After recovering from the experience of watching all the dramatic happenings, our discussion of the film included: the second Mrs de Winter as ‘gothic heroine’ in terms of her being an ‘almost investigator’ as well as her naivety and youth; the way ‘dress tells the woman’s story’; Mrs Danvers’ literal and metaphorical hand in running the house; Hitchcockian set-pieces; the eternal mystery of Rebecca.

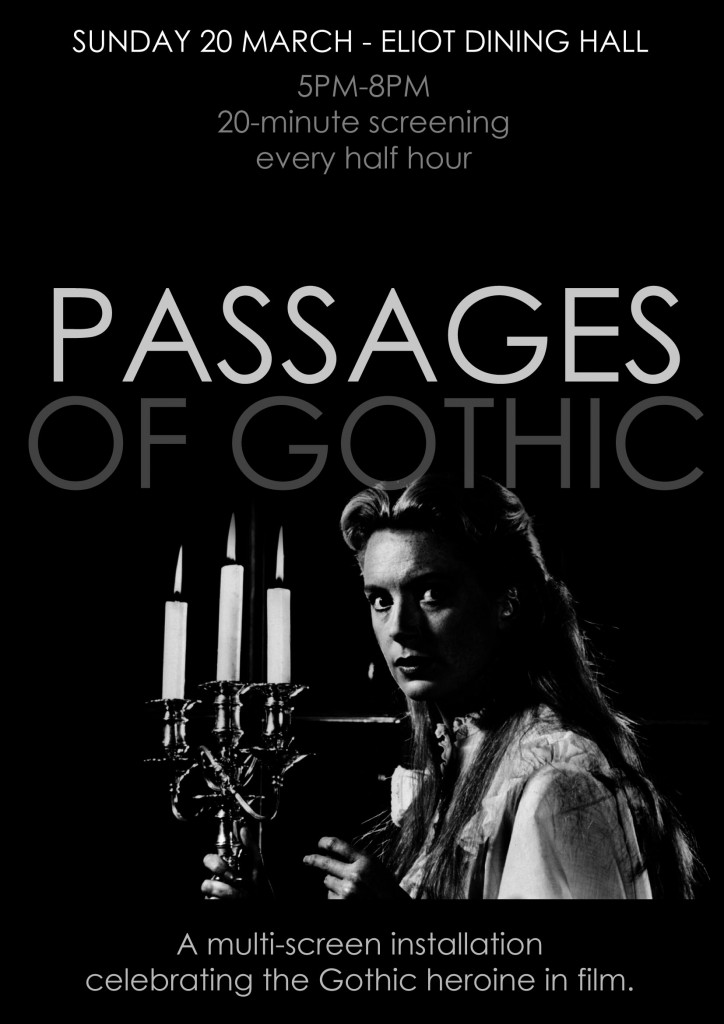

We began by noting some differences between the second Mrs de Winter (Joan Fontaine) and other Gothic film heroines. Comparison to Mrs Danvers (Judith Anderson) elucidates this matter. Some of our recent focus has been on Gothic heroine as explorer – often in the dark, with a candlestick, and that this, in opposition to some expectations, reveals the woman actively exploring space. In Rebecca only Mrs Danvers receives this attention. This occurs toward the film’s end, just prior to her setting light to Manderley. We are afforded a shot of Danvers, with the candle light playing wickedly on her face, and it is soon revealed she is creeping towards a sleeping, innocent and endangered second Mrs de Winter.

expectations, reveals the woman actively exploring space. In Rebecca only Mrs Danvers receives this attention. This occurs toward the film’s end, just prior to her setting light to Manderley. We are afforded a shot of Danvers, with the candle light playing wickedly on her face, and it is soon revealed she is creeping towards a sleeping, innocent and endangered second Mrs de Winter.

The second Mrs de Winter does, nonetheless, get to explore the space of the house to an extent. She is what Lisa M. Dresner terms as ‘almost investigator’ (pp. 163-4)[i]. Indeed most of the second Mrs de Winter’s movement around the house is somewhat blundering. Understandably she is unfamiliar with where certain rooms are situated. Notably she also manages to trip over her own feet, rather like a puppy, in front of the servants as she exits the dining room following her first hurried breakfast.

The second Mrs de Winter does, nonetheless, get to explore the space of the house to an extent. She is what Lisa M. Dresner terms as ‘almost investigator’ (pp. 163-4)[i]. Indeed most of the second Mrs de Winter’s movement around the house is somewhat blundering. Understandably she is unfamiliar with where certain rooms are situated. Notably she also manages to trip over her own feet, rather like a puppy, in front of the servants as she exits the dining room following her first hurried breakfast.

