If we want to make improvements at work we need to balance between two sets of action: reduction of waste and addition of value. William Sherkenbach reminds us that waste and value are NOT reciprocals

– you can reduce waste but not add value;

– you can add value but not reduce waste.

You need to do both in a balanced way. The reduction of waste does not ensure value.

This is why John Seddon always starts discussions around improvement by asking people to understand what is happening first; how much good work they produce (the stuff that people want) and what it is (why it is valuable), how much waste is produced (stuff that is not what people want) and what types of waste. Seddon calls these the WHAT’s of performance. Only once we know what is happening can we differentiate value from waste (or ‘failure demand’ as Seddon labels it). What is interesting is that by examining demand properly we can identify those things which on the surface appear to be a customer requirement (e.g. a request for a service or a query) but can actually turn out to be driven by a failure earlier in the process. If these things are identified we can flush out built-in failures in the design of systems, procedures and policies.

To some degree or another, a given production of good output (value) will generate a parallel degree of waste. If you double the output (good things), you will double the waste output (at the very least, aside from errors due to additional pressure on people and machinery). To improve quality of output (i.e. to get proportionally more good stuff) we need to redesign the system. Identify value and eliminate waste and failure.

An analogy is water consumption. If you find a new source of water and make it available for consumers to use, but don’t fix the leaky pipes, you will just generate more leaked water. A good water system has good supply of water and a continually diminishing occurrence of leaks. Water service professionals are concerned with water catchment (source and supply channels) and the integrity of the distribution network (fixing leaks).

However, taking the idea further using a different analogy, an economical way to run a car involves a combination of maintenance and driving technique for improved fuel efficiency, or a person could simply drive the vehicle fewer miles. How you carry out your driving relates to purpose. If we only drive a few blocks to buy a pint of milk, our decision about the car’s fuel economy might be different compared to someone who uses the car to commute 100 miles per day to work. Or, if we only want to take our prized sports coupé out at weekends in the summer to impress people at parties, the decision will be different once again.

Purpose is defined by the needs of the user. The ‘user’ is the user of our product or service. But also remember that ‘purpose’ should not exist in its own bubble. If we buy a Harley Davidson motorcycle just to use it to cruise in the sunshine on Sundays, that might be just fine. However, if we ‘rev it up’ every Sunday morning as we start our trip to the seaside, the neighbours might have something to say about it.

Purpose, value & waste. The start for discussions about performance is to understand all three.

Further Reading:

Seddon, J. (2005) Freedom from Command and Control, Vanguard Press, Buckingham, UK.

Sherkenbach W.W. (1991) Deming’s Road to Continuous Improvement, SPC Press, Knoxville, TE

The idea of ‘culture change’ has been around at least since the 1970s.

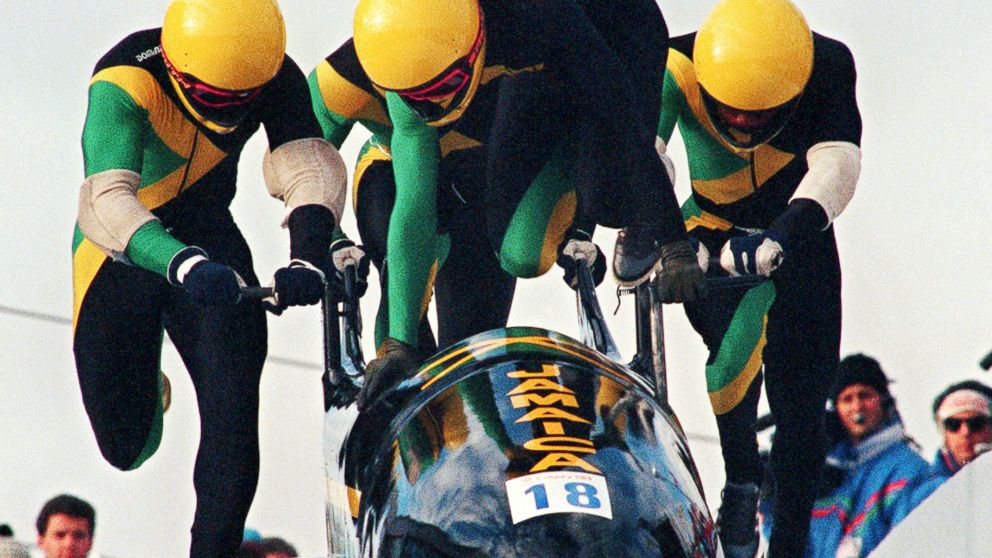

The idea of ‘culture change’ has been around at least since the 1970s. It is a sporting theme again, inspired by the thrills of the Winter Olympics. Let’s hark back to the 1988 Calgary Games, memorable since British involvement started to impress outside the ice-rink. Eccentricities of Eddie ‘the Eagle’ Edwards, our first Olympic ski-jumper matched Martin Bell’s efforts in the men’s downhill. Even our bob-sledders were competitive.

It is a sporting theme again, inspired by the thrills of the Winter Olympics. Let’s hark back to the 1988 Calgary Games, memorable since British involvement started to impress outside the ice-rink. Eccentricities of Eddie ‘the Eagle’ Edwards, our first Olympic ski-jumper matched Martin Bell’s efforts in the men’s downhill. Even our bob-sledders were competitive. ‘Partnerships’ might become the new buzzword of the year. But what is this

‘Partnerships’ might become the new buzzword of the year. But what is this