Monthly Archives: October 2013

Invitation to join the Melodrama Research Consortium

Posted by Sarah

The Group has received a very kind invitation from Matt Buckley of Rutgers University to join the Melodrama Research Consortium. This sounds like a great way to forge links globally, map the field of melodrama academics and pool melodrama resources. This is a very exciting and worthwhile opportunity so do click through and add your areas of interest.

Matt’s message:

Dear Colleague,

I am writing to invite you to participate in the Melodrama Research Consortium, an international, interdisciplinary project intended to facilitate and advance scholarly research on the topic. The initial aims of the project are twofold: first, to establish an ongoing forum for the exchange of ideas among the many scholars working on melodrama in different periods, contexts, and mediums; and, second, to begin work on a collaborative, open-platform database of the production history of stage, film, and television melodrama.

The need for a forum for the exchange of ideas on the topic is now pressing: both historical and theoretical research is advancing rapidly on many fronts, yet most of us remain largely unaware of often complementary work in different areas. In order to offset this problem, we intend to publish on line an open list of melodrama scholars, including areas of specialization, relevant publications, and contact information, and—if it seems useful—to set up a listserve on the topic.

The need for a database of melodrama’s production history is equally apparent: the now substantial number of scholars working on the topic have begun to recover large portions of melodrama’s complex and extended genealogy, yet these remain largely isolated and scattered among the literature of specialized fields. At the outset, our goal for the database is no more complex than to gain a rough common map of melodrama’s multi-modal, multi-contextual history—to start to bring together, in one place, the many different strands of its development. At a moment when melodrama’s vast and disparate genealogies are exploding into view, and as we struggle with the growing recognition that melodrama’s larger history has unfolded in complex ways across contexts, and not merely in them, the immediate value of such a mapping is obvious.

The larger, more long-term goal of the database is to construct a useful research platform for the kind of broadly comparative and data-intensive scholarship that melodrama, as a mass-produced form of global modernity, seems increasingly to invite and may well soon require. More than other, older forms of aesthetic production, melodrama invites quantitative analysis, both to establish the broad patterns of its formal and medial development and to gain an accurate picture of its longer history of production, distribution, and consumption as a cultural commodity. As some of you already know, I have begun over the past few years to construct a more limited database of early British stage melodrama in order to facilitate my own current work on melodrama’s origins and to establish the foundation for the project. After two years of work by a small handful of part-time research assistants, we now have a searchable digital record of about 1500 plays, including melodramas as well as other closely-related theatrical genres, written and/or produced in Britain between 1800 and 1840. The research value of even that very limited portion of the project has been exceptional: for the first time, it is possible to trace with something more than anecdotal accuracy melodrama’s rising success on the British stage, the manner in which its production expanded and spread across different theatres and populations, and the precise periods and contexts in which its development was punctuated by formal and generic shifts. Expanding that record to include even a schematic database of melodrama’s larger history constitutes a significantly more substantial challenge, but one that will by no means be hard to achieve with even modestly expanded resources.

I’m writing you now because we would like to begin to formalize the project as a consortium in order to start applying this year for the funding support that such an effort will require. You need not play any active role at this point, or perhaps ever. However, I’m hopeful that you might consent to join in a nominal way now so that we might prepare and submit proposals for large, foundational grants as a sizeable international group–and thus gain both greater authority and wider funding eligibility.

Joining the consortium will also, I hope, provide a timely opportunity for those of you whose institutions and disciplines offer funding for collaborative and international projects. As the nature of the database suggests, this project will be a de-centered effort by specialists all over the world and spread across a wide range of fields. With that in mind, please feel free to think of ways in which you might use the project as the basis for more specific proposals to gain internal and area-specific research support. I now have one assistant working exclusively on grant funding, and I would be more than happy to provide whatever support we can for such efforts.

I would be delighted, of course, if any of you would like to take an active or an advisory role. I would be very thankful, too, for any thoughts you might have about the consortium, the database project, or likely sources of support for either, as I am neither a digital savant nor a savvy grant writer. If you would prefer not to join the consortium at this time, I would be grateful if you might consider at least to be included on our listing of melodrama scholars. Even if you are no longer active in the field, it will be helpful for others to know of your work.

