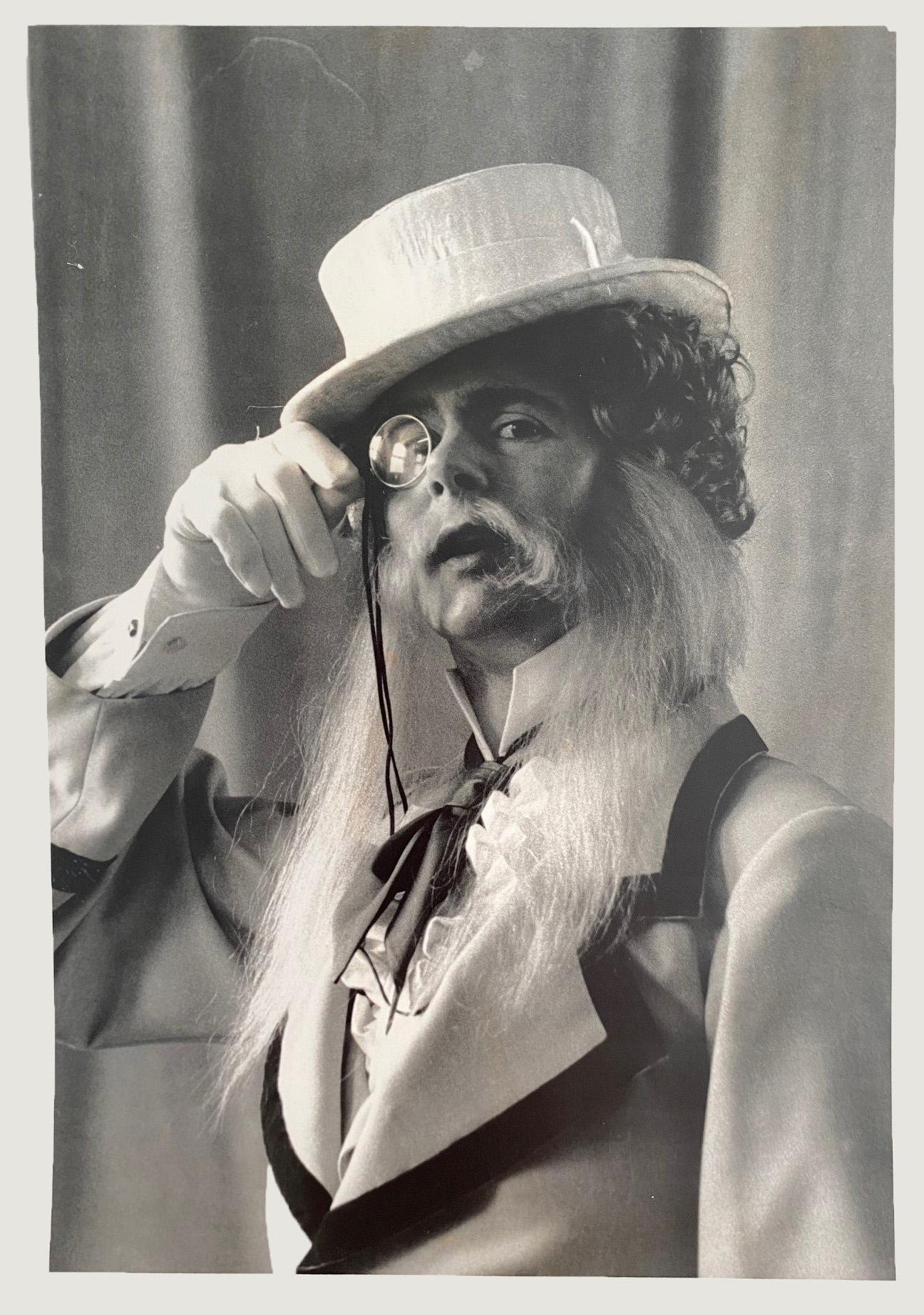

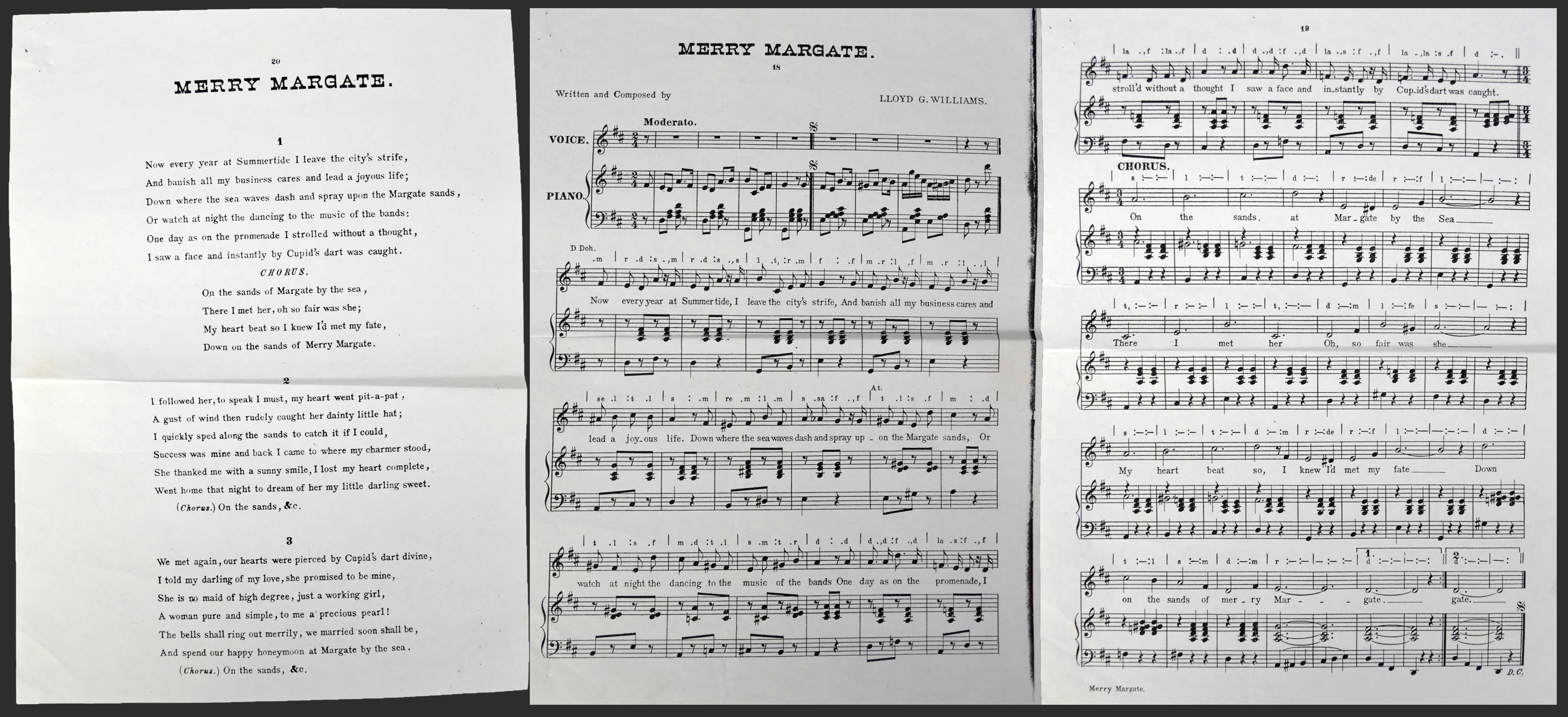

In 1885 Lloyd made her first professional solo performance, performing as ‘Bella Delmere’ at the Royal Eagle Music Hall on 9th May, aged just 15. However, this name was quickly changed and by June of that year she was performing as ‘Marie Lloyd’. Despite not having the best of singing voices, Marie oozed charm and was a natural comedian, making her an instant hit. Her popularity continued to grow, and she continued to get bookings at halls across London, performing songs such as “The Boy I Love Is Up in the Gallery”, “She Has a Sailor for a Lover” and “Wink the Other Eye”. By 1891 Lloyd was a household name, pulling in large crowds at halls across Britain, and starring in the Theatre Royal at Drury Lane’s Christmas pantomimes alongisde stars such as Dan Leno. As her star continued to rise, her agent reported that Lloyd was fully booked up for years at the best houses across the UK, and that her salary ran from £250-£300 a week, sometimes as much as £700 a week at the height of her career.