Such clumsiness links to the character’s youth. Her naivety and innocence prized by Maxim (Laurence Oliver) who states that he wants her to say a ‘child’ and a ‘girl’. The film is a ‘growing-up’ narrative, however, with the second Mrs de Winter gaining confidence as time progresses. This is especially shown by costume. The pale twinset and tweed skirt and unadorned or Alice-banded hair which characterise her early in the film gives way to her wearing a sophisticated black evening gown and pearls. Her excitement at her new dress is soon quelled by Maxim. After his unenthusiastic reaction – he reminds her that he stated at the beginning of their romance that he never wanted to see her wearing a black gown and a string of pearls – she looks uncomfortable, tugging at her dress. Maxim is made even angrier when his new wife dons a copy of Lady Caroline de Winter’s dress. She finds her level in the dark tailored skirt suit and hat she wears at the inquest into Rebecca’s death.

Such clumsiness links to the character’s youth. Her naivety and innocence prized by Maxim (Laurence Oliver) who states that he wants her to say a ‘child’ and a ‘girl’. The film is a ‘growing-up’ narrative, however, with the second Mrs de Winter gaining confidence as time progresses. This is especially shown by costume. The pale twinset and tweed skirt and unadorned or Alice-banded hair which characterise her early in the film gives way to her wearing a sophisticated black evening gown and pearls. Her excitement at her new dress is soon quelled by Maxim. After his unenthusiastic reaction – he reminds her that he stated at the beginning of their romance that he never wanted to see her wearing a black gown and a string of pearls – she looks uncomfortable, tugging at her dress. Maxim is made even angrier when his new wife dons a copy of Lady Caroline de Winter’s dress. She finds her level in the dark tailored skirt suit and hat she wears at the inquest into Rebecca’s death.  This comments on, as Jane Gaines expresses, ‘how dress tells the woman’s story’[ii]. We also commented that Maxim comes to appreciate his second wife’s newly-found strength, with the film also focusing on how he comes to terms with her evolution.

This comments on, as Jane Gaines expresses, ‘how dress tells the woman’s story’[ii]. We also commented that Maxim comes to appreciate his second wife’s newly-found strength, with the film also focusing on how he comes to terms with her evolution.

Rebecca’s costumes also play an important part in the film. In addition to the second Mrs de Winter unwittingly copying the last dress her predecessor wore at a ball, Mrs Danvers’s treatment of Rebecca’s clothes is revealing. She has kept Rebecca’s bedroom just as it was and insists on showing it to her previous mistress’ replacement. Danvers’ handling of Rebecca’s fur coat and especially her sheer underwear are significant – she tellingly states that ‘you can see my hand’ thought the flimsy fabric of the negligee.

Danvers’s treatment of Rebecca’s clothes is revealing. She has kept Rebecca’s bedroom just as it was and insists on showing it to her previous mistress’ replacement. Danvers’ handling of Rebecca’s fur coat and especially her sheer underwear are significant – she tellingly states that ‘you can see my hand’ thought the flimsy fabric of the negligee.

This literal hand also directs our attention to Danvers’ more metaphorical hand in directing the second Mrs de Winter around the space of Rebecca’s bedroom, motioning to her to sit whilst she pretends to brush the substitute Rebecca’s hair. Danvers’ control extends to the rest of the house. She has also kept the morning room just as it was – complete with Rebecca’s address book, menus, and compromising letters. Danvers’ domination of the house, and arguably the film, is seen in the even more public space of the entrance hall. This is especially evident when we compare the second Mrs de Winter’s return to Manderley (at the opening of the film) to her initial entrance. In the former she is in charge of the voice over narration, framing our understanding, while in the latter. Danvers has stamped her authority by lining up her battalion of staff to intimidate her new mistress. The blurring between the drawing of battle lines between the two women and the possibility of the second Mrs de Winter replacing Rebecca in  Danvers’ affections is shown in one simple but effective gesture in this scene. It is revealed that the second Mrs de Winter has dropped her gloves and both women bend to retrieve them. While this shows the second Mrs de Winter’s unease around servants it might also be interpreted as either her unwittingly throwing down the gauntlet to Danvers or indeed as a courtship ritual.