You can indicate your reply, provide information about yourself, and join the consortium if you wish, on a google form that we have posted at https://docs.google.com/forms/d/10jphGiR1TN_vpKZfk75JAlEEu7j4UbwPNVvohY6LkSo/viewform. Completing it should take only a few minutes. If you are interested, I would be very grateful if you might respond by November 15, as we intend at that time to generate and post a list of participants in the consortium and scholars in the field.

Please do share this invitation with colleagues and students—the group is intended to be as inclusive as possible, and I certainly don’t know everyone.

With best wishes,

Matt

-- Matthew Buckley Associate Professor Department of English Rutgers University 510 George Street New Brunswick, NJ 08901 646-245-6918

For more info on Matt visit http://english.rutgers.edu/faculty/facultyprofiles/261-mbuckley.html

Do, as ever, log in to comment or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk to add your own thoughts. We could maybe get some discussion going about formalising our specific (individual and group) interests in melodrama.

Melodrama Screening and Discussion, 30th of October, Keynes Seminar Room 6, 4-7 pm

Posted by Sarah

All are welcome to attend the third of this term’s screening and discussion sessions which will take place on the 30th of October in Keynes Seminar Room 6, from 4pm to 7pm.

We will be screening What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962, Robert Aldrich, 124 mins)

Introduction

What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? was adapted from Henry Farrell’s 1960 novel of the same name. The story takes place in a once-fashionable part of Hollywood where two sisters share a dilapidated gothic mansion. ‘Baby’ Jane Hudson was a child star in cinema’s very early days, while Blanche’s heyday was as a movie queen during the 1930s. The sisters are now forced to live together, partly due to a serious accident which has left Blanche wheelchair-bound, and their unhealthy and violent relationship forms the core of the film.

The casting of two of 1930s Holly wood’s greatest female stars – Bette Davis and Joan Crawford – in the roles of the Hudson sisters provoked comment at the time. For example, both the film’s trailer and Variety’s review find the teaming of the stars significant. The trailer touches on the matter of star image as it warns the potential audience that What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? does not resemble the pair’s previous (separate) films. Meanwhile, Variety opines that the casting of Davis and Crawford in retrospect seems like a ‘veritable prerequisite to putting Henry Farrell’s slight tale of terror on the screen’. It certainly led to great returns at the box office: the relatively low budget (just over $1 million) film grossed $9 million.[1]

wood’s greatest female stars – Bette Davis and Joan Crawford – in the roles of the Hudson sisters provoked comment at the time. For example, both the film’s trailer and Variety’s review find the teaming of the stars significant. The trailer touches on the matter of star image as it warns the potential audience that What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? does not resemble the pair’s previous (separate) films. Meanwhile, Variety opines that the casting of Davis and Crawford in retrospect seems like a ‘veritable prerequisite to putting Henry Farrell’s slight tale of terror on the screen’. It certainly led to great returns at the box office: the relatively low budget (just over $1 million) film grossed $9 million.[1]

The film’s production has earned its place in Hollywood folklore in the intervening years. This is primarily due to the assertion that this marked the culmination of Davis and Crawford’s long-running, and some might say melodramatic, feud. Like many Hollywood stories though, this is only partially true. Several sources note the one-upmanship that took place during filming. For example, Bob Thomas’ biography of Crawford details some of the ‘conflict’ between the stars (pp. 224-229). Charlotte Chandler’s ‘personal’ biography of Crawford concludes that the ‘legendary feud between the two may have been just that – a legend’ dreamed up by Baby Jane’s publicity people which the stars both ended up believing (p. 248). Whenever the feud started, and for whatever reason, Davis had very definite ideas about a sequel to the film: “I’ll tell you the first scene. It’ll be a scene of this one,’ pointing at herself, ‘putting flowers on that one’s grave” (p. 250). (A follow-up film Hush… Hush, Sweet Charlotte, was made in 1964 – but with Olivia de Havilland replacing an ill Crawford part-way through).That until Baby Jane Crawford was not really on Davis’ radar is supported by Davis’ autobiography The Lonely Life, published in 1962, which does not even mention Crawford. Davis rectifies this, with relish, in her 1987 post Baby Jane memoir This ‘n That.