Reputation, charity, and controversy

Part of Lloyd’s appeal was that she did not appear on stage to be bound by the moral constraints of the time – her songs were cheeky and risqué, and she would play with the audience. However, this cheekiness did give her somewhat of a reputation. In 1895, Lloyd added the song ‘What’s that for, eh?’ to her act. The song tells the tale of a schoolchild who, when she asks her parents awkward questions, gets unsatisfactory answers. So she goes to her friend ‘Johnny Jones’ for help, and he teaches her the facts of life. And while the lyrics were not indecent, when Marie performed the song she was suggestive, winking to the audience and gesturing.

“What’s that for, eh? Tell me Ma

If you don’t tell me I’ll ask Pa”

But Ma said, “Oh its no thing shut your row”

Well, I’ve asked Johnny Jones, see

So I know now.”

The song and it’s performance was so controversial that it was cited as evidence in a hearing of 1896, when the Oxford Music Hall was threatened with having its licence withheld.

In October 1906 Lloyd was elected the first president of the Music Hall Ladies Guild. The organisation helped the wives of artists who were unable to perform and make money, providing food and resources to them and their families. They also supported young people, helping boys find work as messengers or call-boys. Some members of the Guild would use it as an opportunity to network and improve their social standing, however Lloyd did not have time for this pretentious self-promotion. She was well-known for her incredibly generosity and charitable giving, and preferred to have fun and entertain at Guild events.

Lloyd also petitioned for Music Hall artistes to have more rights and fair contracts. She used her clout as a well-known and celebrated artist to stand up for the community, and in 1899 she took a manager to court over a dispute with her contract, and won. This accomplishment was recognised by her peers, who presented her with gifts to mark her generosity in defending artist’s rights. She wrote in The Era “I am, and always have been ready and willing to help my brother and sister artists by every means in my power in anything that is for their good”. She was integral in developing the National Alliance, a group that wrote a charter that was sent out to theatre managers outlining the terms by which performers wished to work. The refusal by some to sign this charter led to a number of theatres being “blacklisted” by artists, and over two thousand performers taking to the streets to protest contract conditions.

1912 saw the first ever Royal Command Performance (later known as the Royal Variety Show) at the Palace Theatre, Shaftesbury Avenue, London, with acts performing on stage in the presence of King George V and Queen Mary. To some amazement, Marie Lloyd was left off of the bill. According to Graeme Cruickshank in the Spring 2012 volume of The Call Boy, this was possibly at the direction of Alfred Butt, Oswald Stoll and George Ashton (producers of the show) in their attempt to make the show “family friendly”. Some thought it may also have been due to her association with the music hall strike, or that it was simply a case of balancing the bill and not oversaturating it with female comedic performers. In public, Lloyd took the slight professionally and with dignity, but there is evidence that she was furious – Alfred Butt even wrote to the palace warning that Marie Lloyd was to write to the King regarding her omission (although there is no evidence of her ever doing this). Possibly telling of her feelings on the matter, on the night of the performance Lloyd put on her own show at the London Pavilion in Piccadilly, and left for Paris immediately after that performance. Albert Chevalier (who was also left off of the billing) said of it “The whole arrangement as it stands is really extraordinary. Who is there more representative of the variety profession? Miss Lloyd is a great genius, she is an artist from the crown of her head to the sole of her foot…”.

Marie continued to perform throughout World War I, performing new songs, including some with a military theme. She also frequently visited hospitals to visit wounded servicemen, and toured munition factories to boost morale.

“Now, I do feel so proud of you, I do honour bright

I’m going to give you an extra cuddle tonight

I didn’t like yer much before yer join’d the army, John

But I do like yer, cocky, now you’ve got yer Khaki on.”

Despite all her charitable efforts throughout her career and during the war, Marie was never officially recognised in the way her colleagues, such as George Robey CBE, were. This had an impact on her bitterness in later life, which was only exacerbated when she was overlooked again for the 1919 Command Performance.

Off stage life

Despite her successes, Lloyd had a troubled personal life. She was married three times, and experienced domestic abuse during two of them. She married Percy Charles Courtenay in 1887, but the marriage was unhappy, and filled with violence, drunkeness and jealousy. The couple divorced in 1894, after Courtenay discovered that Lloyd had started an affair with fellow performer Alec Hurley. Hurley and Lloyd married in 1906, however the pair were effectively seperated by 1910 after they had consistent marital probems. Lloyd began an open and passionate affair with Bernard Dillon, a jockey. Hurley initiated divorce proceedings in 1911. Sadly the relationship between Lloyd and Dillon was not a happy one, marred by Dillon’s jealousy, drunkeness, and gambling addiction. Despite this they married in 1914. He was violent and abusive throught the rest of Lloyd’s life.

