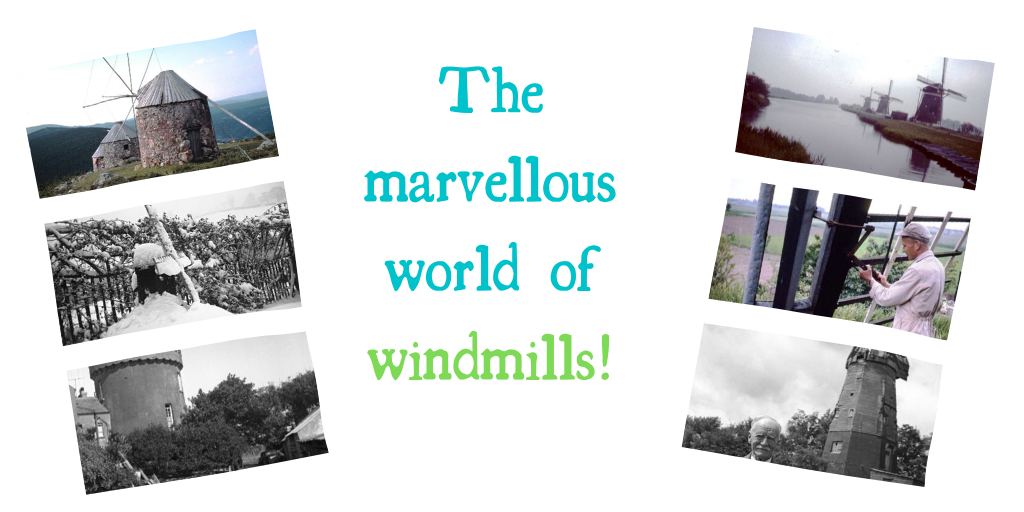

Did you know that Special Collections & Archives hold not one, not two, but four collections relating to windmills and their history? To celebrate National Mills weekend (being held virtually over the bank holiday, 9 – 10 May 2020) we thought we’d put together some interesting facts based on our marvellous mill material! (Alliteration encouraged but not necessary.)

We challenge you not to find windmills awesome after this post

1. Windmills are important sources of local history

We’re so used to living in an age with electrical everything, but before the industrial revolution happened mills were vital sources of power across the UK and Europe. They didn’t need to be near water sources to generate energy and were used for all kinds of work, especially grinding wheat to make flour – vital in a world before mass imported food.

Because mills could be found almost everywhere until the 19th century, they’re a unique source for exploring local history and a great starting point for archive research: who owned the mill? What was it used for? Where was it in the community and how long did it operate for? If it’s no longer around, what’s replaced it on the site? Who worked in mills and how much did they earn? Mills are a great resource for economic, local and art historians alike.