The film’s production has earned its place in Hollywood folklore in the intervening years. This is primarily due to the assertion that this marked the culmination of Davis and Crawford’s long-running, and some might say melodramatic, feud. Like many Hollywood stories though, this is only partially true. Several sources note the one-upmanship that took place during filming. For example, Bob Thomas’ biography of Crawford details some of the ‘conflict’ between the stars (pp. 224-229). Charlotte Chandler’s ‘personal’ biography of Crawford concludes that the ‘legendary feud between the two may have been just that – a legend’ dreamed up by Baby Jane’s publicity people which the stars both ended up believing (p. 248). Whenever the feud started, and for whatever reason, Davis had very definite ideas about a sequel to the film: “I’ll tell you the first scene. It’ll be a scene of this one,’ pointing at herself, ‘putting flowers on that one’s grave” (p. 250). (A follow-up film Hush… Hush, Sweet Charlotte, was made in 1964 – but with Olivia de Havilland replacing an ill Crawford part-way through).That until Baby Jane Crawford was not really on Davis’ radar is supported by Davis’ autobiography The Lonely Life, published in 1962, which does not even mention Crawford. Davis rectifies this, with relish, in her 1987 post Baby Jane memoir This ‘n That. Regardless of any melodramatic off-screen tales surrounding What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? the American Film Institute (AFI) Catalog categorises the film text as melodrama. The AFI defines melodramas as ‘fictional films that revolve around suffering protagonists victimized by situations or events related to social distinctions, family and/or sexuality, emphasizing emotion’. [2]

Regardless of any melodramatic off-screen tales surrounding What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? the American Film Institute (AFI) Catalog categorises the film text as melodrama. The AFI defines melodramas as ‘fictional films that revolve around suffering protagonists victimized by situations or events related to social distinctions, family and/or sexuality, emphasizing emotion’. [2]

My analysis of the AFI Catalog shows that What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? was one of 52 melodramas released in 1962. Interestingly, the 1960s showed an upsurge in the production of American produced melodramas. In the 1950s melodramas accounted for 147 films or 4.77% of all American films produced. In the 1960s this had risen to 529 and 22.60%. This does not quite hit the heights of the 1920s (a staggering 2230 or 33.16%) or the 1930s when 434 melodramas (constituting a fairly low 8.14%) were produced. But it is significantly more than in the 1940s (108 or 2.47%) or the 1950s figured quoted above. It might be especially fruitful for us to ponder why this might be the case. Especially as Douglas Sirk’s 1950s melodramas are so often the focus of academic work on melodrama.

Recent scholarly work on What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? has focused on issues of aging, stardom and disability, matters we might well find it interesting to ponder. The articles/chapters include:

Sally Chivers. “Baby Jane Grew Up: The Dramatic Intersection of Age with Disability.” Canadian Review of American Studies 36.2 (2006): 211-228. (See our additional blog: http://melodramaresearchgroupextra.wordpress.com/ for more details.)

Anne Morey. “Grotesquerie as marker of success in aging female stars.” In the limelight and under the microscope: forms and functions of female celebrity (2011). (See our additional blog: http://melodramaresearchgroupextra.wordpress.com/ for more details.)

Also visit the additional blog for more details of Variety’s review.

Access the (fairly non-spoilery) trailer on archive.org: https://archive.org/details/WhateverHappenedToBabyJane-Trailer

Do join us, if you can, for a classic 1960s melodrama with two superb performances from major 1930s female Hollywood stars.

[1] The budget for the film was $1,025,000 according to Alain Silver and James Ursini, Whatever Happened to Robert Aldrich?, Limelight, 1995 p 256. Box Office Information for What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? IMDb. The $9 million figure relates to worldwide grossed. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

[2] http://afi.chadwyck.com/about/genre.htm

Bibliography and suggested further reading

The American Film Institute (AFI) Catalog: http://www.afi.com/members/catalog/

The Internet Movie Database: www.imdb.com

Inspirations: A Celebration of Pam Cook’s Work in Film Studies

Posted by Sarah

Keeley sent me an email to draw the Group’s attention to an event taking place at the University of Southampton on the 9th of November. It is a celebration of renowned film scholar Pam Cook’s work. The speakers include Claire Hines, Richard Dyer, Sarah Street, Catherine Grant, Michael Williams, and of course Pam Cook.

