To celebrate the inaugural #musichallvarietyday on Saturday 16th May, 2020, we thought we’d tell you a bit about one of our magnificent theatre collections, the Max Tyler Music Hall Collection!

In June 2018 Special Collections & Archives were lucky enough to receive the personal music hall memorabilia collection of Max Tyler.

Who was Max Tyler?

Max was the historian and archivist of the British Music Hall Society. A retired bank manager, Max looked after the society’s theatrical memorabilia and was an expert in the field, particularly in the subject of seaside entertainment and obscure music hall tunes!

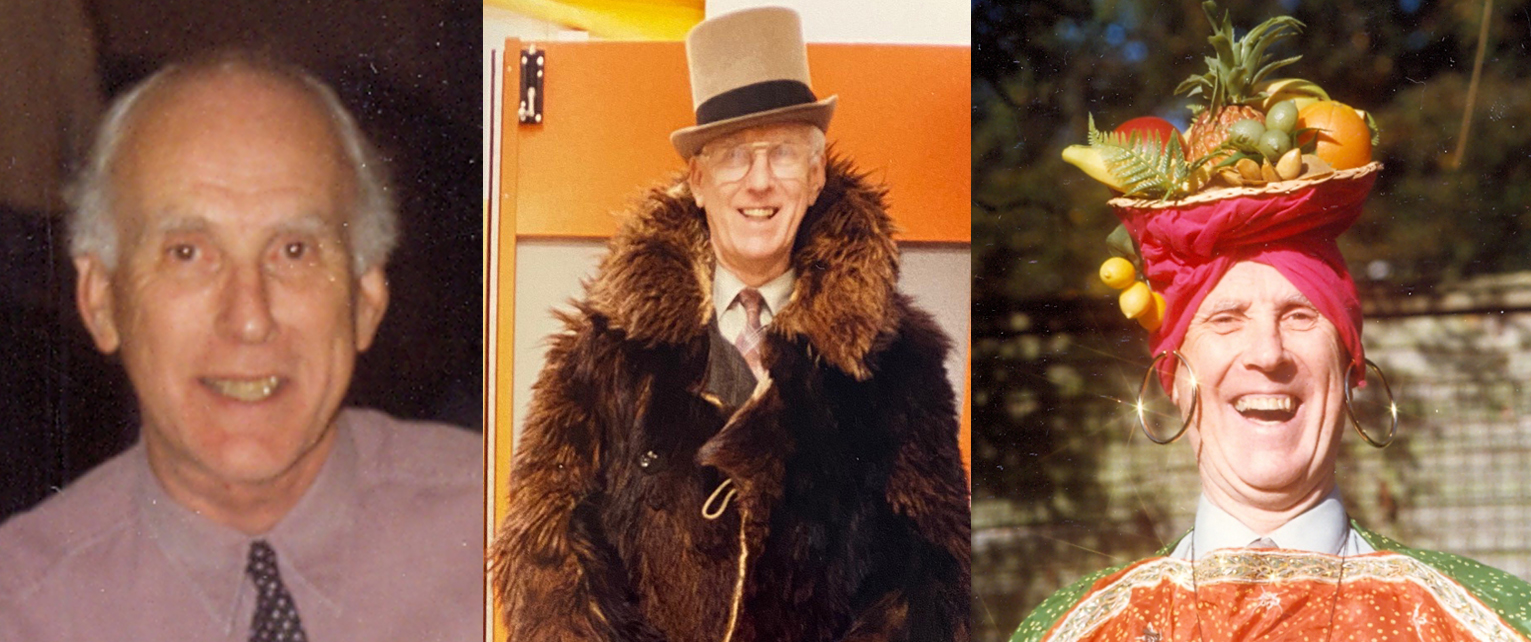

Photographs of Max Tyler. Left and right images courtesy of Alison Young, middle image from the Max Tyler Music Hall collection.

Max was often invited to speak at events all across the UK and frequently wrote articles for publications such as The Call Boy and The Stage, and was the editor of the journal Music Hall Studies. According to the Music Hall Studies website, it was Max’s belief that “if there were no other source relating to British social history for a long period around the turn of the nineteenth century, a study of music hall song would provide everything researchers were seeking”.

Max had been in talks with us for many years about his personal collection of music hall memorabilia and research, with him ultimately bequeathing it to the University. Sadly, Max passed away on 5th January 2018 after being in poor health for some time. In his obituary in The Call Boy, Roy Hudd said of Max, “Max Tyler, an old fashioned gentleman and an old fashioned gentle man”.

After his death we worked closely with the British Music Hall Society to transfer the collection to our archive.

