The book cataloguing for Rochester Cathedral has been going very well and has been a fairly smooth process to date, but sometimes a book presents itself that turns out to be a bit of an enigma. Sometimes it can be something small that stops you in your tracks for a short time, but on the odd occasion something bigger turns up, and the need to don a proverbial deer stalker hat whilst bearing a spy glass in one hand may indeed be necessary.

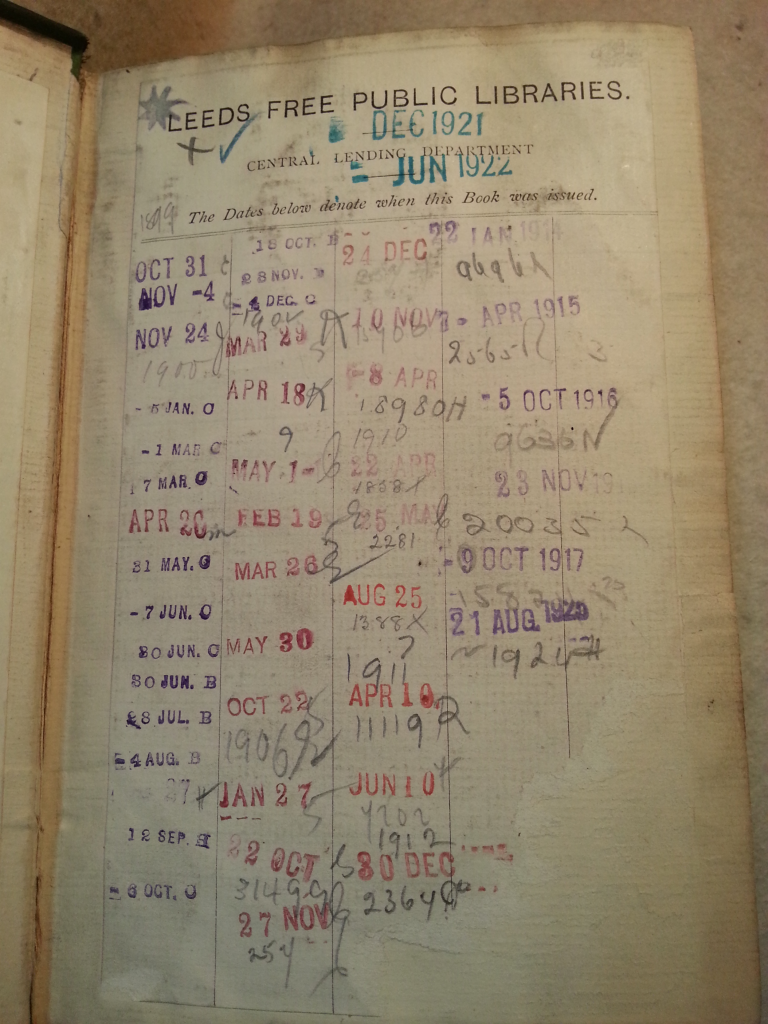

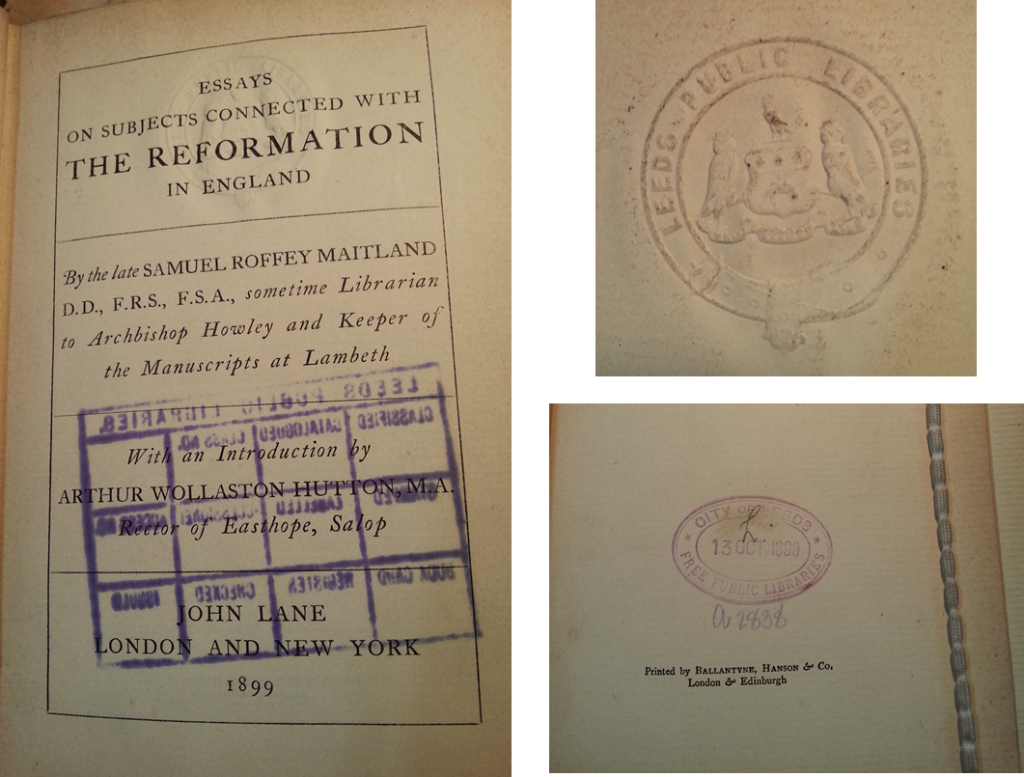

I always start, with every book that passes though my hands, by running a series of checks using a range of databases to find out if any other organisations or institutions hold the same copy. These organisations can range from universities from around the world, to libraries such as those at Lambeth Palace and the British Library. This not only helps me to work out if the copy I have in front of me is what I think it is, which is especially useful when my book lacks a date of publication, but also allows me to see if my copy has any unique attributes, such as bindings that vary from other copies or editions. This is for the most part a successful process.

