While volunteering at the University of Kent’s special collections, I was cataloguing the C. P. Davies Collection of Mill Memorabilia and the collection threw up many surprises. One, which I was not prepared for was how some of the documents were earlier versions of things that we often think of as exclusively modern. By modern I mean post-war. However, it was genuinely surprising to see a personalised pencil from the late 19th century, recorded post, a picture from a sport’s work day, letters about everyday life as a tenant and the fascination with family history. These things, I believed, were quite modern creations (especially the personalized pencil) but by finding them in this 19th/ early 20th century collection, it made think how different are we really to people of just over 100 years ago? How different are our priorities, our cares, our worries? Obviously, we are so unlike in many ways: technology, general attitudes, work, shopping… There are so many developments to name! However, sometimes, we get a glimpse into how similar we are to past generations. A chance to take people from the past and make them more than just a memory, but empathise and understand their world that little bit more. It is this idea that makes me love history. I have called this piece after a lyric in Les Misérables as I thought that not only does it show the closeness between ourselves and a past generation, but also I hope that people in the future will be able to look back at us and seem the similarities of our everyday life to theirs.

- Dover Mills, Box 1, Item 75

The first and perhaps one of my favourite items in the collection is this personalised pencil of the owner of Buckland Mill, Edward Mannering. I remember having personalised pencils (both drawing and colouring) when I was younger and I suppose that I had always thought of these as an invention on the post war era. But to find one which could be traced to the late 19th early 20th century was a pleasant surprise. I loved the little flourished design either sides of his name. Moreover, you can see where the owner has sharpened the pencil with a knife. Perhaps the owner stopped in order to preserve the name and thus shows us the care people could have for their belongings, just as we have today.

- Dover Mills, Box 1, Item 21

This next photo I found fascinating because it gave a face to the ordinary men that worked in the Mannering Mill’s in 1908. A chance to see the faces of those from less well-off backgrounds in history is rare until the development and spread of the camera. This looks like a type of sports day as you can see that the spectators in the backgrounds have a rope to separate them from what could be the track. These men, stood all in flour sacks could have been taking part in a sack race. There is no hint as to whether these men worked in the mill but it could be a safe conclusion to draw. It is also unclear as to whether the mill owners would have organised this type of sports day or whether it was a general community day for all those close to the Dover mills. But again like the pencil, I had long thought that this idea of a community/work sports day was a modern invention, like dress down Fridays. However, this picture sparks many questions and ideas as to how Edwardian communities would come together, what they would do and why? It is a nostalgic ideal of a community all coming together and one of the few things in this blog that I found has unfortunately depleted throughout the years.

The recent upsurge in the interest in family history has been shown with the many adverts for genealogy history by sites like Ancestory.com. The idea of researching and presenting you past is not new (Noblemen of the Middle Ages would have wanted to show off their illustrious family tree). But some historians have criticised the idea of ordinary people collecting their family history as not really helpful for the bigger study of history – but some highlight the chance for new angles of research[1]. However, by having this research done on the Pilcher family, we have a lot of background information as to who owned various mills in Kent and their life story. Niche areas of history are becoming ever more popular and it is this type of research that is invaluable to people interested in the topic. Moreover, the ability to trace a family from 1598 to 1952 can help in so many other regions of history. So I included this document because of its vast usefulness as a source but also to show the enduring appeal of genealogy and the continuing importance, despite some historians protests, of its use to general history.

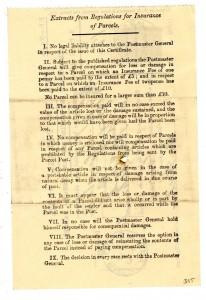

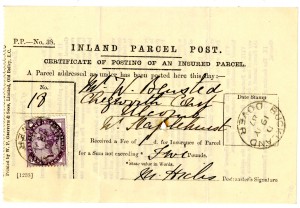

The postal service has been an important part of the country for many generations and although we all have our modern gripes with the system,we still rely on it regularly to transport our letters and parcels. But for special items, we would usually get a recorded delivery so as to ensure the safe deliverance of the item. Like many, I presumed that it was only in recent years, as the country expanded and long distant relationships became more normal, did the invention of recorded post come about. But my opinion was soon changed when I perceived this ‘certificate of posting of an insured parcel’ with in the C. P. Davies Collection. I loved seeing all of the terms and conditions on the back of the note explain who was responsible for what and what would be done in case of loss or damage (and to be honest, the terms and conditions are a step that we all skip over from time to time). However, unlike today’s jargon-busting maze of terms, the sheer simplicity and openness of the regulations was something that I wish had continued from this period!

