Posted by Sarah

Our first post-screening discussion after the lengthy Summer Break was lively, and encompassed several areas relating to melodrama, this specific film and Bette Davis. It included comment on: Bette Davis’ performance; the film as an adaptation of Somerset Maugham’s novel; the film’s music; comparison of the female characters; later adaptations of the novel; stars Leslie Howard and Bette Davis’ other work together; Somerset Maugham as a writer.

Unsurprisingly the discussion began with comments on Davis’ tour de force performance. Davis’ ability to convey Mildred Rogers’ attempts to appear more refined through her voice was deemed especially effective. She shifted effortlessly, and at the appropriate moments, between strangulated cockney and strangulated cockney with a slight hint of unconvincing cultivation. This undulating movement was also present in Davis’ physical performance. This was quite exaggerated. Using gestures and facial expressions liberally, Davis wonderfully conveyed both Mildred’s flirtatious nature and her at times pointedly indifferent attitude to Philip. We especially noted Davis’ use of  her eyes to express these contradictory aspects of Mildred’s character. Occasionally Mildred with her head tipped down, steadily and flirtatiously looked up at Philip across the top of her champagne glass (see picture on right). More often though, she flicked her eyes away from him, either quickly or slowly, to signal her disagreement with him or to reveal that she was mulling over an offer he had made.

her eyes to express these contradictory aspects of Mildred’s character. Occasionally Mildred with her head tipped down, steadily and flirtatiously looked up at Philip across the top of her champagne glass (see picture on right). More often though, she flicked her eyes away from him, either quickly or slowly, to signal her disagreement with him or to reveal that she was mulling over an offer he had made.

Despite the fact that throughout the film Davis employed theatrics, and could hardly be described as restrained, her two big scenes were stunningly effective. In Mildred’s tirade against Philip, which we discussed at length, Davis ratcheted her performance up a gear. There is constant movement in this scene. Both by Davis, who turns to and away from the camera whilst striding away from it, and by the camera itself which follows Davis at some speed. Extra impetus was added by the fact that the scene was fairly quiet up to this point. It was also the first time we saw Mildred really furious. This was prompted by Philip’s comment that Mildred disgusts him. This, in turn, was in response to her attempt to seduce him. After repeating Philip’s words with her voice and body shaking with disbelief and anger, the scene reaches its climax as Davis performs a violent gesture. She tells Philip that every time he has kissed her she wiped her mouth. Mildred clearly thinks this is a useful phrase to torment Philip with, and she repeats it, at

Despite the fact that throughout the film Davis employed theatrics, and could hardly be described as restrained, her two big scenes were stunningly effective. In Mildred’s tirade against Philip, which we discussed at length, Davis ratcheted her performance up a gear. There is constant movement in this scene. Both by Davis, who turns to and away from the camera whilst striding away from it, and by the camera itself which follows Davis at some speed. Extra impetus was added by the fact that the scene was fairly quiet up to this point. It was also the first time we saw Mildred really furious. This was prompted by Philip’s comment that Mildred disgusts him. This, in turn, was in response to her attempt to seduce him. After repeating Philip’s words with her voice and body shaking with disbelief and anger, the scene reaches its climax as Davis performs a violent gesture. She tells Philip that every time he has kissed her she wiped her mouth. Mildred clearly thinks this is a useful phrase to torment Philip with, and she repeats it, at increased volume. Davis also emphasises the point by ferociously rubbing her arm across her heavily lipsticked mouth. It is notable that while the gesture is arguably one of the film’s most memorable moments, partly due to Davis’ heightened performance, it does not appear in the novel.

increased volume. Davis also emphasises the point by ferociously rubbing her arm across her heavily lipsticked mouth. It is notable that while the gesture is arguably one of the film’s most memorable moments, partly due to Davis’ heightened performance, it does not appear in the novel.

What made it unforgettable is that as Mildred is shouting angrily with mad, staring eyes, she is also smiling, or perhaps more correctly, grimacing. She clearly relishes having the opportunity to express her true feelings to Philip. This was compared to other moments in Davis films when her characters’ real self is unleashed, for example In This Our Life (1942, John Huston).