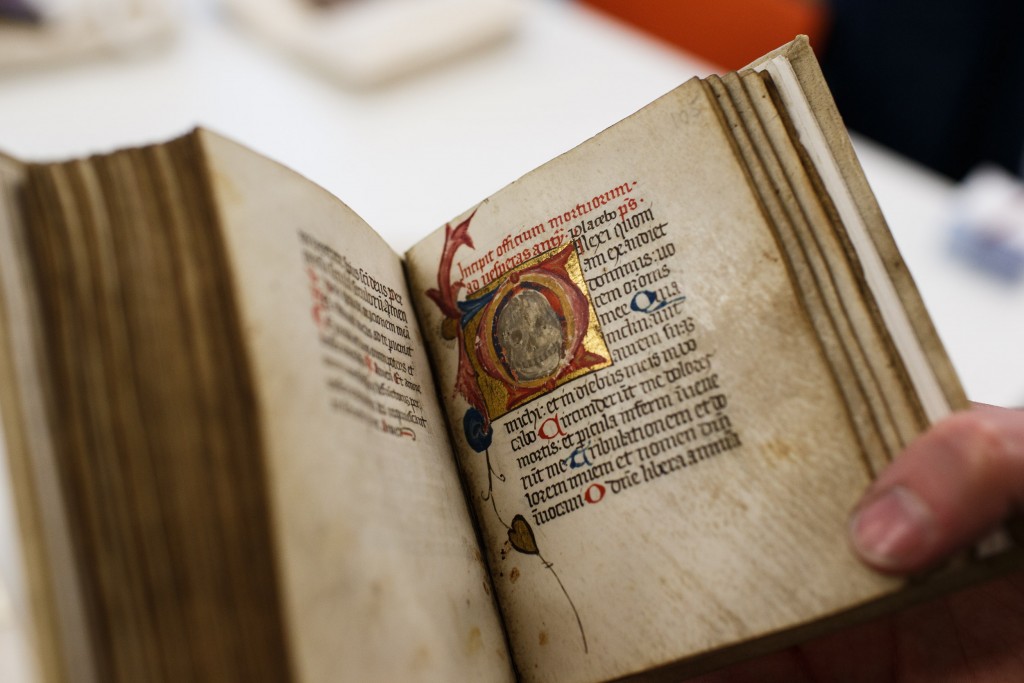

However, the problem with rare book cataloguing is that the book I am looking for isn’t always available anywhere else. They are not always held by other institutions and are not held on any of my usual ‘go-to’ databases. Even my back-up checks of auction houses fail to generate results in some cases. This is never a huge problem as I tend to be able to work with what I have in front of me, until I met this inconspicuous little number.