Danvers’ affections is shown in one simple but effective gesture in this scene. It is revealed that the second Mrs de Winter has dropped her gloves and both women bend to retrieve them. While this shows the second Mrs de Winter’s unease around servants it might also be interpreted as either her unwittingly throwing down the gauntlet to Danvers or indeed as a courtship ritual.

Judith Anderson’s intriguing and creepily effective performance also prompted thought about the way her part was written compared to the final film product. Furthermore we noted some Hitchcockian set-pieces. The audience’s watching of the newly-wedded couple screening their honeymoon home movies masterfully contrasts the carefree happenings on screen to the now stilted relationship of the pair. This occurs just after Maxim’s unenthusiastic response to his wife’s new dress and he starts to behave in an even more threatening manner, at times moving in front of the projector and blocking his wife (and our) access to the home movies. (See Mary Ann Doane for a great analysis of this scene – pp. 163-169.)[iii]

couple screening their honeymoon home movies masterfully contrasts the carefree happenings on screen to the now stilted relationship of the pair. This occurs just after Maxim’s unenthusiastic response to his wife’s new dress and he starts to behave in an even more threatening manner, at times moving in front of the projector and blocking his wife (and our) access to the home movies. (See Mary Ann Doane for a great analysis of this scene – pp. 163-169.)[iii]

Sound was more dominant elsewhere as close ups of a ringing phone appeared on two notable occasions. In the first, at the Monte Carlo hotel, the soon-to-be second Mrs de Winter leaves her room due to the orders of her employer, the ghastly Mrs Van Hopper, just as Maxim returns her call. The second at the cottage on the beach is more dramatic, interrupting Maxim’s confession to his new wife. The set is especially atmospheric, if perhaps unbelievable with its still connected telephone, stubbed out cigarettes and cobwebs. We also compared Rebecca to some of Hitchcock’s other works. Rear Window (1954) also includes a tense phone call scene though we thought the tone of Rebecca better matched The Lady Vanishes (1939) – partly due to the Britishness (or affected Britishness) of the actors in both.

Sound was more dominant elsewhere as close ups of a ringing phone appeared on two notable occasions. In the first, at the Monte Carlo hotel, the soon-to-be second Mrs de Winter leaves her room due to the orders of her employer, the ghastly Mrs Van Hopper, just as Maxim returns her call. The second at the cottage on the beach is more dramatic, interrupting Maxim’s confession to his new wife. The set is especially atmospheric, if perhaps unbelievable with its still connected telephone, stubbed out cigarettes and cobwebs. We also compared Rebecca to some of Hitchcock’s other works. Rear Window (1954) also includes a tense phone call scene though we thought the tone of Rebecca better matched The Lady Vanishes (1939) – partly due to the Britishness (or affected Britishness) of the actors in both.

We ended by commenting that in the end we knew little about either Mrs de Winter. Speculation about Rebecca’s ‘unspeakable’ behaviour dominated. Despite the Hays Code, the film is explicit that Rebecca has been indulging in an adulterous affair with her cousin Favell (George Sanders) which may have resulted in a pregnancy. But what previous medical ailments meant she needed to visit the backstreet doctor several times under the alias of Mrs Danvers? And what was the nature of the relation between Rebecca and ‘Danny’? Tamar mentioned that at around the time of writing Rebecca Daphne Du Maurier wrote a short story also focused on a character named Rebecca. This Rebecca’s aberrant behaviour is elucidated – she behaves coldly to the story’s male narrator as she finds her sexual fulfilment with a wooden doll.

Apologies for the spoiler, but you can find the story in full here: http://www.theguardian.com/books/2011/apr/30/the-doll-daphne-du-maurier

In addition, here are some posts about Rebecca on The Toast’s website Lies mentioned:

http://the-toast.net/2015/07/13/the-sequel-to-rebecca-the-second-mrs-de-winter-deserves/

http://the-toast.net/2015/10/08/in-1937-daphne-du-maurier-wrote-a-horror-story-about-sex-toys/

[i] Lisa M. Dresner, “A Case Study of Rebecca”. The Female Investigator in Literature, Film, and Popular Culture (2006): 154-182.

[ii] Gaines, Jane. 1991. “Costume and Narrative: How dress tells the woman’s story” in Gaines, Jane and Herzog, Charlotte, eds, Fabrications: Costume and the Female Body. New York and London: Routledge.

[iii] Mary Anne Doane, “Female Spectatorship and the Machines of Projection: Caught and Rebecca.” The Desire to Desire: The Woman’s Film of the 1940s (1987): 155-175.

Do log in to comment or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk to add your thoughts.