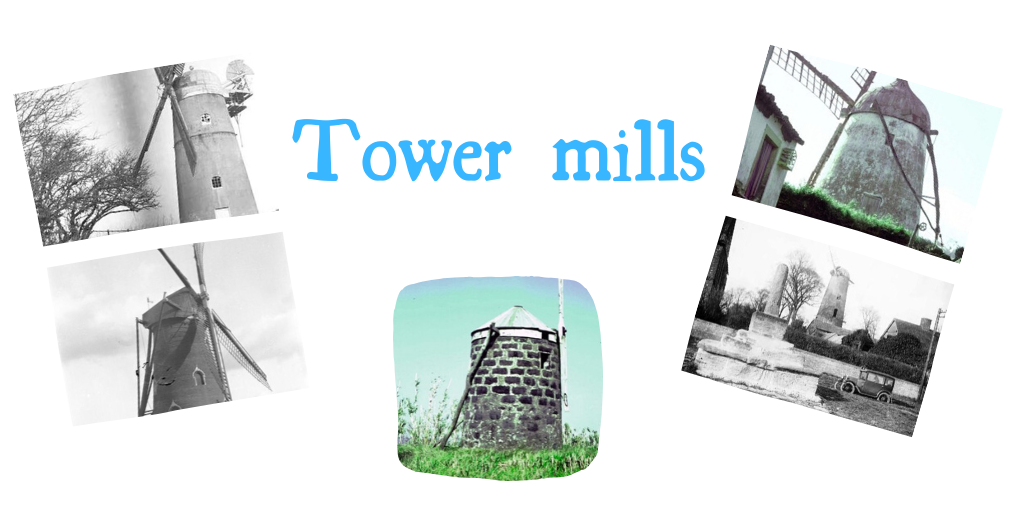

2. Know your mill types: tower mill

Lots of tower mills: note the brick and cylindrical body

If you’ve been following our #WindmillWednesday hashtag on Twitter, you’ll notice that there isn’t just one type of windmill to explore. We traditionally associate windmills with tower mills – they’re fairly cone-like in shape, often brick-based and the sails are attached to a wooden roof that can rotate in the direction of the wind. Tower mills have existed since the 13th century but they became popular from the 16th century onwards; however they’ve always been more expensive to build than other types of mill. In the UK, the tallest existing tower mill can be found at Moulton in Lancashire.

Moulton windmill’s workers must have been extremely fit to get all the way to the top (image taken in 1938)

3. Kent has so many windmills there’s an entire book about them

At one point, Kent had over 400 windmills – with Deal and Sandwich hosting 6 each! Today 12 still exist; Kent County Council look after 6 of them. The definitive work about Kent’s windmills was written by historian William Coles-Finch (1864 – 1944) in 1933. Windmills and Watermills was republished in 1976; we have several copies of each edition. We often get asked “why do you have things relating to windmills anyway?!”; our answer – alongside the local history and generally awesome elements – relates to the creators of the three main mill collections we hold. Keep reading for more information…

4. Know your mill types: post mill

Post mills, not to be confused with post boxes

Post mills are the earliest known type of European windmill and generally the most affordable to build. They can be recognised easily – they have a blocky, boxy structure that sits on top of one post, often hidden by a cylindrical base. Architecture aside, the main difference between tower mills and post mills is that in post mills the mechanisms are enclosed within the box of the mill (around a single post, hence the name) and it’s this part that turns. In comparison to a tower mill, this is a huge difference – in tower mills it’s only the top of the mill that rotates. Sometimes you’ll see post mills without the cylindrical base, but as it’s pretty useful for storage many are built with this area included as part of the design. In the UK, the longest working post mill can be found in Outwood, Surrey; the oldest non-working mill is in Great Gransden, Cambridgeshire.

Great Gransden windmill shows off its best side (1979)

Miller Stanley Jupp looks mighty proud of his Outwood windmill, as he should (1961)