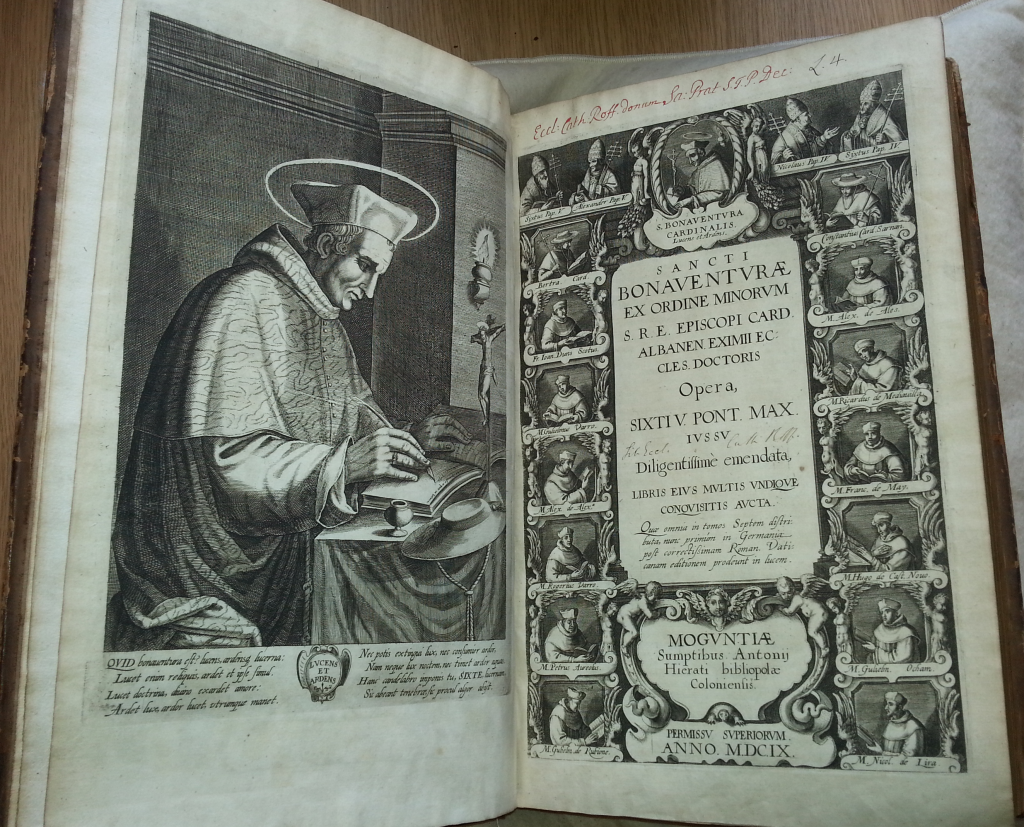

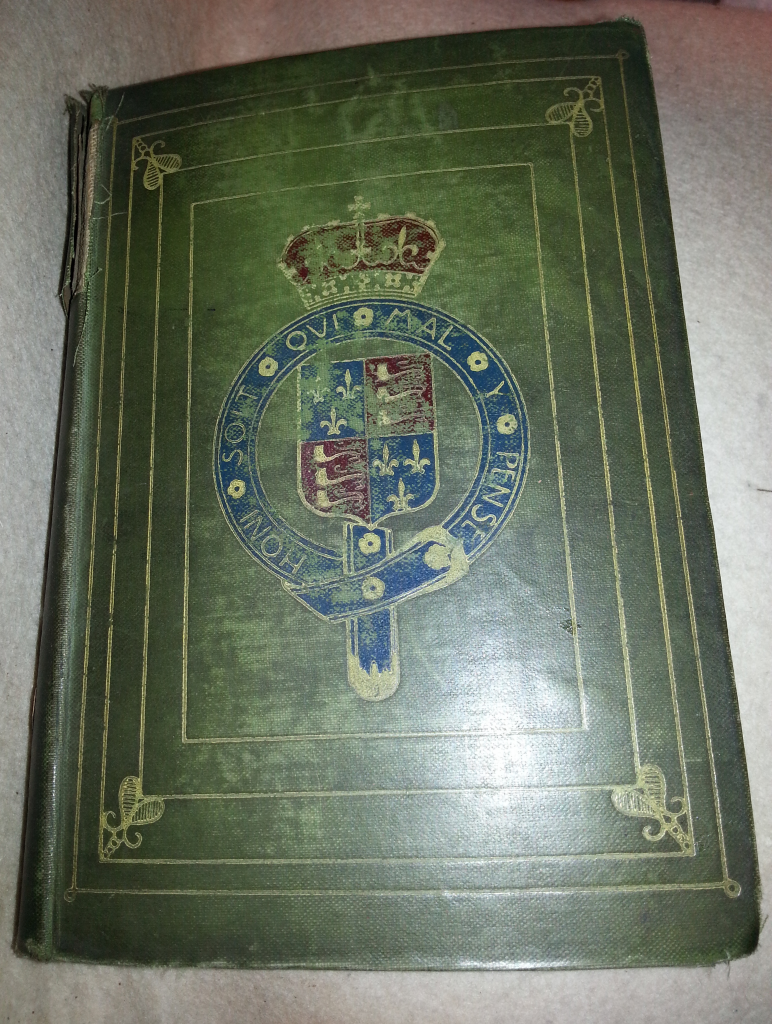

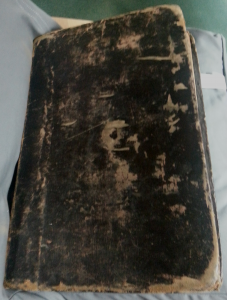

From the outside it offers very little in the way of aesthetically pleasing design or any clues as to what may lay within. It is somewhat plain and quite unremarkable in appearance, particularly when compared to other ornate bindings within the collection.

