Following on from the Weatherill post (which I have to say I had a lot of fun researching and writing), I am continuing my crusade to bring lesser-used collections out into the light of day. This time, it’s the turn of the Maddison Collection, which the Templeman has housed for some decades. I’ve got a soft spot for this collection, even though it’s about the history of science; I think this area is one of the most interesting parts of our early-modern past. After all, science or natural theology has only recently become a discipline in its own right. For many centuries, it was closely tied with sometimes drastic changes in society and religion and even in the way people viewed themselves and their cultures.

Engraving of Joseph Priestley

The Maddison Collection contains many books about influential scientists and natural theologians from the 17th to the 19th centuries. One interesting individual, many of whose works are included in this collection, is Joseph Priestley, 1733-1804. Priestley is a difficult man to pigeonhole: historians have long debated how his differing values and views contributed to his scientific, theological and reforming works. Priestley carried out experiments with air and electricity, was one of the first people to discover the existence of oxygen and also discovered that elements other than metal and water could conduct electricity. An effusive biographer described Priestley as a man ‘whose discoveries diffuse brilliancy over his age and nation’ (p. 53, Life of Joseph Preistley, 1804). However, it was not so much his scientific discoveries as his religious and political views which led to Priestley fleeing Britain in 1794 for refuge in America.

Priestley was a Dissenter; he was raised as a Calvinist but became one of the founding members of the Unitarian Church. As one of a large group of individuals whose religious beliefs fell outside the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion which contained the orthodoxy of the Church of England, Priestley was unable to attend university, vote or take part in other areas of public life. His personal beliefs were extreme even for the dissenting Christians; he believed that Christianity should be stripped back to its ‘primitive’ faith: the religion which sprang up amongst the early Church. Speaking after a mob had pulled down his house in Birmingham, Priestley told an assembly of dissenters that one of the virtues of early Christianity was as ‘a sect everywhere spoken against’, just as his own denomination was at that time (p.7, The Use of Christianity, 1794). Priestley was also a Millenarian, believing in the imminent second coming of Christ and the end of the world.

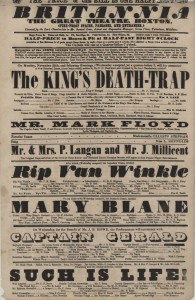

Title page from 'The Use of Christianity...'

Although he became a dissenting minister in 1755, his radical views were perceived by some of his first congregation in Needham to be too extreme. Perhaps he would have lived a quiet life if his religious views had not underpinned his scientific work, which he believed would show the true order of the world ordained by God and expose the injustices in society. Ironically, his belief in the divinely ordained nature of the world limited his scientific work, especially on the components of air, which Antoine Lavoisier pioneered by attacking phlogiston theory. In some ways Priestley was a true child of the Enlightenment, believing that progress could be achieved through scientific discovery, religious debate and increased freedom.

This was the spirit which initially welcomed the French Revolution, seeing the people of France rising up against their tyrannical monarchs to create a newly egalitarian society. Priestley remained a firm supporter of the French Revolution throughout his life, quoting Edmund Burke in calling it ‘the most astonishing [event] hitherto…in the world’ (p. 1, Letters to the Right honourable Edmund Burke, 1791). However, others who had initially supported the Revolution, including Burke, grew wary of the increasing radicalism which began to feel too close to Britain’s shores for comfort. Priestley was exasperated by Burke’s change of heart, claiming it was strange ‘that an avowed friend of the American revolution should be an enemy of that in France, which arose from the same general principles’ (p. iv, Letters to the Right honourable Edmund Burke). There were still a core group of dissenters who saw the French Revolution as an embodiment of the fair society which Priestley expected divine providence to lead England towards. It was the meeting of a small group of these dissenters in Birmingham on 14th July 1791, to celebrate the anniversary of the storming of the Bastille in France, which set of a series of events which drove Priestley from the country.