Pam Cook’s work on stardom is especially relevant to our work of the last couple of weeks. In addition, Catherine Grant (former of the University of Kent, now of the University of Sussex) is contributing a video essay entitled: Mirrors, Melodrama and Pam Cook: A Video Essay.

The all-important link: http://www.southampton.ac.uk/film/news/events/2013/11/09_inspirations.page

It looks like a great opportunity, so many thanks to Keeley for mentioning it.

Variety Ultimate Subscription Now Available for Kent Users

Posted by Sarah

There is some very exciting news about a new resource available for those of us who have a University of Kent login. The Templeman Library now has access to Variety Ultimate. This means that most issues of the American trade journal (from 1905-the present) can now be searched and accessed. This is excellent news for research at Kent generally, and, of course, melodrama.

The link: http://chain.kent.ac.uk/login?url=http://www.varietyultimate.com/

I have had a very quick look in terms of film melodrama and found this very early review by ‘Jolo’ of the film The Big Sister on 15th of September 1916, p 26: http://www.varietyultimate.com.chain.kent.ac.uk/archive/issue/WV-09-15-1916-26

The film was directed by John B O’Brien and starred Mae Murray.’Jolo’ opined that the film ‘is melodrama without any attempt at concealment’. The mention of concealment is interesting in two ways. Firstly it indicates the reviewer’s, and the general, rather negative view of melodrama by suggesting that other melodramas might try to appear to be something else. But also, as we have seen, concealment is often a key theme of melodrama.

There will be many, many more exciting nuggets relating to melodrama, so do take a look. And do also share your findings by emailing me on sp458@kent.ac.uk. I can then post them to the blog for us all to enjoy!

Summary of Discussion on Rain

Posted by Sarah

Our post-screening discussion ranged widely and encompassed: analysis of Joan Crawford/Sadie’s first appearance; Sadie’s costume, especially compared to the other female characters; Crawford’s performance – in particular the many layers of performance; a comparison between Mildred in Of Human Bondage and Sadie in Rain; noting of Crawford and Bette Davis’ contrasting acting styles; Sadie’s antagonistic relationship with the reformer Davidson; Walter Huston’s performance; the film’s happy ending. Throughout discussion was illuminated by reference to Maugham’s short story and the 1928 silent version of the film which starred Gloria Swanson.

We began with discussion of one of the film’s most memorable moments: Joan Crawford’s first appearance. It is especially significant in terms of female representation that Crawford/Sadie is introduced by shots of her body, which themselves are fragmented. (See Laura Mulvey’s ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ for more on the fragmented female body and the ‘male gaze’[i].) First Crawford/Sadie’s right, heavily bangled, hand almost thumps a door post. This is quickly followed by a shot of her left hand making a similar gesture towards the opposite door post. Then her right foot is planted heavily on the ground. A similar action shortly occurs with the left. This is more than the usual star entrance as it makes such a bold statement. Indeed the character/star punctuates the scene with the forceful movement of her limbs. In addition, the stance this pose would constitute if we were to see it in full looks incredibly ungainly, with Crawford/Sadie’s feet seemingly planted quite firmly apart. As such it appears less than ladylike. Finally a shot of Crawford/Sadie’s face gives us a view of her insolently sulky mouth which is accentuated by the heavily outlined lips. Through Crawford/Sadie’s dangling cigarette she utters her first word, a huskily intoned ‘Boys’. It is an astonishingly powerful, and not at all subtle, introduction of both the star (Crawford) and the character (the prostitute Sadie). It was mentioned that a similar scene does not occur in the 1928 silent film starring Gloria Swanson.