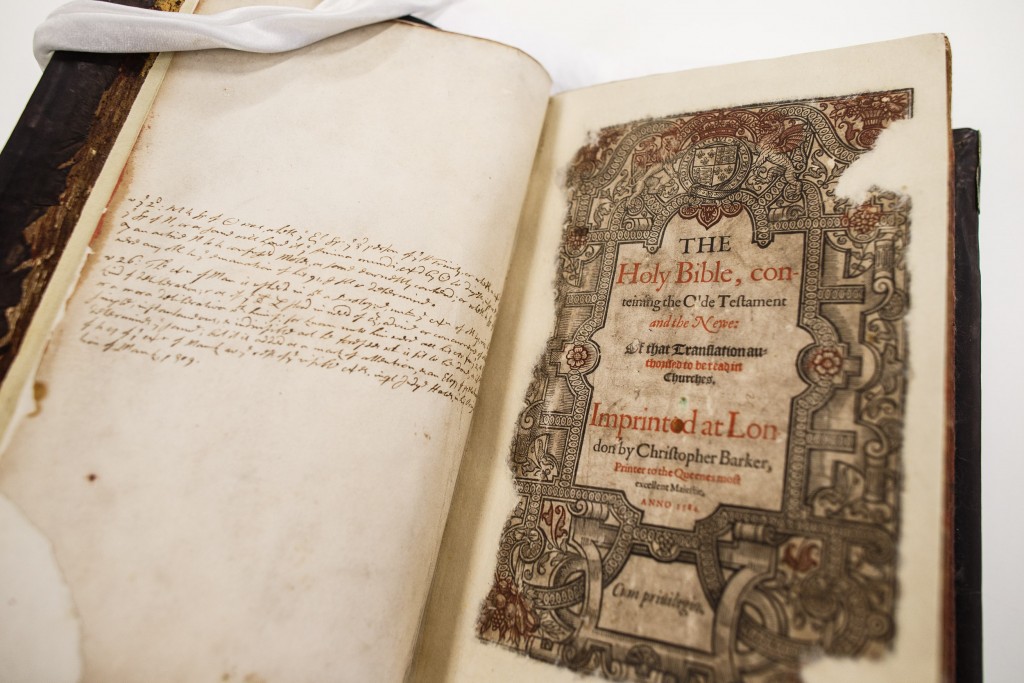

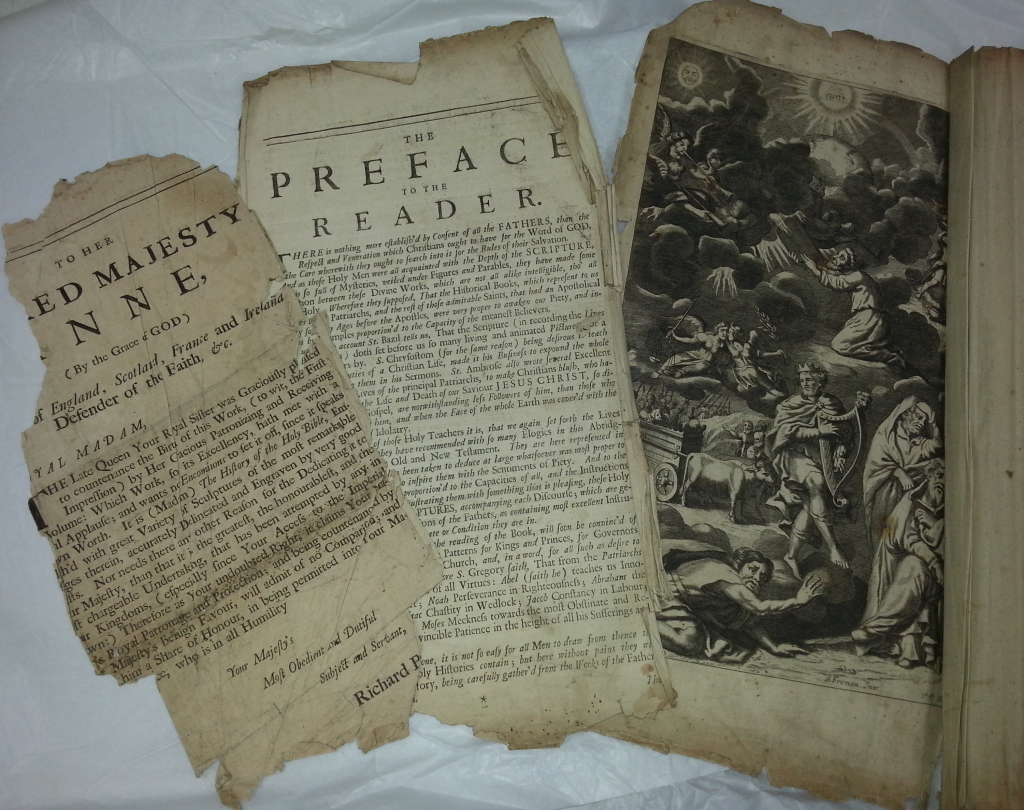

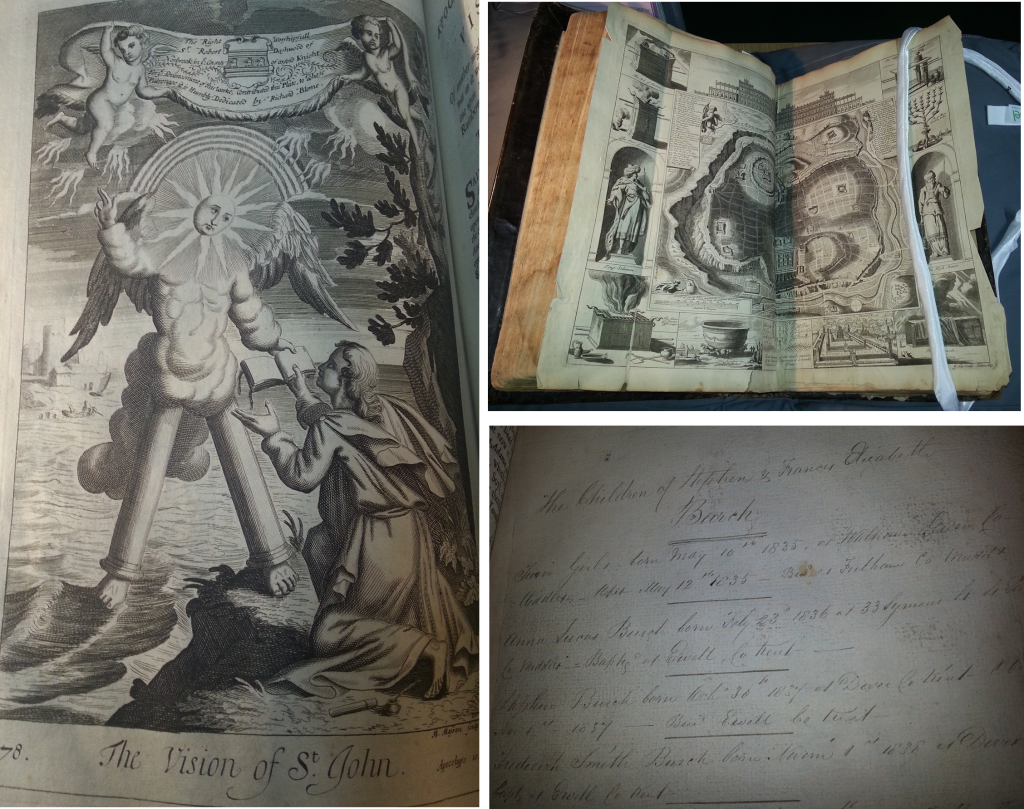

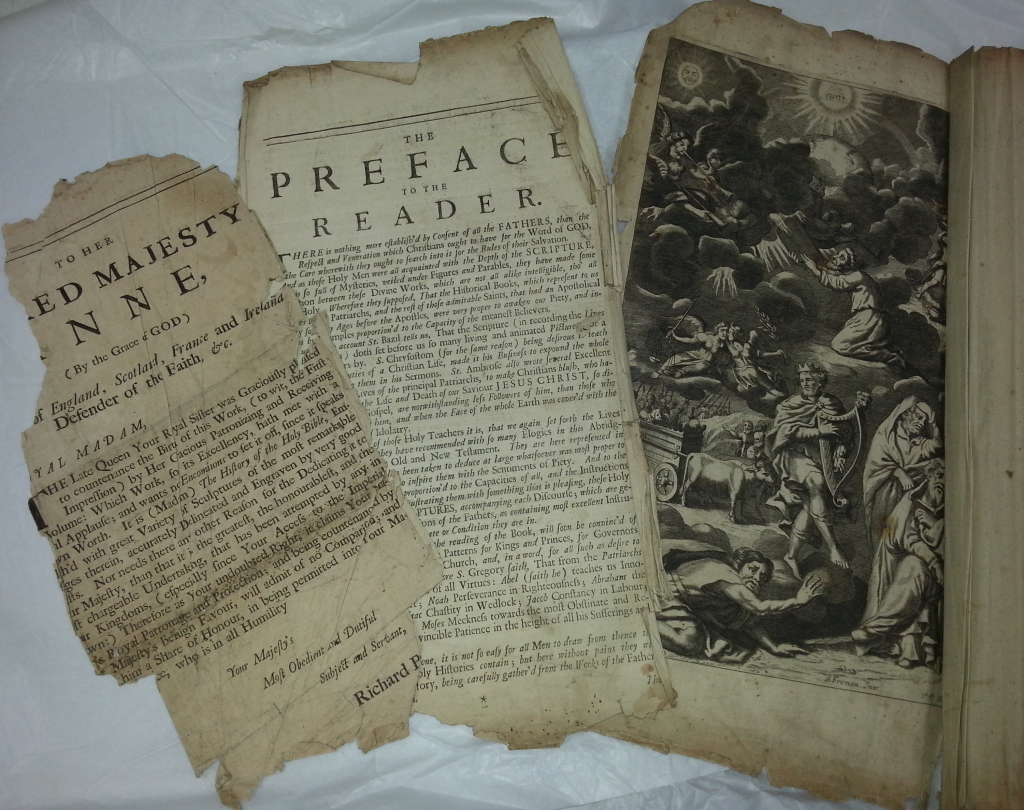

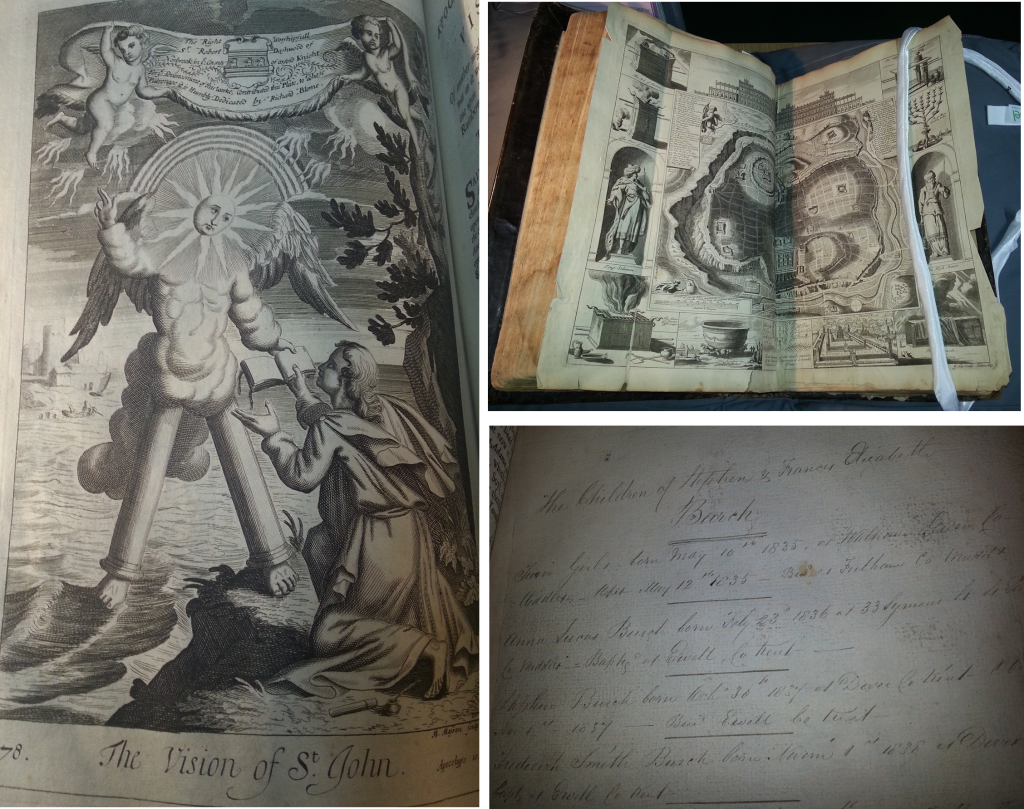

I opened the front cover not expecting anything out of the ordinary, and was greeted by what appeared to be a dedication to Her Majesty Queen Anne, as well as a