Posted by Sarah,

Frances has very kindly provided the following summary of our post-screening discussion on The Skin I Live In (2011):

This week’s discussion centred on the topics of sexual identity, motherhood and other representations of femininity, performance and the use of the male gaze as evoked by the screening of The Skin I Live In. The session began with an introduction from Keeley, as well as some notes on the film’s production from Rosa. Rosa explained how the shooting of the film was quite stressful for all involved and this seems to have affected the performance of the actors in the film which is particularly apt for the film’s troubling themes. A lot of the film was shot at night and on location and Almódovar was quite an excessive character to work with, demanding sets be re-built from scratch if they did not meet his exacting standards. Rosa also noted how the colour red is important for the film, and Spanish culture more widely, representing as it does passion, love, war, blood, fire and sexuality. Almódovar is particularly adept at  utilising the colour as red can be found in a lot of his films (especially on the posters) and red is also present somewhere in the frame in most of the shots in this film. Rosa also told us that the vintage shop seen in The Skin I Live In is a real shop belonging to costume designer Paco Delgado (who, more recently, has worked on and received an award nomination for Les Miserables).

utilising the colour as red can be found in a lot of his films (especially on the posters) and red is also present somewhere in the frame in most of the shots in this film. Rosa also told us that the vintage shop seen in The Skin I Live In is a real shop belonging to costume designer Paco Delgado (who, more recently, has worked on and received an award nomination for Les Miserables).

Rosa remarked how these anecdotes of a difficult shoot are fascinating to consider, as they both reveal the unique workings of the director and how such a stressful production, combined with a difficult plot, can infect the crew and their modus operandi. Rosa commented that this production history translates into the viewing experience of the film, as The Skin I Live In draws audiences into its complicated tone and difficult story, as though making them a ‘prisoner’ of the film as well.

Keeley offered another thorough introduction to the film which focused on the main themes of the narrative. She mentioned how, in particular, maternal devotion, sexual identity, family relationships and the home are central to the film. Another recurring and important motif is that of the double: this is present on a narrative level with the physical transformation of Vicente to Vera, but it is also apparent elsewhere in the film, such as with the visual similarity of characters (Vera is made to look like Robert’s deceased wife)  and through the comparable roles assigned to characters (there are three mothers which feature in the film). The double can also said to be present in the way The Skin I Live In relates to other melodramas, such as Frankenstein, Eyes Without a Face and Rebecca. Obsession and sexual identity also features in the narratives of these films, just as it does in The Skin I Live In.

and through the comparable roles assigned to characters (there are three mothers which feature in the film). The double can also said to be present in the way The Skin I Live In relates to other melodramas, such as Frankenstein, Eyes Without a Face and Rebecca. Obsession and sexual identity also features in the narratives of these films, just as it does in The Skin I Live In.

Keeley found the following quote particularly helpful in thinking about this film. It reads:

“In its final scenes, The Skin I Live In takes a turn that is as unexpected as it is brilliant. It no longer tells a story or revenge, but rather the story of a conversion.” (Gustavo Martin Garzo in The Pedro Almodovar Archives, edited by Paul Duncan & Bárbara Peiró, 2011. p. 373).

The film, in this way, is about accepting (or not) the identity forced upon you and this has particular implications for the film’s ending: is this positive or not? Keeley stated she thought that it was as it signalled hope for Vera and this was a discussion point we returned to later. Keeley also noted that The Skin I Live In is an important film to think about Almódovar as an auteur and where it fits into his larger body of work. This film is, in many ways, Almódovar’s most polished film although  melodrama runs throughout all of his films. The Skin I Live In is a denser and more emotionally complex film. It is also interesting that Antonio Banderas should appear in the film: this is his first film with Almódovar for a long time and also signals Banderas’ return to Spanish film. The Skin I Live In allowed Banderas to explore a deeply emotional character and our reaction to Robert was another discussion point we returned to later.

melodrama runs throughout all of his films. The Skin I Live In is a denser and more emotionally complex film. It is also interesting that Antonio Banderas should appear in the film: this is his first film with Almódovar for a long time and also signals Banderas’ return to Spanish film. The Skin I Live In allowed Banderas to explore a deeply emotional character and our reaction to Robert was another discussion point we returned to later.

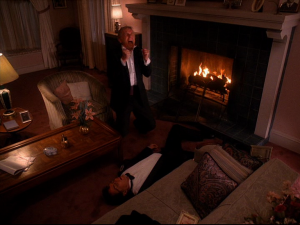

After the screening of the film, comments opened with the thought that secrets are an incredibly important aspect to the film’s narrative and melodrama more widely. The secret as to the ‘true self’ occurred on several occasions in The Skin I Live In and is reflected by the film’s unusual structure: the crucial backstory explaining who Vera is – and how she became Vera – is delayed. Another delay occurs with Vera’s true intentions, which sees her murdering Robert at the end. There is some debate whether this was Vera’s plan all along or as a result of seeing Vicente’s image in the newspaper again after all those years. Vera’s actions at the end of the film are also complicated because the love making scene which takes place between her and Robert seems genuine and affectionate and therefore not does hint at Vera’s murderous intent moments later.