Music Hall? What’s that!?

Music hall was an incredibly popular form of entertainment from the mid-19th through to the early 20th century. Originating in bars and public houses, it was a heady mixture of popular songs, comedy and variety entertainment.

From around 1850 specialist music halls began springing up all across the country as the genre became more and more popular. The patrons would smoke, eat and drink whilst enjoying the humorous (and often cheeky) performances from that night’s entertainers. These entertainers were the celebrities of the day, with the most successful ones, such as Marie Lloyd, performing both nationally and internationally. The songs they sang were often a comment on the working class social issues of the time, such as money troubles, overcrowded living, unfaithful or nagging spouses, and sometimes even true love!

As the 20th century progressed and World War loomed, music hall popularity dwindled. Then came radio, cinema, and later, television, firmly putting an end to its ubiquitous popularity.

The collection

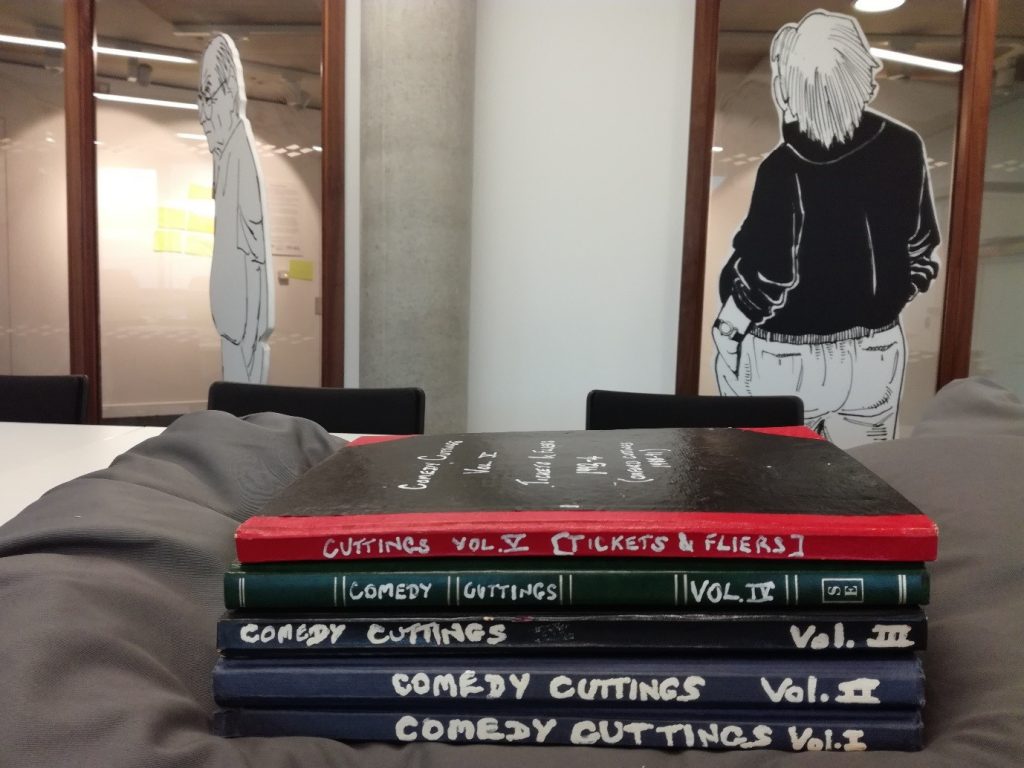

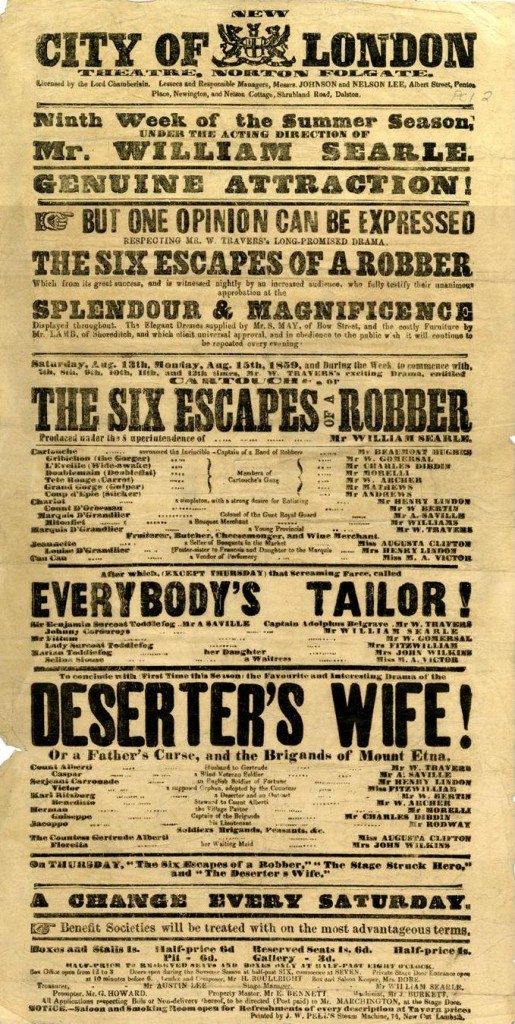

The Max Tyler Music Hall Collection is chock-full of music hall material, spanning from the late 19th century through to the early 21st century. It includes original and copies of Music Hall song sheets, sheet music and scripts for musical comedies, music hall programmes, playbills, 20th century music hall and vaudeville magazines and periodicals, music hall audio recordings on cassette, CD, shellac discs, and reel-to-reel tapes, published books on music hall, and music hall performers, Max’s research notes, and even Max’s very own stage blazer and hat!

We couldn’t possibly fit information about everything in the collection in to one blog post, so for today’s post we will focus on a couple of the larger elements of the collection.