preface to the reader and an engraving. Not an unusual grouping of items in themselves, but where was the title page?

Finding a place to start was going to be difficult, but I had to start somewhere. After checking the entire book for supplementary title pages (of which there were none), I began reading the text within the first two pages to look for clues as to what this book may be.

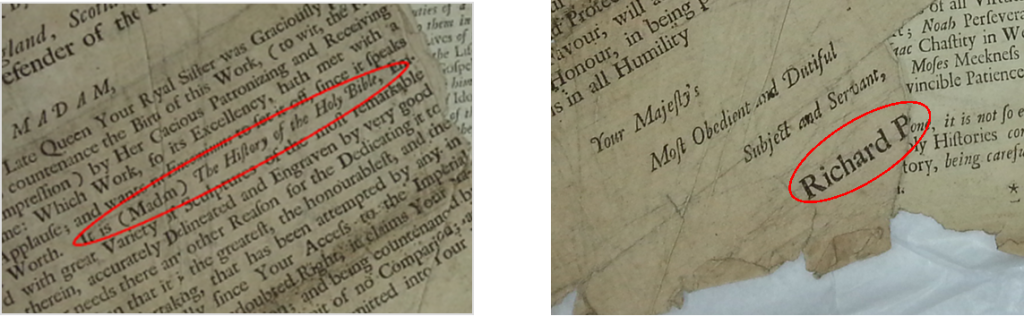

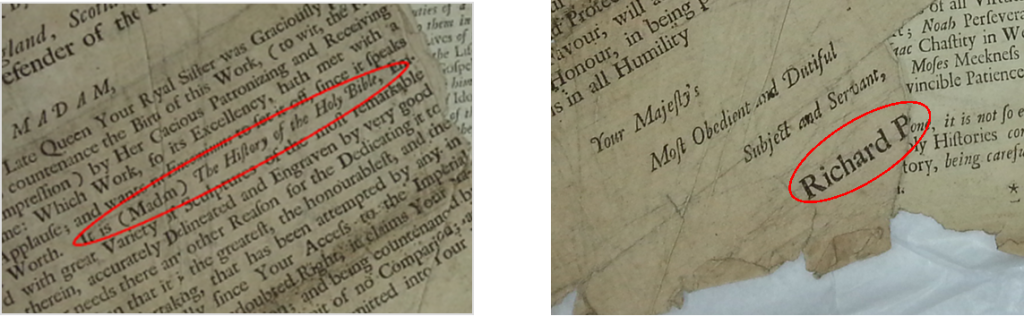

My first clue came from the dedication to Queen Anne. One sentence stated that “It is (Madam) The History of the Holy Bible.” I also noted that the dedication was signed by Richard P…. so kept in mind that this was most likely going to be the author or publisher of the work.