Davis’ other ‘big’ scene revealed more of Mildred’s vindictiveness. This is very possibly even worse than her spontaneous reaction to Philip’s comment as she has had time to consider her actions. She gleefully rampages through Philip’s apartment, destroying the works of art which mean the most to him, but which she has declared she finds vulgar.The music which accompanies the following scene is revealing. Mildred coolly picks up ‘baby’ from her cot in preparation of them both leaving Philip’s apartment. There is a ‘frowsy’, almost comedic, quality to the music. While the audience has never entertained the same illusions about Mildred as Philip has, it suggests that after her tirade and the following rampage the film is now signalling through music that her real nature is indeed shabby. It was mentioned that apparently after the first screening of the film, some of its music was changed as it was considered too comedic in places.

Our focus on performance, and in particular specific moments of heighted emotion and gesture was related to some of the discussion we engaged in at our previous screening sessions. Of special interest, and worthy of further consideration, is how these instances are juxtaposed with elements of restraint.

As with some of our previous discussions, we spoke about the suffering woman. While the film showcased Davis’ performance, it was perhaps less about Mildred’s suffering than Philip’s. This is similar to the source novel. Much of its 700 pages detailed Philip’s childhood, his time spend living abroad, his medical training and his later search for employment. Unsurprisingly the 83 minute film dispensed with much of the novel’s plot. The fact it chose to focus on Philip and Mildred as its main characters was testament to the pernicious effect Mildred had on Philip and clearly related to Hollywood’s privileging of the romantic couple.

As with some of our previous discussions, we spoke about the suffering woman. While the film showcased Davis’ performance, it was perhaps less about Mildred’s suffering than Philip’s. This is similar to the source novel. Much of its 700 pages detailed Philip’s childhood, his time spend living abroad, his medical training and his later search for employment. Unsurprisingly the 83 minute film dispensed with much of the novel’s plot. The fact it chose to focus on Philip and Mildred as its main characters was testament to the pernicious effect Mildred had on Philip and clearly related to Hollywood’s privileging of the romantic couple.

Philip’s other romantic relationships

Philip’s other romantic relationships  (with Norah, played by Kay Johnson, left, and Sally, played by Frances Dee, right) were given little screen time, not really enough to compete with Mildred’s central position. The female characters and performances other than Mildred/Davis were very restrained. Other characters (such as Dr Jacobs, the medical student Griffiths and especially the flamboyant Athelny) were sketched more broadly. We thought these characterisations probably lacked depth because they were given very little time to make their impression. It is perhaps also telling that these are all played by male actors – Desmond Roberts, Reginald Denny and Reginald Owen respectively. While the performance styles differ to the lesser female characters, they also supply contrast to Davis and Howard’s more nuanced portrayals.

(with Norah, played by Kay Johnson, left, and Sally, played by Frances Dee, right) were given little screen time, not really enough to compete with Mildred’s central position. The female characters and performances other than Mildred/Davis were very restrained. Other characters (such as Dr Jacobs, the medical student Griffiths and especially the flamboyant Athelny) were sketched more broadly. We thought these characterisations probably lacked depth because they were given very little time to make their impression. It is perhaps also telling that these are all played by male actors – Desmond Roberts, Reginald Denny and Reginald Owen respectively. While the performance styles differ to the lesser female characters, they also supply contrast to Davis and Howard’s more nuanced portrayals.

Some of the film’s more avant garde touches were also discussed. We noted the straight-to-camera acting of Davis and Howard in particular, during which eyelines did not match and the 180 degree rule was violated. The film’s ending which shows Philip and Sally crossing a busy street was deemed particularly odd. We presume that Philip is telling Sally of Mildred’s death, and the fact he is now free, but the unnecessarily loud traffic noise drowns out the dialogue. There did not seem to be any real reason for this, especially as we had already seen Davis at her most unglamorous as the dying Mildred was collected from her room and taken to hospital.