The relationship between Vera and Robert was discussed at length and we commented how the almost incestuous nature of their coupling is an important part of the film’s difficult narrative (by making love to Vera, Robert is having sex with the person who raped his daughter). We agreed that the most disturbing sex scene is the earlier one between Robert and Vera, following the latter’s rape by Zeca the ‘tiger man’. Although Robert clearly expresses his desire for Vera earlier on in the film (by watching her intently on the large TV screen), this sexual liaison  appears to be for the purpose of Robert reclaiming Vera as his ‘property’ and ‘marking his territory’ after her defilement by the tiger man. The fact all of these scenes take place before the revelation of Vera’s original identity and early on in the narrative, makes the film an uncomfortable viewing experience from the start.

appears to be for the purpose of Robert reclaiming Vera as his ‘property’ and ‘marking his territory’ after her defilement by the tiger man. The fact all of these scenes take place before the revelation of Vera’s original identity and early on in the narrative, makes the film an uncomfortable viewing experience from the start.

We discussed the film’s enigmatic ending and Keeley explained how she finds this conclusion quite hopeful for Vera: Vera’s return to the shop points to the cyclical nature of the narrative and emphasises how she is now free from her captivity. The shop assistant is important to this scene: we see earlier Vicente’s banter with his fellow employee and the emotional and physical attraction between them is evident again at the end, perhaps even more so with Vicente’s transformation into Vera. The shop also seems like a fitting and safe place for Vera to return to not only because this is home but because this is the only place where we see some humour in the film take place (the dubious customer service and buying of ‘fat’ clothes seen earlier in the film when we are first introduced to Vicente). Yet even in this seemingly light-hearted sequence, the film appears to prophesise Vicente’s demise, as there is a visual match between the  early shot of the dress in the window (with Vicente on the inside of the shop), and the shot of the dress in the window again at the end (with Vera reflected from the outside). Keeley also noted how this latter shot features a background patterning in the shop which is similar to the drawings Vera makes on the walls of her locked room in Robert’s house, as though foreshadowing Vicente’s inevitable imprisonment as Vera.

early shot of the dress in the window (with Vicente on the inside of the shop), and the shot of the dress in the window again at the end (with Vera reflected from the outside). Keeley also noted how this latter shot features a background patterning in the shop which is similar to the drawings Vera makes on the walls of her locked room in Robert’s house, as though foreshadowing Vicente’s inevitable imprisonment as Vera.

Although there is a hopeful tone to the film’s concluding moments, the ending is not without its ambiguities and frustrations for the viewer either. Importantly, the film fades to black before Vicente’s mother can react to her son’s new appearance, which is also significant because the mother firmly told the police that she believed her son to still be alive. We expanded this point to comment how an integral part of the melodrama of the film is not just the suffering of Robert and Vera (and, by extension, Norma whose downfall is a combination of her mother’s death and Vicente’s actions), but the narrative also includes three suffering mothers. These are: Robert’s mother, who tells Vera her tragic life story and is also the mother of Zeca; Robert’s wife, who attempts to elope with Zeca but is left to burn in their crashed car and eventually commits suicide; and Vicente’s mother, whose child is pronounced dead by the authorities even though she believes he was kidnapped. Therefore The Skin I Live In features several personal melodramas occurring simultaneously and the complexity with which these stories relate poses a challenge for spectators and their engagement with these characters.

commits suicide; and Vicente’s mother, whose child is pronounced dead by the authorities even though she believes he was kidnapped. Therefore The Skin I Live In features several personal melodramas occurring simultaneously and the complexity with which these stories relate poses a challenge for spectators and their engagement with these characters.

We also discussed how performance, identity, and costume become conflated in The Skin I Live In, with characters frequently embodying the roles of their outer appearance. For example, Zeca’s tiger ‘skin’ is an apt costume as he acts aggressively first towards his mother (who he ties up in the kitchen) and then towards Vera. Zeca’s depraved treatment of Vera begins by him licking the TV screen displaying Vera in her locked room and we then see several cuts of Zeca ‘stalking’ his prey before raping her. Vera also plays the role dictated to by her outward appearance. For example we see Vera perform domestic chores, cleaning her room and preparing breakfast for Robert. Robert  attempts to enforce a very specific definition of femininity onto Vera, by supplying her with dresses and make up. Yet Vera also uses her new ‘feminine wiles’ to trick Robert, as when she attacks him when wearing the black stocking she asked him to zip up, or later when Vera tries to convince Robert to give her freedom to roam the house by attempting to seduce him.

attempts to enforce a very specific definition of femininity onto Vera, by supplying her with dresses and make up. Yet Vera also uses her new ‘feminine wiles’ to trick Robert, as when she attacks him when wearing the black stocking she asked him to zip up, or later when Vera tries to convince Robert to give her freedom to roam the house by attempting to seduce him.