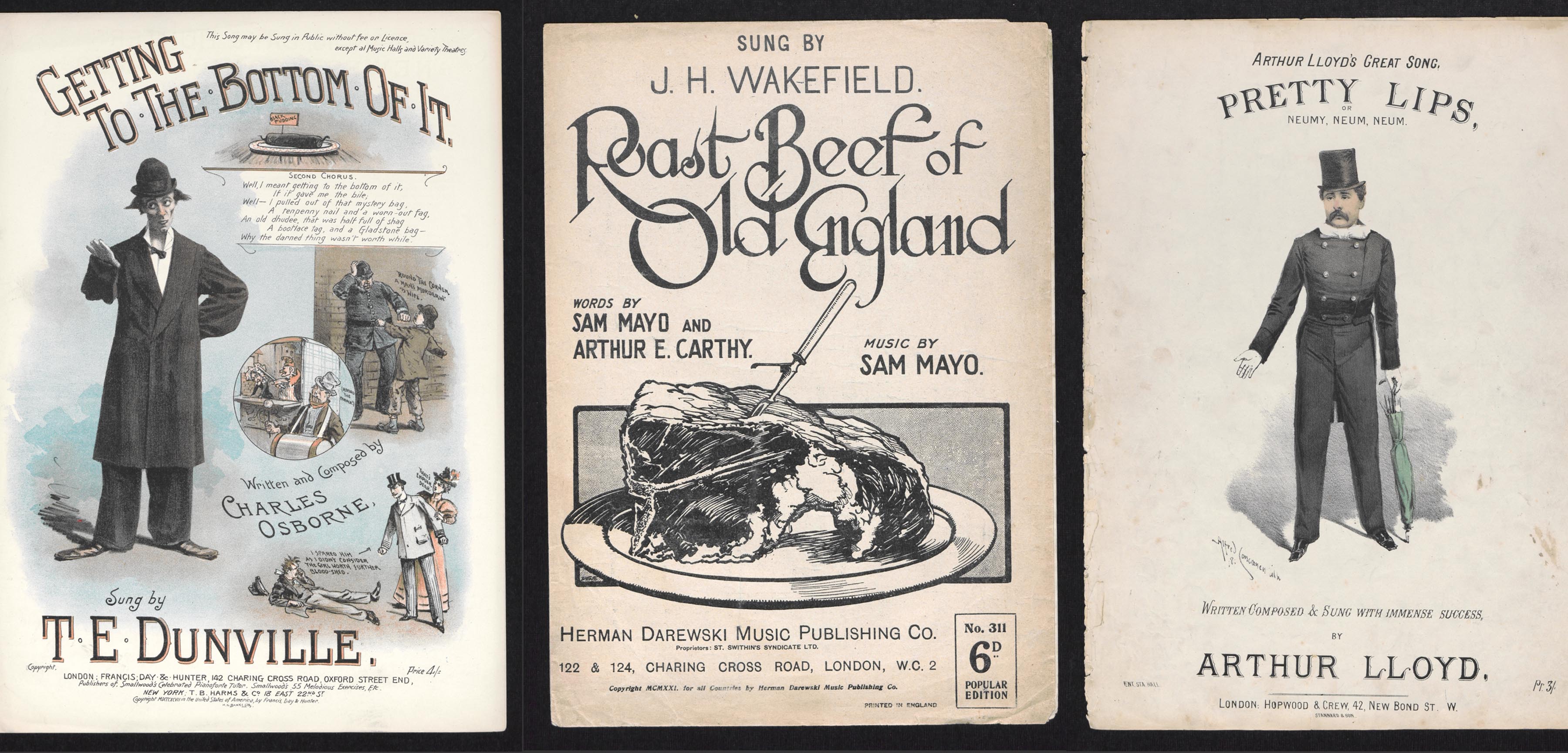

Songsheets

There are at least 1500 songsheets in the Max Tyler collection. With elaborately illustrated covers, and whimsical titles such as “I wasn’t so drunk as all that” and “La-Didily-Idily-Umti-Umti-Ay!” these songsheets are an incredible glimpse in to the working classes of the day (albeit a satirised, playful one!) Performers such as T.E. Dunville, Vesta Tilley, Marie Lloyd and Gus Elen, amongst many others, are represented, as well as prolific composers such as Joseph Tabrar, Arthur Lloyd and George Le Brunn.