We began with discussion of one of the film’s most memorable moments: Joan Crawford’s first appearance. It is especially significant in terms of female representation that Crawford/Sadie is introduced by shots of her body, which themselves are fragmented. (See Laura Mulvey’s ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ for more on the fragmented female body and the ‘male gaze’[i].) First Crawford/Sadie’s right, heavily bangled, hand almost thumps a door post. This is quickly followed by a shot of her left hand making a similar gesture towards the opposite door post. Then her right foot is planted heavily on the ground. A similar action shortly occurs with the left. This is more than the usual star entrance as it makes such a bold statement. Indeed the character/star punctuates the scene with the forceful movement of her limbs. In addition, the stance this pose would constitute if we were to see it in full looks incredibly ungainly, with Crawford/Sadie’s feet seemingly planted quite firmly apart. As such it appears less than ladylike. Finally a shot of Crawford/Sadie’s face gives us a view of her insolently sulky mouth which is accentuated by the heavily outlined lips. Through Crawford/Sadie’s dangling cigarette she utters her first word, a huskily intoned ‘Boys’. It is an astonishingly powerful, and not at all subtle, introduction of both the star (Crawford) and the character (the prostitute Sadie). It was mentioned that a similar scene does not occur in the 1928 silent film starring Gloria Swanson.

The costume was also commented upon at length. Crawford/Sadie wore a tight gingham dress, with a wide white belt further accentuating her curves, for much of the film. The accessories worn at this point, and a little further into the film, are of great significance. Despite the stifling heat of the island, Sadie has a fur draped around her neck and a hat which resembled swan feathers covering most of her head. Sadie is clearly a woman who cares about appearances, and indeed her own performance in everyday life.

Crawford/Sadie’s first appearance is memorable not just due to the energy and the  somewhat startlingly heavily made up face, but the fact a very similar scene occurs towards the film’s end. Before this happens though, Sadie undergoes a spiritual and physical transformation. She is seen with minimal make-up, brushed-out hair and wearing darker, more modest clothes. When she reverts back to type this is reflected by the return to her previous outfit, make-up and hairstyle. This is a great example of Jane Gaines’ assertion that dress often tells the woman’s story.[ii] Crawford/Sadie is re-introduced by shots which once more fragment her body. It was also noted that Crawford/Sadie’s costume marks her out from the other women in the film – the actresses Beulah Bondi and Kendall Lee playing the characters Mrs Davidson

somewhat startlingly heavily made up face, but the fact a very similar scene occurs towards the film’s end. Before this happens though, Sadie undergoes a spiritual and physical transformation. She is seen with minimal make-up, brushed-out hair and wearing darker, more modest clothes. When she reverts back to type this is reflected by the return to her previous outfit, make-up and hairstyle. This is a great example of Jane Gaines’ assertion that dress often tells the woman’s story.[ii] Crawford/Sadie is re-introduced by shots which once more fragment her body. It was also noted that Crawford/Sadie’s costume marks her out from the other women in the film – the actresses Beulah Bondi and Kendall Lee playing the characters Mrs Davidson  and Mrs Macphail. The clothes of the latter pair are more modest than Sadie’s and tend to be in blocks of one colour in contrast to the gingham patterned dress. Similar delineation between the female characters also occurred with Davis/Mildred in Of Human Bondage in relation the actresses Kay Johnson and Frances Dee who play Philip’s other love interests Norah and Sally.

and Mrs Macphail. The clothes of the latter pair are more modest than Sadie’s and tend to be in blocks of one colour in contrast to the gingham patterned dress. Similar delineation between the female characters also occurred with Davis/Mildred in Of Human Bondage in relation the actresses Kay Johnson and Frances Dee who play Philip’s other love interests Norah and Sally.

Crawford’s performance also prompted much discussion. It was noted that physically  she looked quite a bit like Gloria Swanson at certain points. Lies revealed that this might well have spilled over into performance too as Crawford had yet to find her style and imitated Swanson’s earlier portrayal. Indeed comparisons between Crawford and other female stars in melodramas (primarily Swanson and Davis) were found to be useful in examining Crawford’s performance. This

she looked quite a bit like Gloria Swanson at certain points. Lies revealed that this might well have spilled over into performance too as Crawford had yet to find her style and imitated Swanson’s earlier portrayal. Indeed comparisons between Crawford and other female stars in melodramas (primarily Swanson and Davis) were found to be useful in examining Crawford’s performance. This  is made easier by the fact Of Human Bondage and Rain contain several parallels. Both are based on Somerset Maugham stories and were produced at a similar time (1932 and 1934). In addition both the female characters are prostitutes for at least some of the narrative, and marked something of a departure for Davis and Crawford. There are, however, several big differences between the performances of Davis and Crawford, and the characters they play.

is made easier by the fact Of Human Bondage and Rain contain several parallels. Both are based on Somerset Maugham stories and were produced at a similar time (1932 and 1934). In addition both the female characters are prostitutes for at least some of the narrative, and marked something of a departure for Davis and Crawford. There are, however, several big differences between the performances of Davis and Crawford, and the characters they play.