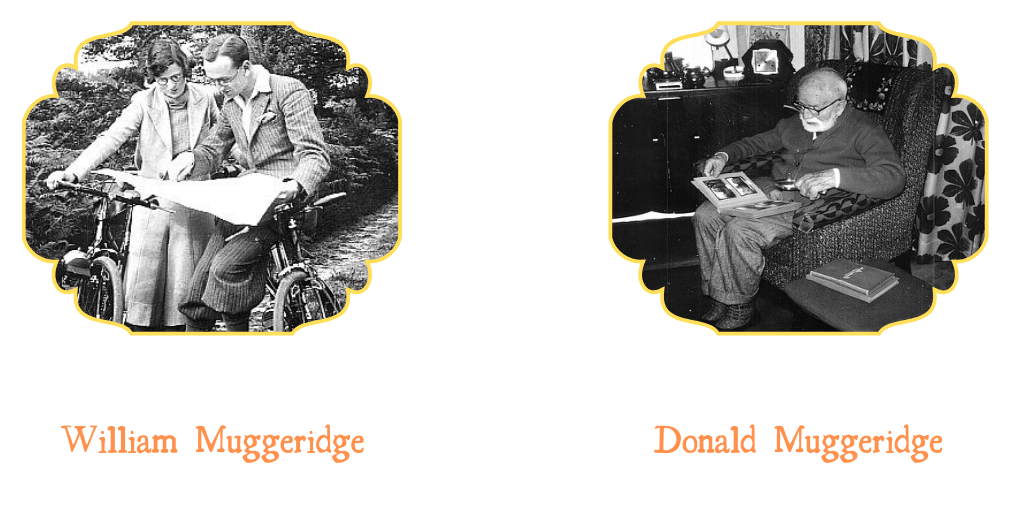

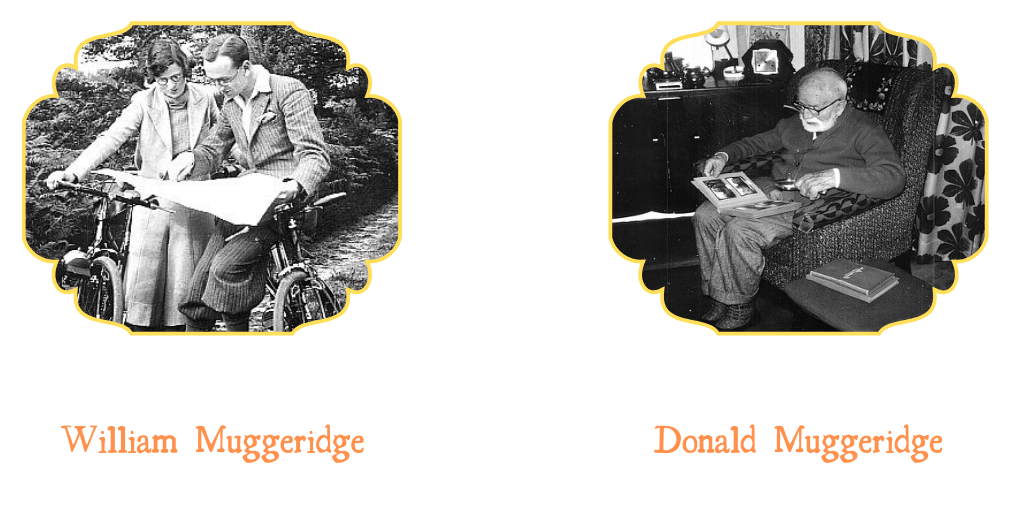

5. The Muggeridge family really liked windmills

The Muggeridge family – father and son

The largest collection of mill material we look after belongs to the Muggeridges. William Burrell Muggeridge (1884 – 1978) started taking images of mills in 1904 and continued for most of his life; we hold his glass plate photos. William passed his love of all things windmill onto his son, Donald (1918 – 2015) who spent much of his spare time cycling around the UK with his wife Vera. Vera and Donald were interested in all things heritage-related and windmills formed a large part of that interest. Donald’s photographs also reside with us. You can read more about the Muggeridges here.

6. Know your mill types: smock mill

Smock mills in all their finery

Like tower mills, smock mills only rotate through the top of the building where the sails are attached. The main difference between smock mills and tower mills is that smock mills are generally constructed of wood and have 6 or 8 sides, whereas tower mills are made of brick and generally cylindrical in shape. Because of their multiple sides smock mills resemble smocks traditionally worn by farmers. In the UK you can find the oldest existing smock mill in Lacey Green, Buckinghamshire.

Lacey Green smock mill looking mighty atmospheric (1934)

7. Not just the UK: windmills across the world

The majority of our mill collections focus on UK windmills, but they’re well documented across Europe and beyond. The Netherlands is particularly famous for milling – in 1850 they had 10,000 windmills in operation out of Europe’s 200,000 total! After the Second World War Donald Muggeridge moved to North America (Canada then California), so his collection contains many photos of American mills and others across the globe from his travels. You can explore the listing of Donald’s adventures here.

8. C.P. Davies was also a big mill fan

Our other significant mill collection belonged to C.P. Davies, a Kent based librarian in the 20th century. The Davies collection differs from the Muggeridges’ in that it is much more text and ephemera based – you can find newspaper cuttings, articles, pictures and handwritten notes amongst its c.100 boxes. Davies was primarily focused on mills along the south coast (Kent and Sussex), but there’s information about a wide variety of mills across the UK and Europe. You can browse the listing of the collection here.