Sadly, Lloyd was also a heavy drinker, particularly in later life, perhaps a consequence of her troubled personal life. She would often have violent fights with Dillon, with Lloyd sometimes needing to apply make up to cover the bruises. As she moved in to her 50s she fell in to a depression, and would no longer hide her feelings of bitterness and anger. In July of 1920 she took Dillon to court over his violence, making their private life very much a topic of public record. This resulted in him being ordered by the court to “keep the peace” for the next twelve months, a sentence that was apparently requested by Lloyd.

In the later years of her life, Lloyd was in financial trouble (in part due to Dillon’s gambling debts) and needed to work in order to get by. Her drinking and ill health made her less and less reliable, sometimes only performing for a fraction of the time that she was scheduled. She began to forget her lines and would sometimes stumble on the stage, so much so that stagehands would be asked to be on call to help her if she became unsteady. In order to save money, in early 1922 she moved in with her sister Daisy, and by the time of her death Lloyd was virtually penniless.

Death

Lloyd worked right up until days before her death, having been on tour for much of 1922 despite being unwell. Her last performance at the Edmonton Empire was the Tuesday before her death. Prior to the performance, she complained to Sidney Bernstein (the owner of the theatre) of a stomach ache and was shivering. Bernstein tried to persuade her to go home, but to no avail. Her doctor was called and he gave her some medication, before staying to watch her performance from the side of the stage. During the performance Lloyd staggered and fell, making the audience laugh thinking it was part of her act. After the show Lloyd collapsed and was taken home in a taxi, unconscious. She did not regain consciousness and died at her residence in Golder’s Green, 7th October 1922 at the age of 52.

Funeral and legacy

Lloyd’s funeral was held at Hampstead Cemetery on 12 October, 1922. More than 50,000 people turned out on the streets of Hampstead to watch her funeral cortege. It was estimated that 120,000 people visited her grave in the following weeks, with queues stretching out from the gates of Hampstead Cemetary. Many newspapers and fellow performers paid tribute to Lloyd in the days after her death. T.S. Eliot wrote a moving tribute to her in The Criterion of January 1923. He said of Lloyd…

“Marie Lloyd was the greatest music hall artist in England: she was also the most popular… It is evidence of the extent to which she represented and expressed that part of the english nation which has perhaps the greatest vitality and interest… Whereas other comedians amuse their audiences as much and sometimes more than Marie Lloyd, no other comedian succeded so well in giving expression to the life of that audience, in raising it to kind of art.”