Crawford is required to perform on several levels. There is the bold front Sadie assumes as the prostitute joking with potential clients – brazenly drinking whisky straight out of the bottle in public and dancing with abandon. Sadie’s insincere acknowledgment of her sins is juxtaposed with her contrasting sincere repentance. When Sadie finally reverts to type, this bears similarities to her very first appearance also has significant differences. We particularly noted the transformation scene in which Sadie gains religious enlightenment. Its importance is indicated through the staging on the main staircase (important to several melodramas) and the camerawork. Sadie’s adversary, the religious reformer Alfred Davidson (Walter Huston) stands solidly at the top of the stairs while Sadie looks up from the bottom. She climbs the stairs, ready to take him to task. There is little movement apart from the ascension of the stairs, though Crawford/Sadie’s worrying of the top banister indicates her distress. She descends the steps and appears ready to go. Davidson is seen is close shot standing still and a cut to Sadie reveals that she is also riveted to the spot. The moment in which Sadie is  transformed occurs shortly after and is visible onscreen. The camera lingers on her beautifully lit, tear-stained face as a look of realisation starts in her eyes and then spreads across her features. The camera then moves out to give a better view of Sadie and Davidson, now pictured together in the shot. The scene ends with an attention-pulling crane shot which exits the building.

transformed occurs shortly after and is visible onscreen. The camera lingers on her beautifully lit, tear-stained face as a look of realisation starts in her eyes and then spreads across her features. The camera then moves out to give a better view of Sadie and Davidson, now pictured together in the shot. The scene ends with an attention-pulling crane shot which exits the building.

There is further opportunity for Crawford to show her acting skills. When William Gargan’s character O’Hara (referred to as ‘Handsome’ by Sadie – another example of her playing the gallery) soon returns to take Sadie away to a new life Crawford plays the scene rather robotically to start with. She speaks in a monotone and refuses to look at O’Hara/Gargan. Total disengagement is not possible though as Handsome continues and Sadie briskly pushes him away, raising her voice as she does do. Crawford ably performs Sadie’s conflicting desires as she struggles to resist temptation. The shift between the obvious exaggerated performance Sadie puts on for the surrounding men and the more quiet moments (which occur later on in the film when we first see her alone) help to create a complex and sympathetic character. It was mentioned that perhaps the shifts between different levels of performance by Crawford were what led to the negative contemporaneous critical reviews. Though, as Lies noted, Crawford’s performance has been viewed more favourably since. (Apparently there is still little written on Rain, and pre-code Joan, however.)

There is further opportunity for Crawford to show her acting skills. When William Gargan’s character O’Hara (referred to as ‘Handsome’ by Sadie – another example of her playing the gallery) soon returns to take Sadie away to a new life Crawford plays the scene rather robotically to start with. She speaks in a monotone and refuses to look at O’Hara/Gargan. Total disengagement is not possible though as Handsome continues and Sadie briskly pushes him away, raising her voice as she does do. Crawford ably performs Sadie’s conflicting desires as she struggles to resist temptation. The shift between the obvious exaggerated performance Sadie puts on for the surrounding men and the more quiet moments (which occur later on in the film when we first see her alone) help to create a complex and sympathetic character. It was mentioned that perhaps the shifts between different levels of performance by Crawford were what led to the negative contemporaneous critical reviews. Though, as Lies noted, Crawford’s performance has been viewed more favourably since. (Apparently there is still little written on Rain, and pre-code Joan, however.)