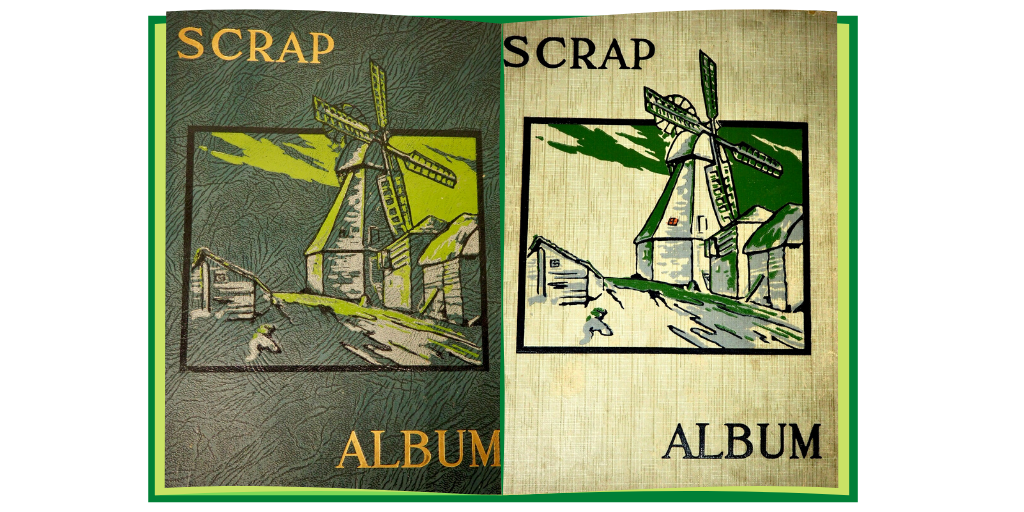

9. One final Kent name to remember: the Holman family

Two of the scrapbooks from the Holman family. There’s at least one cute sheep photo within.

If you’ve visited Special Collections & Archives on an open day in the past few years, you may well have seen one of our gorgeous windmill scrapbooks. These scrapbooks were made by John Holman; his collection also includes engineering notebooks and many other memorabilia relating to mills. The Holmans were a famous milling family in Kent; they built twelve wooden smock mills across the county between 1793 and 1928, of which six still stand. The Holman milling business (which included engineering and designing mill parts too) ran for 150 years. If you’re interested in finding out more about them, The Mills Archive have a wonderful biography of the Holmans online.

10. Mills have switched from practical structures to heritage buildings

Nowadays most mills aren’t in use for power generation as there are far more efficient methods, and the number of buildings that still exist are far fewer. As you might expect given their structure and components, windmills are at risk from bad weather, neglect and occasionally fires – there are a lot of photos across all our mill collections that record the damage time does to these marvellous machines. However many mills now are managed either through county councils (Kent County Council looks after eight of twelve remaining) or via volunteer charities. They often open for visitors in the summer months, and initiatives like the National Mills weekend help to raise support and awareness.

If you’ve read this far…congratulations! You may now call yourself a molinologist, aka someone who studies mills! Maybe one day you will find yourself seeking out windmills far and wide, like the author of this blog:

Windmills: guaranteed to make you happy!

Resources and references:

Kent County Council have a fantastic resource pack to teach children (and adults) about windmills: https://shareweb.kent.gov.uk/Documents/Leisure-and-culture/heritage/heritage-education-packs/windmills-education-pack.pdf

The Mills Archive is a fantastic site for molinologists of all ages but we particularly like their biography of the Holman family: https://millsarchive.org/explore/features-and-articles/entry/158534/holman-bros.-millwrights-of-canterbury-a-history/6817

For much-needed reading, the Wikipedia pages on windmills are a great place to start (and very thorough): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Windmill

The majority of our windmill collections are catalogued; you can view details of their contents here: https://archive.kent.ac.uk/TreeBrowse.aspx?src=CalmView.Catalog&field=RefNo&key=MILL

We are continuously cataloguing our library of mill-related books, and you can view up to date listings on LibrarySearch: https://librarysearch.kent.ac.uk/client/en_GB/kent/search/results?qu=windmill&qf=LOCATION%09Location%091%3ASCA%09Special+Collections+and+Archives&if=el%09edsSelectFacet%09FT1&ir=Library&isd=true

All photographs used in the hybrid images in this post are from our Muggeridge collection: https://archive.kent.ac.uk/Record.aspx?src=CalmView.Catalog&id=MILL%2fMUG