This rather stereotypical representation of the feminine is also emphasised by the exaggerated use of the male gaze in the film. This occurs with Zeca and his licking of the TV screen, but Vera is also subjected to Robert’s gaze. Robert watches Vera on the huge TV screen in his room and he fragments Vera’s body for his own gratification by zooming the camera in on Vera and again, quite literally, through the process he performs to transform Vicente into Vera and the other procedures he performs to reinforce her skin. Vera’s body is also juxtaposed with the paintings of figures in Robert’s house and the clay bodies Vera makes and decorates with her torn dresses. Yet Vera also subverts this male gaze by performing for it: she knows Robert watches her and Vera hopes this knowledge of Robert’s attraction towards her will help win her freedom. Vera also returns the gaze: she looks down the camera towards Robert forcing him to reflect upon his own act of looking. The male gaze is subverted again as it is Robert’s and Zeca’s mother who witnesses Vera’s rape on the TV screens.

is also emphasised by the exaggerated use of the male gaze in the film. This occurs with Zeca and his licking of the TV screen, but Vera is also subjected to Robert’s gaze. Robert watches Vera on the huge TV screen in his room and he fragments Vera’s body for his own gratification by zooming the camera in on Vera and again, quite literally, through the process he performs to transform Vicente into Vera and the other procedures he performs to reinforce her skin. Vera’s body is also juxtaposed with the paintings of figures in Robert’s house and the clay bodies Vera makes and decorates with her torn dresses. Yet Vera also subverts this male gaze by performing for it: she knows Robert watches her and Vera hopes this knowledge of Robert’s attraction towards her will help win her freedom. Vera also returns the gaze: she looks down the camera towards Robert forcing him to reflect upon his own act of looking. The male gaze is subverted again as it is Robert’s and Zeca’s mother who witnesses Vera’s rape on the TV screens.

We commented on the unusual structure of the house, where the majority of the film’s melodramatic moments takes place. The house’s geography is complicated and it remains unclear where the distinctive areas of the house exist in relation to each other (thus contributing to Vera’s hopelessness at achieving freedom on one occasion). There is also a strange mix of styles present in the home, with the cave-like place where Vicente is kept initially, combining with the traditional façade of the house (and rooms like the kitchen), which in turn contrast sharply with the clinical sight of the operating theatre. The film’s central debate of whether one is ‘at home’ in one’s own skin and ultimately defined by this outwardly appearance is thus mirrored by the house’s abnormal structure: it, too, is an ‘un-homely’ home.

We also discussed how the central event in the narrative – Norma’s rape – does not evoke the ‘melodramatic showdown’ one might expect from such a story. Indeed this part of the story is the most difficult to interpret, as Vicente expresses to Robert that “I don’t think I raped her [Norma]”. The scene depicting Vicente’s encounter with Norma is challenging: at first Norma seems to be engaged with Vicente’s attraction to her but, after the edit which takes us back into the house and to the wedding party, her participation in the liaison is no longer consensual. The scene is also difficult to evaluate because it is clearly portrayed as a subjective memory, as both Vera and Robert’s dreams take us into these flashbacks.

We also discussed how the central event in the narrative – Norma’s rape – does not evoke the ‘melodramatic showdown’ one might expect from such a story. Indeed this part of the story is the most difficult to interpret, as Vicente expresses to Robert that “I don’t think I raped her [Norma]”. The scene depicting Vicente’s encounter with Norma is challenging: at first Norma seems to be engaged with Vicente’s attraction to her but, after the edit which takes us back into the house and to the wedding party, her participation in the liaison is no longer consensual. The scene is also difficult to evaluate because it is clearly portrayed as a subjective memory, as both Vera and Robert’s dreams take us into these flashbacks. Leaving aside the question of whether such memories are to be considered reliable, the difficulty for interpretation and identification is pushed further as Vicente’s original role as the rapist and Robert as the doting and loving father is swiftly usurped by Vera’s depiction as the victim and Robert as the oppressor. The moral compass of the film is constantly misdirected and confused.

Leaving aside the question of whether such memories are to be considered reliable, the difficulty for interpretation and identification is pushed further as Vicente’s original role as the rapist and Robert as the doting and loving father is swiftly usurped by Vera’s depiction as the victim and Robert as the oppressor. The moral compass of the film is constantly misdirected and confused.

We concluded our discussion by talking about how successful and well received the film was on its release. This is in contrast to this week’s set reading from Film Quarterly, which was quite dismissive of the film’s representations of sex, sexuality, aesthetic qualities and apparent misogyny. We disagreed with these conclusions as we found the challenges posed by these questions an important part of the viewing experience for a film which does not offer any easy answers.

Many thanks to Kat, Keeley and Frances for jointly selecting such a fascinating film for us to view, and for providing the great introductions and summary. Thanks too to Rosa for the extra, inside, information on Almodovar.

Do, as always log in to comment, or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk to add your thoughts.