By contrast, while Davis’ performance in Of Human Bondage is by no means on one-level, we rarely get a glimpse of different aspects of what might be considered the ‘real’ Mildred. Of course the notion of a ‘real’ character is a very fraught and abstract concept, more so when star image is added to the mix. Here it is very noticeable though, since Mildred the character is always performing; she puts on an accent and gives herself airs to appear more refined and she manipulates Philip, and other men, by exaggerated dismissive gestures or flirtatious behaviour. In addition, Davis/Mildred is always moving – facially and bodily – a whole performance in itself. There are two main scenes in Of Human Bondage when Mildred is not performing. The first is the tirade she unleashes  against Philip which is very physical and exaggerated. The second is the unglamorous scene in which she is seriously ill and escorted from her lodging to hospital. Here she is incapable of moving much. In both of these scenes Mildred’s real self is revealed as truly horrible: in the first her vindictive character is fully vented and in the second she is physically hideous.

against Philip which is very physical and exaggerated. The second is the unglamorous scene in which she is seriously ill and escorted from her lodging to hospital. Here she is incapable of moving much. In both of these scenes Mildred’s real self is revealed as truly horrible: in the first her vindictive character is fully vented and in the second she is physically hideous.

We found it interesting that there was such a variance between Crawford’s, at times, fairly restrained playing with little movement and Davis’s constant movement and big gestures in these two melodramas. Especially because melodrama is a genre in which performance is often thought to be related to exaggeration. Lies highlighted the difference between Crawford’s naturalistic and Davis’ theatrical approaches. In addition, it was thought that Crawford’s instinctive playing coincided with Sadie’s almost primitive awareness of danger. As soon as, at first sight, Sadie sees Davidson looking intently at her she appears to recognise the danger, first returning the look and then glancing down. The different types of performances are also related to the fact that while Davis is seen primarily as an actress, Crawford is largely remembered as a star with little range.

Of course part of the difference is due to the characters and the fact that while Mildred is not the central character in Of Human Bondage, Sadie is Rain’s protagonist. There are many other Crawford and Davis performances in melodramas available for us to compare and contrast to get a better idea of trends. (This could be a very fruitful, and enjoyable, line for future screenings!) It reveals that as well as the infinite variety of melodrama which has been evident in our screenings (male melodrama, animation, theatrical adaptations, Honk Kong cinema etc), even this rather narrow subgenre of melodrama, the Woman’s Film, is diverse.

In addition to the sympathy created by Crawford’s performance, it was noted that the film, like the short story, promoted Sadie’s position as the correct one. The Doctor, who is central in Maugham’s story, is seen to be sympathetic to her plight. But he is not the main male character in the film, neither is this role filled by Crawford/Sadie’s love interest Handsome: instead the reformer Davidson takes centre stage. His anguish in his moment of weakness is one of the film’s key moments. As well as being pictured (it was only ever implied in the story) this is heightened by the film’s wonderfully atmospheric use of sound. The beating of rain which has been persistent for much of the film reaches its pitch and is accompanied by diegetic drumming. Contrast is present between the changeability in Crawford/Sadie’s performance and situation and Davidson’s immovable morality. Huston conveys this formidably, with a stolidly still uprightness in which the framing colludes.

In addition to the sympathy created by Crawford’s performance, it was noted that the film, like the short story, promoted Sadie’s position as the correct one. The Doctor, who is central in Maugham’s story, is seen to be sympathetic to her plight. But he is not the main male character in the film, neither is this role filled by Crawford/Sadie’s love interest Handsome: instead the reformer Davidson takes centre stage. His anguish in his moment of weakness is one of the film’s key moments. As well as being pictured (it was only ever implied in the story) this is heightened by the film’s wonderfully atmospheric use of sound. The beating of rain which has been persistent for much of the film reaches its pitch and is accompanied by diegetic drumming. Contrast is present between the changeability in Crawford/Sadie’s performance and situation and Davidson’s immovable morality. Huston conveys this formidably, with a stolidly still uprightness in which the framing colludes.

We also observed the way Sadie was contrasted to other characters, especially the female ones. While the Doctor’s wife, like him, is low-key, Mrs Davidson is as aggressive as her husband in demanding Sadie’s salvation. Mrs Davidson is shown to be vindictive, rather than Christian, in her attitude though. She exaggerates when telling her husband that Sadie spoke back to her. We also thought it was fascinating that Mrs Davidson is the subject of the film’s last shot. After Sadie walks off with Handsome (a happy ending not present in the story, but almost obligatory in Hollywood narratives) the camera stays with the newly-widowed Mrs Davidson clasping her hands to her face.