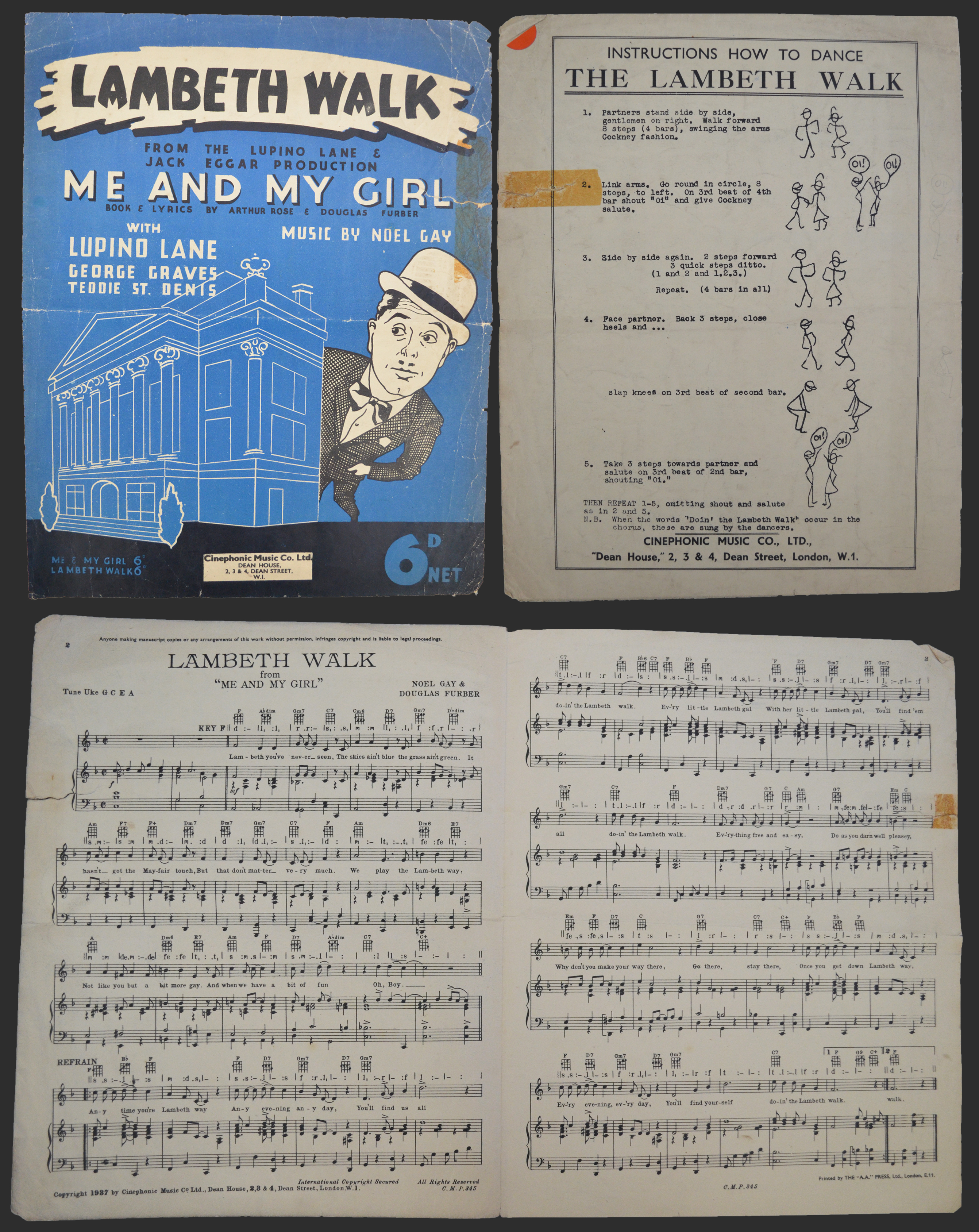

Many of the songs sung by Lloyd are still known today, including “My Old Man Said Follow the Van”, “A Little of What You Fancy Does You Good”, and “Don’t Dilly Dally On The Way”. A memorial tablet to Lloyd was installed in the vestibule at Tivoli cinema (what was the Tivoli Theatre) in the Strand in 1944, on the 21st anniversary of her death. Lloyd was also commemorated in 1977 with a blue plaque at her previous residence, 55 Graham Road in Dalston. In media, a stage show and BBC drama have been created depicting the life of Marie Lloyd.

Sources

- Midge Gillies, Marie Lloyd: the one and only (Gollancz, 2001). Max Tyler Music Hall Collection (ML 420.L56 GIL)

- From the archive: The death of Marie Lloyd (Guardian, Oct 9th, 2009) https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2009/oct/09/death-of-marie-lloyd.

- T.S. Eliot, In Memoriam: Marie Lloyd (January, 1923). Main Collection (PER AP 4.C8 VOL 16)

- Graeme Cruickshank, Marie Lloyd and the 1912 Command Performance – the truth? (The Call Boy, Spring 2012). Max Tyler Music Hall Collection (no reference)

- Marie Lloyd Dead (Aberdeen journal, Oct 9th, 1922). Max Tyler Music Hall Collection (MWT/RES/109)

- Marie Lloyd (Wikipedia, no date). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marie_Lloyd

- Marie Lloyd (1870-1922) (Stage Beauty, no date). http://www.stagebeauty.net/th-frames.html?http&&&www.stagebeauty.net/lloyd/lloyd-m2.html

- LLOYD, MARIE (1870-1922), (English Heritage, no date). https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/blue-plaques/marie-lloyd/

Note

As with many acts at the time, Lloyd performed some songs that contained offensive and racist terminology, and we can not with good conscience speak of her success and popularity without mention of this. Music Hall song and performance was in many ways a reflection of social attitudes at the time, and this does not exclude those parts of white, British history that are offensive and repellent. We can see this in our collection of music hall songsheets, with some containing racist slurs and offensive depictions, imperialistic attitude, and that make light of marital violence, misogyny, and the class divide. Music Hall rose in a time of expansion of the British Empire and popular imperialism. Songs performed by both male and female artists played with notions of power, or leaned on stereotypes to connect with the audience.