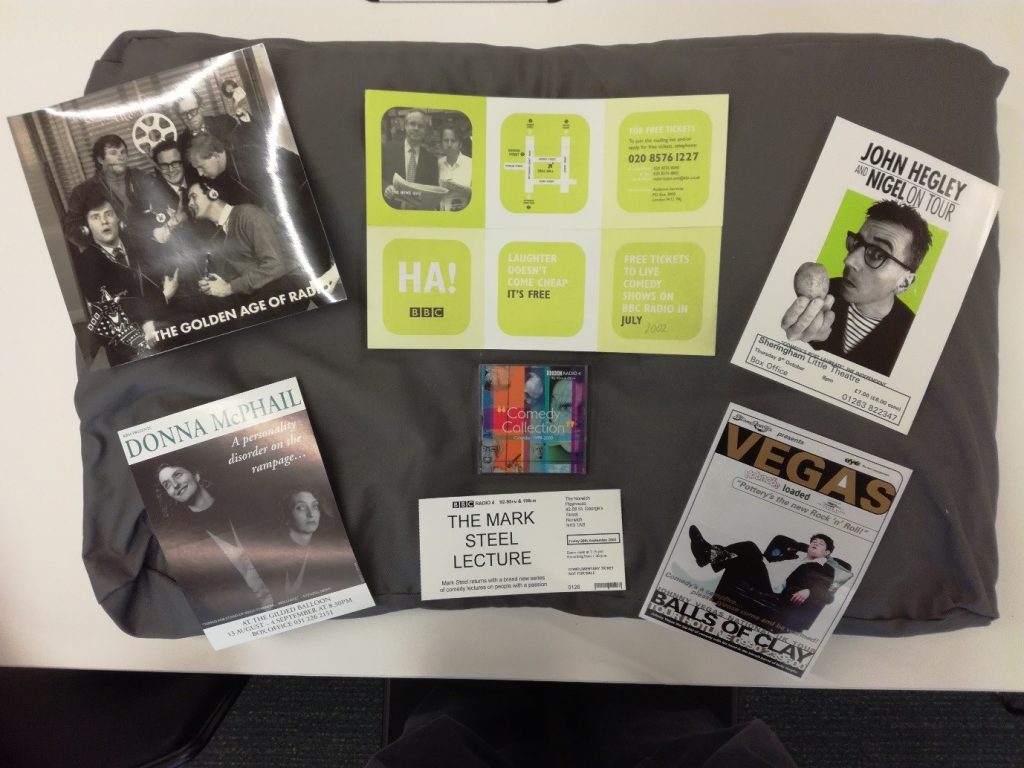

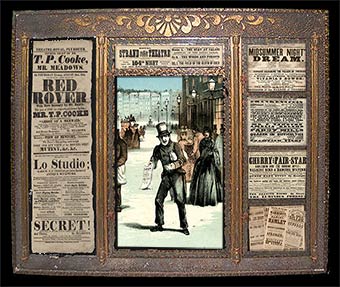

Programmes

The collection boasts beautifully illustrated late 19th and early 20th century programmes from variety theatres of the day, through to bold and photographic programmes of the later 20th century. It includes examples from provincial towns as well as the larger cities. This part of the collection is incredibly complimentary to our other theatre collections, which you can find out more about on our website!