There was also a dreamlike quality to much of the film, not just during the projection of  Philip’s dreams. The latter afforded a greater opportunity for Davis to display her acting skills as in these Mildred is far more responsive to Philip, especially facially. In his dreams Philip imagines Mildred speaking with Received Pronunciation. As the ‘real’ Mildred, Davis shows Mildred’s doomed attempts to achieve this accent. This is revealing of Philip’s prejudices and it is also notable that in the dream sequences his physical disability has disappeared. This split between reality and dream also effectively highlights the unusual social realism of the film and Hollywood’s usual focus on the glamour of coupledom and romance.

Philip’s dreams. The latter afforded a greater opportunity for Davis to display her acting skills as in these Mildred is far more responsive to Philip, especially facially. In his dreams Philip imagines Mildred speaking with Received Pronunciation. As the ‘real’ Mildred, Davis shows Mildred’s doomed attempts to achieve this accent. This is revealing of Philip’s prejudices and it is also notable that in the dream sequences his physical disability has disappeared. This split between reality and dream also effectively highlights the unusual social realism of the film and Hollywood’s usual focus on the glamour of coupledom and romance.

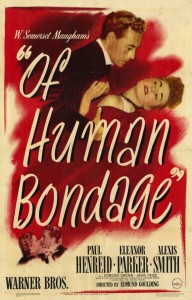

We wondered about later versions of the story. In 1946 Paul Henreid (Davis’ co-star in Now Voyager 1942 and Deception 1946) and Eleanor Parker starred in a Hollywood remake directed by Edmund Goulding (who often collaborated with Davis). Kim Novak and Laurence Harvey starred in the 1964 UK film (see a clip of Mildred’s death scene: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N8iVYV93BYw). Interestingly this was written by Bryan Forbes and partly directed by him (uncredited) alongside the UK’s Ken Hughes and Hollywood’s Henry Hathaway. Forbes is known for his kitchen sink drama The L Shaped Room in 1962.

We wondered about later versions of the story. In 1946 Paul Henreid (Davis’ co-star in Now Voyager 1942 and Deception 1946) and Eleanor Parker starred in a Hollywood remake directed by Edmund Goulding (who often collaborated with Davis). Kim Novak and Laurence Harvey starred in the 1964 UK film (see a clip of Mildred’s death scene: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N8iVYV93BYw). Interestingly this was written by Bryan Forbes and partly directed by him (uncredited) alongside the UK’s Ken Hughes and Hollywood’s Henry Hathaway. Forbes is known for his kitchen sink drama The L Shaped Room in 1962.

This highlights further melodrama and British social realism’s connections, mentioned in last term’s discussion on Love on the Dole (1941).

TV adaptations were made in a 1949 episode of Studio One starring Charlton Heston and Felicia Montealegre (watch the whole episode here:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=klGfU5VKGAc) and as part of Somerset Maugham TV Theatre in 1952. Cloris Leachman appeared as Mildred.

We also discussed Howard and Davis’ other films together. They appeared in The Petrified Forest (1936) and It’s Love I’m After (1937) – both directed by Archie Mayo. While the former could also be described as a melodrama, a gangster melodrama, the latter is a light romantic comedy in which Howard and Davis play a bickering couple. Performance is central to this film too, however as their characters are actors. (Do take a quick look on www.youtube.com for clips and trailers.)

We also discussed Howard and Davis’ other films together. They appeared in The Petrified Forest (1936) and It’s Love I’m After (1937) – both directed by Archie Mayo. While the former could also be described as a melodrama, a gangster melodrama, the latter is a light romantic comedy in which Howard and Davis play a bickering couple. Performance is central to this film too, however as their characters are actors. (Do take a quick look on www.youtube.com for clips and trailers.)

Discussion ended with brief mention of the critical evaluation of Maugham as a novelist.  He is considered by some to be trashy, and this complements Mildred’s character in Of Human Bondage. Unusually for a male author can be considered middlebrow. We will look into this more next week when we screen Rain (1932) which is a screen translation of his 1921 short story.

He is considered by some to be trashy, and this complements Mildred’s character in Of Human Bondage. Unusually for a male author can be considered middlebrow. We will look into this more next week when we screen Rain (1932) which is a screen translation of his 1921 short story.

Many thanks to Ann-Marie for choosing such a wonderful film which certainly gave us plenty to chew over…

As ever, do log in to comment, or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk to add your thoughts.