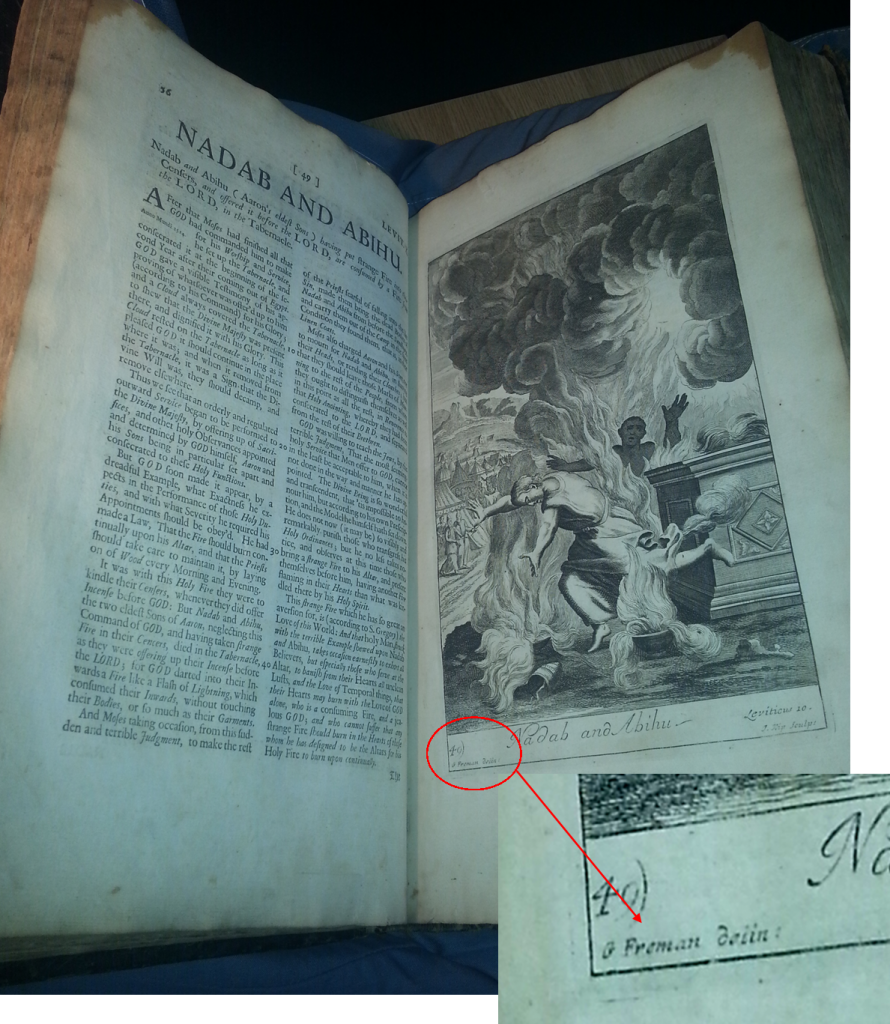

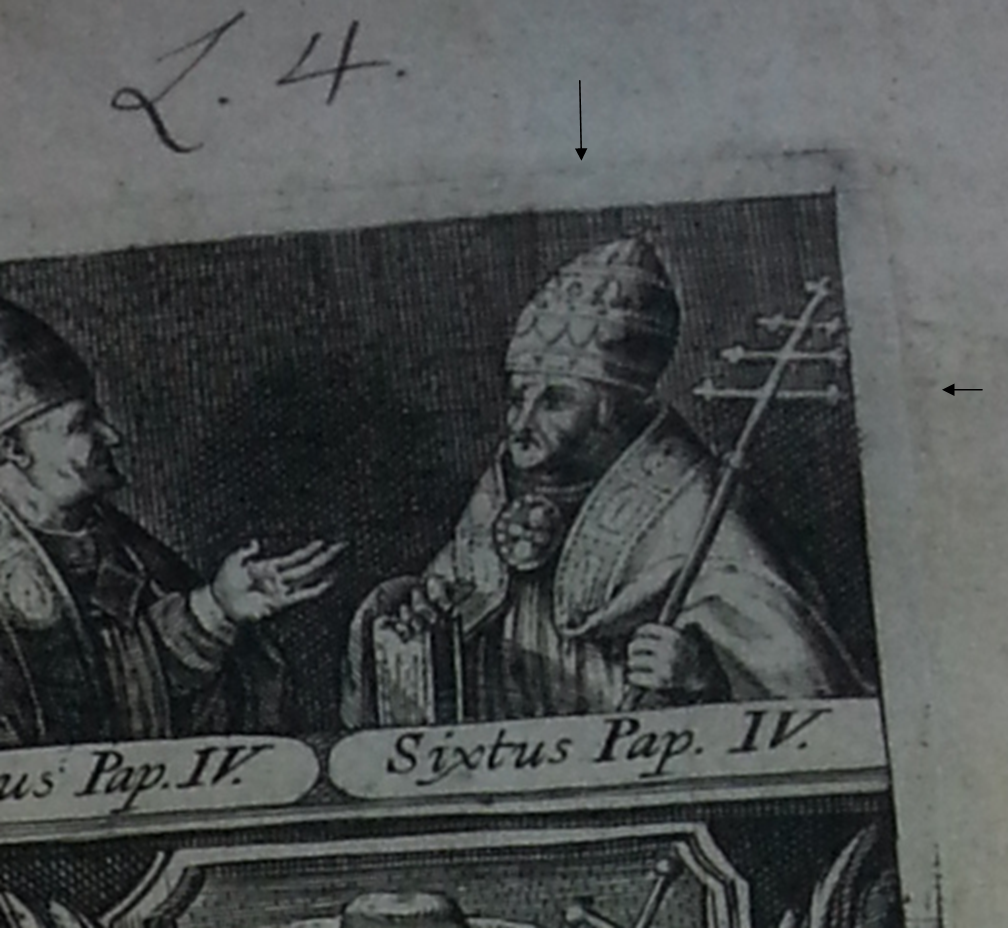

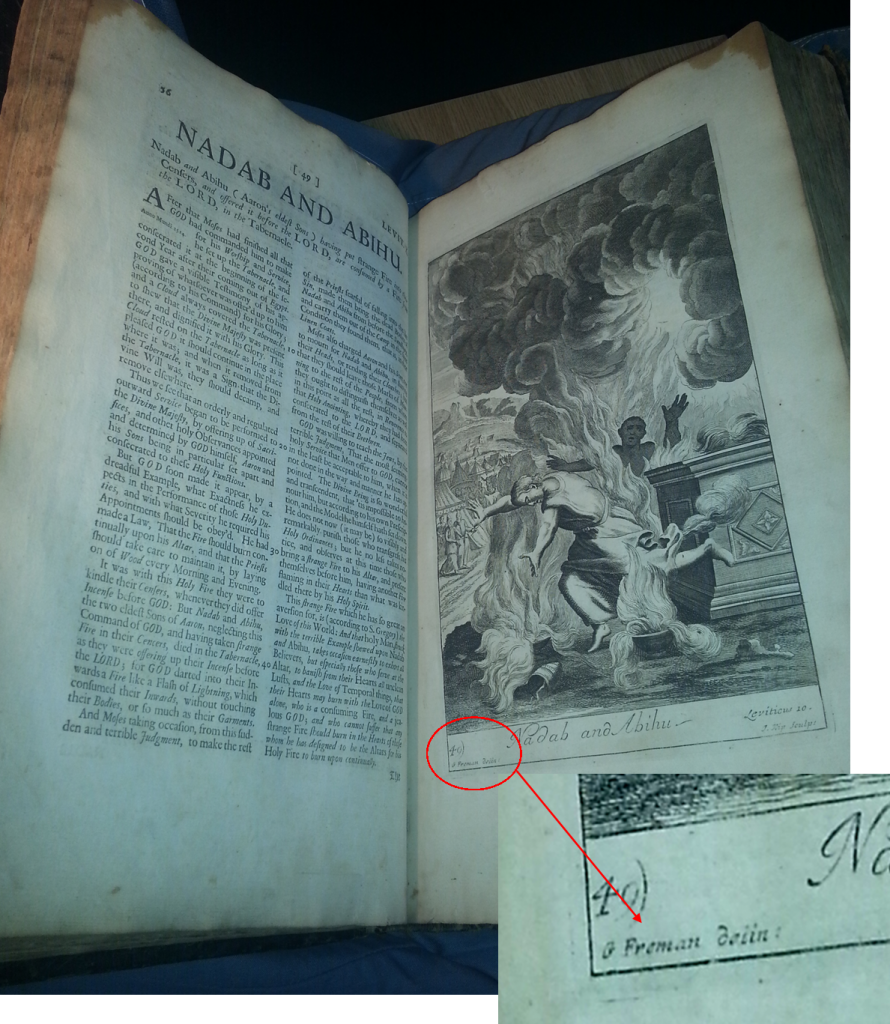

I started exploring all the usual databases and uncovered a few close matches, but nothing concrete. As a cataloguer, my need to source the most accurate information available needs to be satisfied before I share it with the world. So, although still lacking the full knowledge as to the definite identity of this book, I set off on a page by page exploration. This text is very fortunately full of Biblical images created by a range of well known engravers. This, I hoped, would help me on my way to discovering the true identity of the text, and to start building a catalogue record containing the details of every single engraver with responsibility for one of these beautiful illustrations.

This process helped me to identify nine engravers. Although I still lacked the title, author and publication, it was a reliable start.

I then worked on building a catalogue record where the information I could source about my book was easily available. Sometimes even the simplest of details, such as how the page numbers are structured within the text (which isn’t always straight forward with rare books), can help in identifying a particular edition or imprint of a publication.

I was well on my way to completing my record. I’d referenced everything from the page numbers and subject matter, to the condition of the item, its binding, provenance and the presence of any inscriptions and signatures. But still without a title, I returned to the drawing board, optimistic that my metadata was sufficient to cross-reference with my favorite data sources. I used the information that I had gathered so far and started my search once more. Here I had a breakthrough and sourced several versions of the same title, ‘The history of the Old and New Testament extracted out of sacred Scripture and writings of the fathers‘ by Nicholas Fontaine, and was delighted with this discovery. However, I needed to establish if it was indeed the given title and if so, which edition.

I headed over to EBBO (Early English Books Online) to view their digitised content of rare books. Here I found five potential matches, but after thorough checking I concluded that these were not exactly the same in every way (variant dedication, note to the reader and frontispiece image). However, I had concluded that the above title was correct in its basic form and that this would be sufficient for my catalogue record. I also had an author I was certain was correct.

My record was almost complete. However, one mystery remains even to today. When was it published and who published it? Because I’ve not been able to source any absolute confirmation that my copy is exactly the same as any other copy, it would be inappropriate to rely on other sources for the name of potential publishers,booksellers, or a date of publication. To overcome this, the best that can be done is to calculate the likely date of publication based on all other evidences, ensuring this is appropriately referenced as an estimated date in the catalogue record.

For the most part, the majority of the books within this collection have had in tact title pages, making life much easier from the cataloguing perspective. But becoming a detective for a while adds another level of interest to the job. When you love rare books as much as I do, getting to discover more along the way that you wouldn’t have otherwise encountered is an added bonus.