In John Corry’s biography of Priestley, he described the events of that evening:

While the friends of rational freedom were…celebrating one of the most important events recorded in the history of man; the mob increased in numbers and insolence. (p.26, The Life of Joseph Priestley)

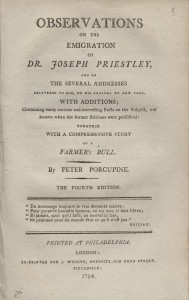

Title page from 'Observations on the Emigration of Dr. Joseph Priestley'

A pamphlet produced by an American writer, William Cobbett, and reprinted in London described the events rather differently; Priestley had organised a ‘feast’ to commemorate the French Revolution in Birmingham which caused ‘convulsions’ amongst the ‘scandalised’ people of the town for celebrating ‘events which were in reality a subject of the deepest horror’ (p. 4-5, Observations on the Emigration of Dr. Joseph Priestley, 1798) . The fear of revolution spreading and chaos, perhaps even another regicide, sweeping across a country which had suffered its own Civil War a few generations earlier, was a catalyst for a mob to descend on the celebration. The Report on the Trial of the Rioters reported around 300 people ‘crying church and King in a riotous manner’ descending upon several houses of known dissenters, including Priestley’s, and a meeting house, destroying the furniture and the buildings (p.92, Report on the Trial of the Rioters, 1791). There were suspicions at the time that there had been some complicity on the part of the authorities in organising the attacks, and Priestley, in several angry publications on the events, stated ‘the bigotry of the High Church Party [was] the cause of the riots’ (p.59, An Appeal to the Public, 1792).

At any rate, Priestley complained that both his scientific equipment and his library had been destroyed, and that ‘some of you intended me some personal injury’ (p.42, A Letter to the Reverend Joseph Priestley, 1791). Cobbett suggested that although ‘no personal violence’ was offered by the mob, some kind of pond-ducking of the offending individuals might have caused less destruction than their leaving their homes to be ransacked (p.5, Observations on the Emigration of Dr. Joseph Priestley). Priestley fled to London initially, but after three years there was still public anger at Priestley, in particular for his dissenting and radical views. During this time, Priestley wrote to the people of Birmingham, accusing them ‘of the greatest injustice and cruelty’ (p. xi, An Appeal to the Public). The English, he said, boasted of the rule of law in their country, yet Priestley himself had been punished outside the law, without trial.

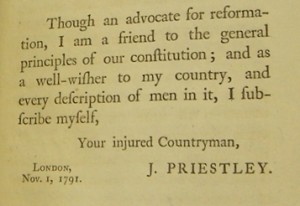

Preface to 'An Appeal to the Public'

He added ‘my coming to Birmingham was by no means the cause [of the riots] as is now asserted’; ‘the French Revolution was not the true cause of the riots’ because if the motives had been purely political, the mob would not have burnt down the meeting house, thus singling out the Dissenting congregation(p. 50-52, An Appeal to the Public).Thomas Belsham, in an address delivered in Hackney on the occasion of Priestley’s death added, ‘he seldom meddled in politics’, echoing Priestley’s own wounded defence in his Appeal to the Public…, in which he signed himself ‘your injured Countryman’ (p. 46, Zeal and fortitude in the Christian ministry illustrated and exemplified…, 1804; p. xv, An Appeal to the Public).

Priestley’s wounded entreaties to the people of Birmingham did not go undefended: one Birmingham resident published a pamphlet soon after Priestley’s letter in which he claimed Priestley’s accusations ‘call loudly for refutation’ (p.5, A Letter to the Reverend Joseph Priestley). While the ananymous writer agreed that ‘the injuries which you [Priestley] have sustained…are…a subject of deep and sincere regret’, Priestley ought to use ‘more discriminate terms’ in his address than simply the inhabitants of Birmingham (p. 3-6, A Letter to the Reverend Joseph Priestley) . Indeed, the author went on, if the mob’s attack was deliberate, it should be taken as ‘strong proof that your character and conduct among them had been eminently obnoxious’ (p.7, A Letter to the Reverend Joseph Priestley). With slightly more humour, the American pamphleteer claimed that Priestley preached Deism amongst the people of Birmingham, ‘which no-one understood’. Furthermore, ‘those who know anything of the English dissenters know that they always introduce their political claims and projects under the mask of religion’ (p.3, Observations on the Emigration of Dr. Joseph Priestley). The Birmingham author also suspected Priestley of supporting a revolution in England in the same way as the French had carried out their own.