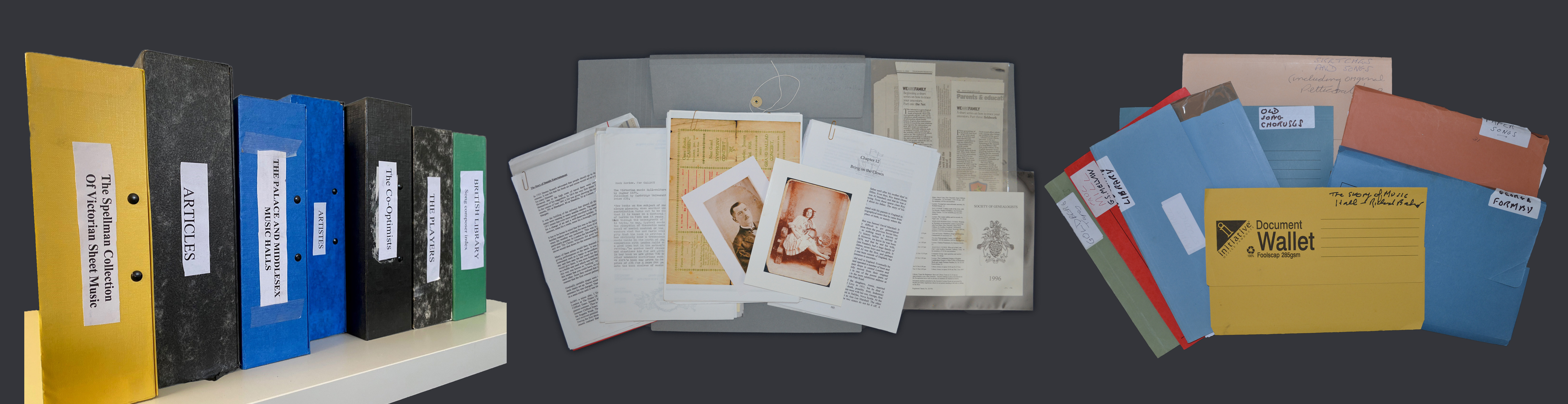

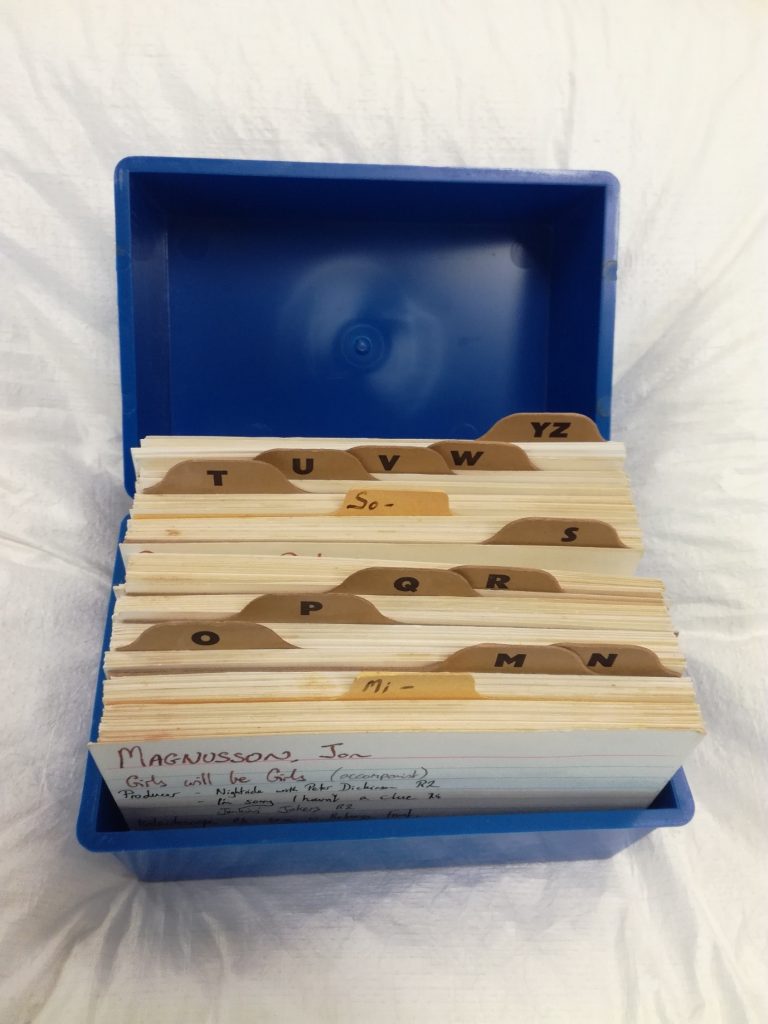

Research Notes

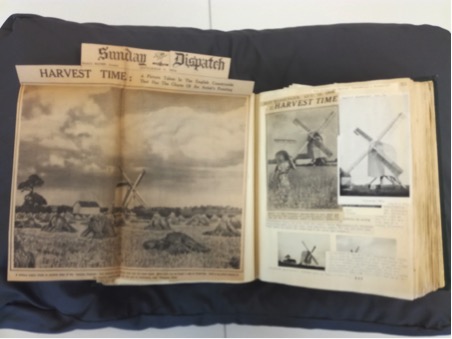

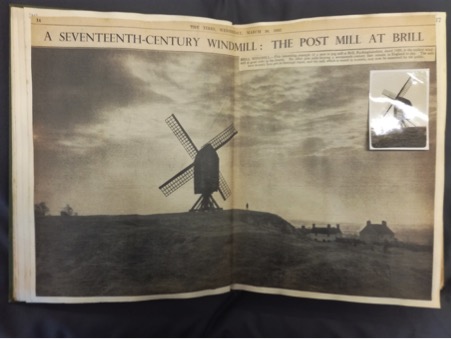

Max was a diligent organiser and avid researcher of music hall, the benefits of which can be seen in his collection. He would always go the extra mile when researching on behalf of the society or members of the public and seemed to have a knack for knowing where to look for the most elusive of details. There are over a hundred files in the collection, on topics from individual performers, composers and historic events, through to animals and trains; it if it was a theme in music hall then Max was bound to have researched it in some way!