What this small slip of paper also reveals to us is that people must have cared about what they were sending and, similar to the pencil, the attachment we see to object is much like our own. Moreover, the want to ensure that something personal or important has arrived at its destination is the exact same mind-set that we have today, whether it be a birthday cheque or a return for student finance! Thus, I included this small note because of the charm I found in the regulations but furthermore, because I could identify why we would want certain things we post to be protected.

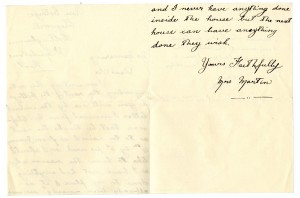

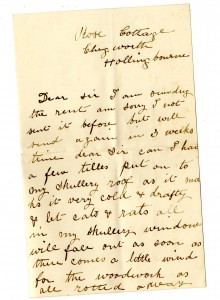

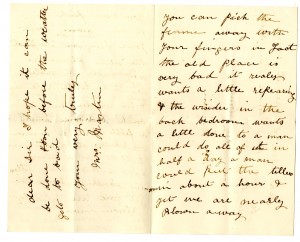

The next item I chose was because of its simple ability of letting us see someone’s everyday life from the earl part of the 20th century. The letters from Mrs Martin to her landlord, Mr Mannering, were among my favourite documents in the collection and reading them always put a smile on my face. From her letter, I could really paint a picture in my mind’s eye of this lady and what she was like (all from the expression of her words, the tone, and the phrases that she uses in the letters). The first picture is the end part of a letter in which she questions the rise in her rent (although in other letters, despite her protests, she does seem to have shortcoming with regards to the rent). What I found interesting was the final sentence of: “I never have anything done inside my house but the next house can have anything done they wish”. To me, not only is there a bitter jealous tone, but I sense

that there is a massive hint that she would like improvements done to her house, but she does not wish to out rightly say. I could empathise with this as I started to think that we all, at some point, out of politeness try to ask or hint at things that we would like in an indirect way. The next letter I picked out follows this trend of wishing for work to be done, but has less of the jealous tone, more of the ‘woe-is-me’ feel about the letter. She starts off asking for some new tiles on the roof as it is “cold and drafty” but this then snowballs into the idea that it lets “cats and rats” into her scullery. Furthermore, it has resulted in the rotting away of the woodwork of her window as ”you can pick the frame away with your fingers” (which to me suggests that she has been occupied with this problem for some time). Finally she concludes by saying that “the old place is very bad it really wants a little repairing”. The endless list of issues with the house that all seem to stem from one another gives a sense of hyperbole which made me smile while reading it. The problems she had can be so easily transferable onto our modern world, that we can really see the startling similarities to our modern reliance on councils or landlords to help fix and maintain our houses.

In conclusion, I hope you have enjoyed looking at some of the unique and interesting items that I found within the C. P. Davies Collection and that, just as they have done for me, they have shown you how many similarities we still have with the past (despite the general consensus that we have changed and that we are so different from our ancestors 100 years ago). These little items can reveal to us so much about everyday life, a topic which is only just being revealed to us in the past few decades. Some may not see a past generation’s everyday life as particularly exciting or interesting compared with big events like the Reformation or World War One; however these are big events that radically changed society (hence why we all have this perception of drastic change). It was nice to discover these artefacts and documents and see that, below the surface, the themes and attitudes to everyday life such as community, care of belongings, up keep of a house etc. can be seen as relatively the same as over a century ago. Of course there are some small differences between us (a shown in some of these documents) however, as the title suggests, our basic cares and worries in the world, regardless of the mass changes that happen, seem to always continue on a steady course.

By Charlotte Daynton

Please comment below with your thoughts on the items featured or if you have any more information about the materials covered.

[1] Tim Brennan, ‘History, Family, History.’, in Hilda Kean, Paul Martin and Sally J.Morgan (eds.), Seeing History: Public History in Britain Now, (London: Francis Boutle Publishers, 2000), p.44.