Title page from 'Very familiar letters...'

The more comical, but equally anti-Priestley Very Familiar Letters, addressed to Doctor Priestley was supposedly penned by a townsman of Birmingham, John Nott, who maintained that he was ‘a little before-hand’ and ‘getting up in the world’ (p.2-3, Very Familiar Letters…, 1790). As a literate but working man, Nott represented the people whom Priestley considered as powerless as himself in the government of England. Nott’s ability to read meant that he could study Priestley’s books, and described the author as growing ‘witty in your old age’ (p.3, Very Familiar Letters…). However, the format of the pamphlet as spoof letters allowed the author to complain ‘I don’t take it mighty civil of you not answering my last two letters’ (p. 8, Very Familiar Letters…). While the general tone of this pamphlet is comical, poking fun at the comman man’s perspective, there is a serious note to its ending. Narrating how Priestley has supposedly changed the name of his home from ‘Foul-lake’ to ‘Fair-hill’, Nott comments:

“I’m afeard, as we have catch’d you at putting fair for foul…of putting darkness for light, and bitter for sweet, and evil for good.” (p. 12, Very Familiar Letters…)

The fate of the convicted rioters

These replies to Priestley’s angry addresses demonstrate that while not everyone wanted to see Priestley’s house torn down, there were real fears that the chaos and violence of the French Revolution was being invited into England by dangerous radicals.The sentence on the two men convicted of attacking Priestley’s property was severe: John Green and Bartholomew Fisher were found guilty and sentenced to death. Fisher was later pardoned, but Green was executed (p.98, Report on the Trial of the Rioters).

In 1794, Priestley addressed his congregation in Hackney in a farewell sermon, entitled ‘The Use of Christianity, especially in difficult times’. He was leaving for America, somewhat against his hopes, as he explained ‘unforeseen circumstances occur, and all our plans are deranged’ (p 4-5, The Use of Christianity, especially in difficult times). In spite of this, he urged the Dissenters to continue in their beliefs, explaining that:

The feelings of those who are merely exposed to the malignity of others, without feeling any thing of the kind themselves are serene…attended with a consciousness of superiority of character and of greater advances in intellectual improvement. (p.9, The Use of Christianity, especially in difficult times)

Although he made little reference here to the anger he expressed in 1791, it is clear that Priestley felt himself to have been targeted by the malicious bigotry of others.

'The Life of Joseph Priestley'

In America, Priestley’s attempts to stay out of politics and concentrate on his scientific and theological research were short lived. It was William Cobett’s pamphlet which accused Priestley of treason, claiming that when a man made attempts to convert individuals to his beliefs, his life, both public and private, became a fair topic for open discussion. ‘When the arrival of Dr. Priestley in the United States was first announced,’ Cobett wrote, ‘I looked upon his emigration as no more than the effect of weakness.’ (p. 1, Observations on the Emigration of Dr. Joseph Priestley) After some time, however, it became clear to the author that Priestley wanted to foment further revolution in America, where the civil wars were an even closer memory than they had been in England.

Although family tragedy struck the Priestleys in America, with Priestley’s wife and son dying within two years of their arrival, Priestley gained some success and a degree of peace in his exile. Of course, the revolution in Britain did not happen, although civil violence in France dragged on for another hundred years. Today, Priestley is remembered for his scientific discoveries while both the religion which fuelled his research and the politics which he believed to be the immediate result of his beliefs and his discoveries are largely overlooked. It probably says something about the way we view the world now that we find it difficult to understand how Priestley saw the world through the triple lens of his radical beliefs, of which his science appears to have been the most conservative. Despite this, it’s Cobett’s pamphlet which seems to hold the most resonance for me, when he says of Priestley, which might be said for many of us:

An Utopia never existed anywhere but in a delirious brain (p. 67, ‘Observations on the Emigration of Dr. Joseph Priestley)

Priestley may never have found his utopia, but perhaps it’s trying to understand and debate people’s varying beliefs in science, politics and religion which get us closest to Priestley’s ideal of utopian society.