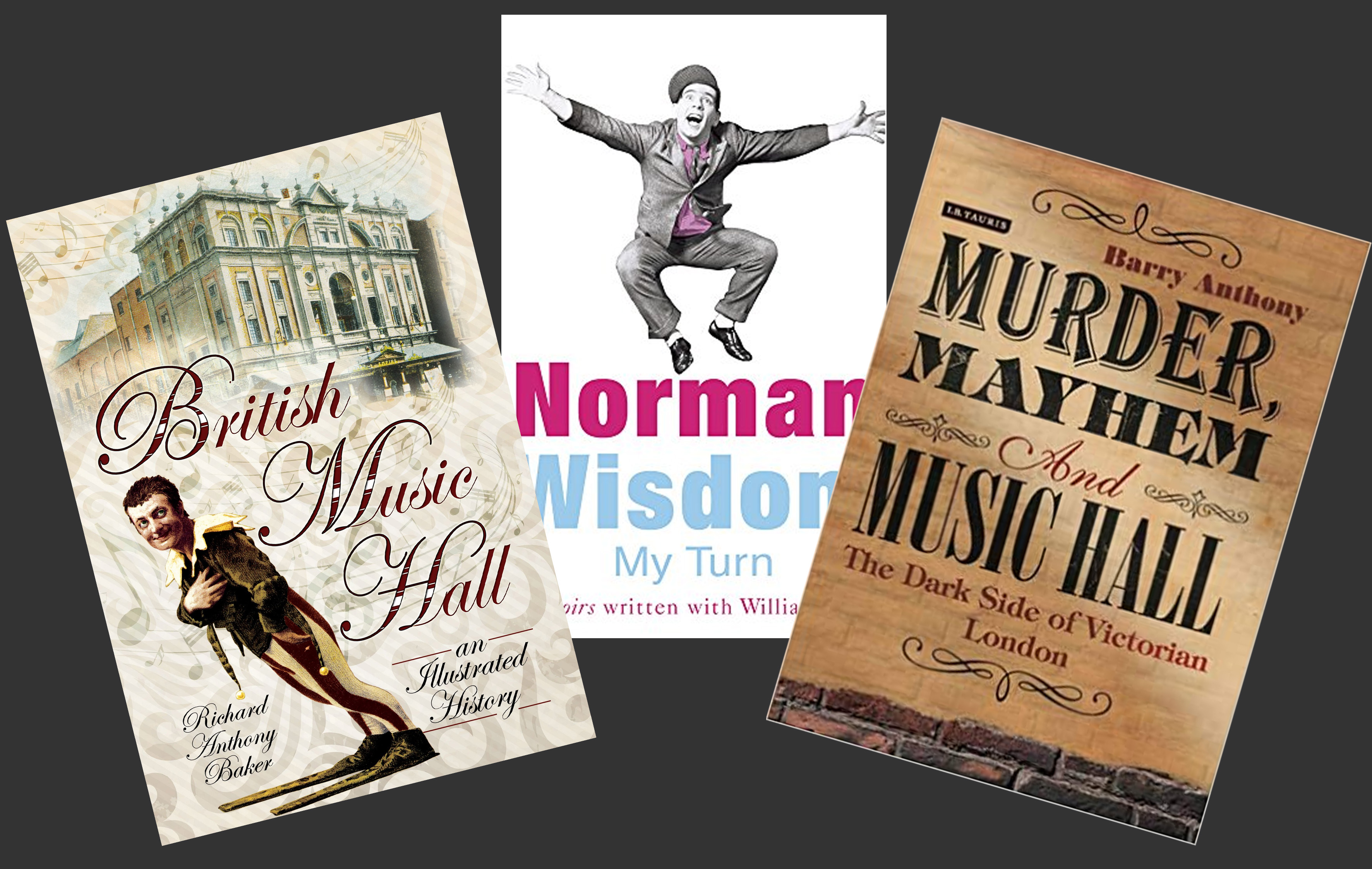

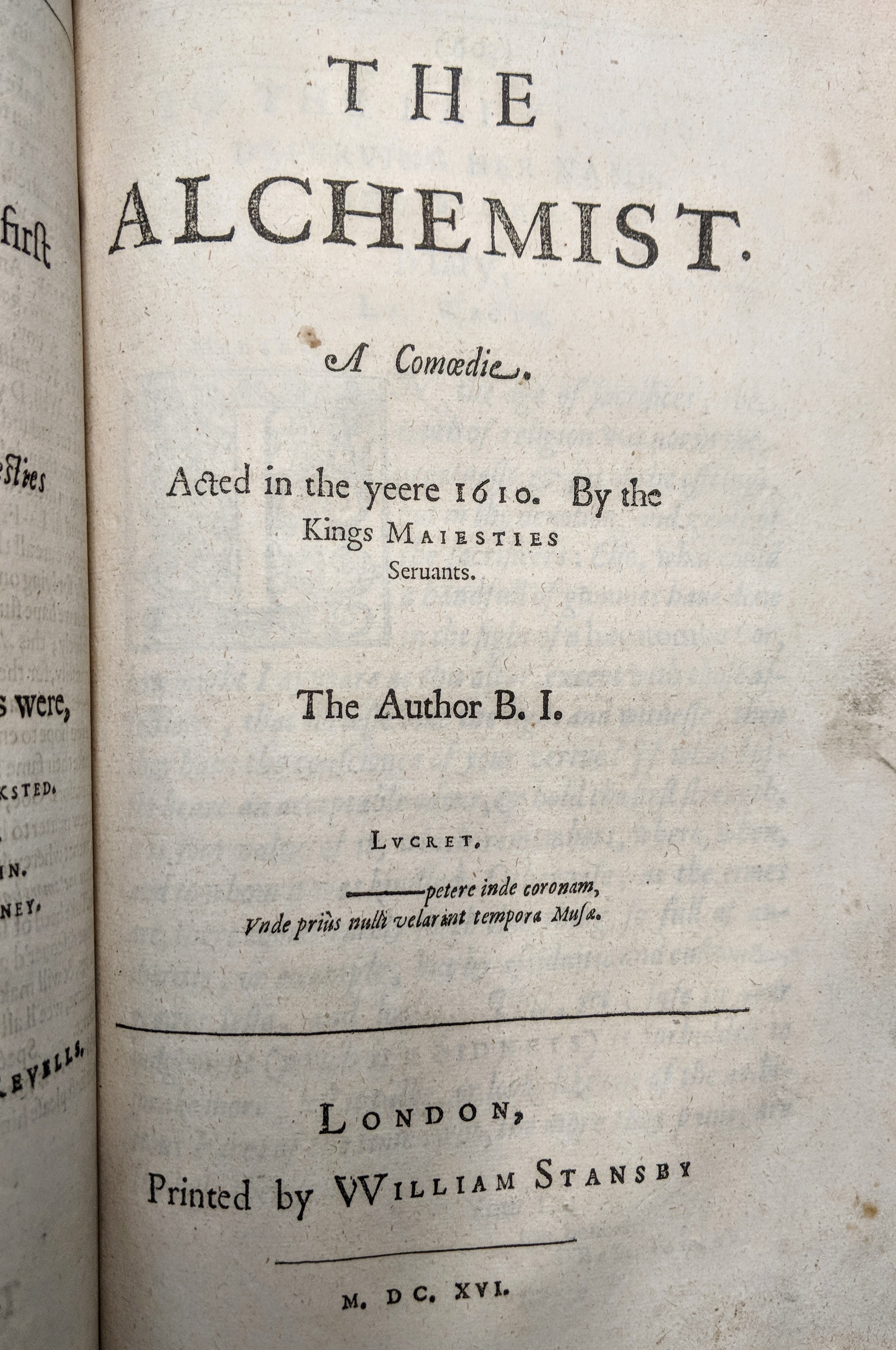

Book collection

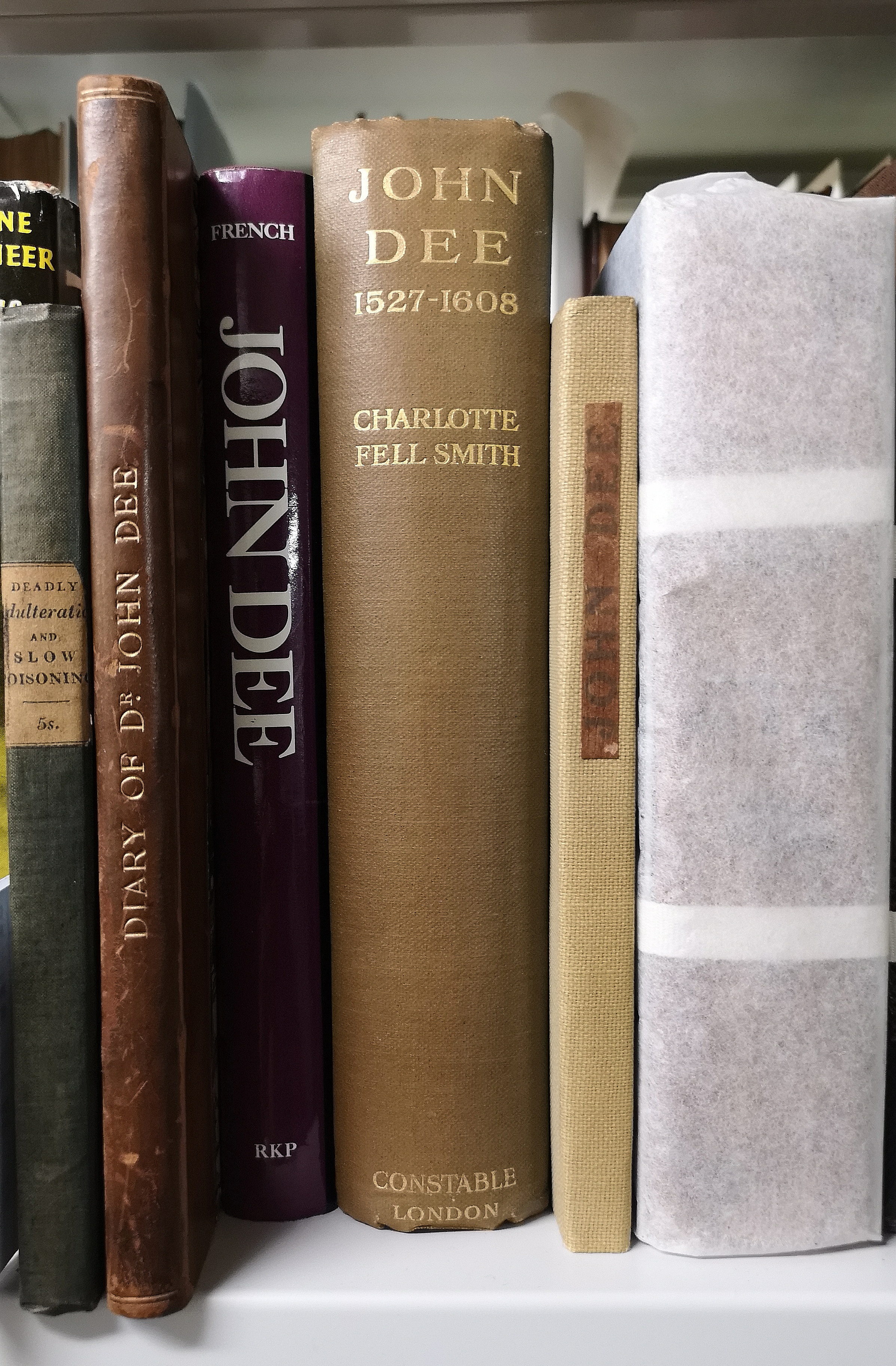

There are just under 550 books in Max’s collection. Again, the topics of these books vary from the specific to the peripheral when it comes to music hall. There are titles written by or about music hall performers, encyclopaedias and compendiums of music hall songs, stars and theatres, through to historical and literary texts.

We are currently working on organising and cataloguing the collection. Material which has been catalogued can be found here if you’re looking for archival material, or here if you’re looking for items from Max’s book collection.

If you are interested in researching or simply viewing any material from this stunning collection, please do get in touch with us via specialcollections@kent.ac.uk.