We also observed the way Sadie was contrasted to other characters, especially the female ones. While the Doctor’s wife, like him, is low-key, Mrs Davidson is as aggressive as her husband in demanding Sadie’s salvation. Mrs Davidson is shown to be vindictive, rather than Christian, in her attitude though. She exaggerates when telling her husband that Sadie spoke back to her. We also thought it was fascinating that Mrs Davidson is the subject of the film’s last shot. After Sadie walks off with Handsome (a happy ending not present in the story, but almost obligatory in Hollywood narratives) the camera stays with the newly-widowed Mrs Davidson clasping her hands to her face.

While Sadie does have a happy ending, which in some ways domesticates her, we thought it significant that she still appears in many ways similar to the Sadie we saw at the very start of the film. We concluded our discussion by mentioning how unusual it was for a sinning Hollywood heroine to end a film unreformed, especially after the  stricter policing of the Hays Code in 1934. Two films starring Barbara Stanwyck are good examples of pre and post-code attitudes to female character and crime. In the pre-code The Miracle Woman (1931) we see Florence Fallon

stricter policing of the Hays Code in 1934. Two films starring Barbara Stanwyck are good examples of pre and post-code attitudes to female character and crime. In the pre-code The Miracle Woman (1931) we see Florence Fallon  move from con artist evangelist to member of the Salvation Army. This clearly contrasts to Rain’s treatment of Sadie. Unsurprisingly, Stanwyck’s character Lee Leander in a later film, Remember the Night (1940), is punished for her shoplifting crimes by being sent to prison.

move from con artist evangelist to member of the Salvation Army. This clearly contrasts to Rain’s treatment of Sadie. Unsurprisingly, Stanwyck’s character Lee Leander in a later film, Remember the Night (1940), is punished for her shoplifting crimes by being sent to prison.

Many thanks to Lies for providing such a wonderful introduction to Joan and Rain.

[i] Mulvey, Laura. “Visual pleasure and narrative cinema.” Feminisms: an anthology of literary theory and criticism (1975): 438-48.

[ii]Gaines, Jane. “Costume and Narrative: how dress tells the woman’s story.” Fabrications: costume and the female body (1990): 180-211.

Do, as always, log in to comment or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk

Melodrama Readings: Gledhill and Williams

Posted by Sarah

I thought it would be useful to draw attention to some excellent chapters about film and melodrama by two of the field’s leading writers on the subject.

These are:

Christine Gledhill’s “Rethinking Genre” in Linda Williams and Christine Gledhill, eds, Reinventing Film Studies. Bloomsbury USA Academic, 2000: 42-88.

and

Linda Williams’ “Melodrama Revised” in Nick Browne, ed, Refiguring American Film Genres: History and Theory, University of California Pr, 1998: 42-88.

Please go to http://melodramaresearchgroupextra.wordpress.com/ for more details.

I’m sure you’ll find it interesting to (re)read them. As always, do log in to comment or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk

Melodrama Readings: Bourget and Basinger

Posted by Sarah

Ahead of this week’s screening of Joan Crawford in Rain, Lies has very kindly suggested some readings for this week.

These are:

“Faces of the American Melodrama: Joan Crawford” in Film Reader 3 (1978), by Jean-Loup Bourget and Chapter 5 of Jeanine Basinger’s A Woman’s View: How Hollywood Spoke to Women, 1930-1960. Wesleyan University Press, 1995, pp. 160-187. (Pages 164-177 are most relevant for discussion of Crawford and Davis.)

Please go to http://melodramaresearchgroupextra.wordpress.com/ for more information.

As always, do log in to comment, or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk to add your thoughts.

Melodrama Screening and Discussion, 16th October, Keynes Seminar Room 6, 4-7pm

Posted by Sarah

All are welcome to attend the second of this term’s screening and discussion sessions which will take place on the 16th of October in Keynes Seminar Room 6, from 4pm to 7pm.

We will be screening Lies’ choice: Rain (1932, Lewis Milestone, 94 mins)

Lies has very kindly provided the following introduction:

Joan Crawford and Rain

Rain, based on W. Somerset Maugham’s short story Miss Sadie Thompson, deals with the adventures of a group of travelers who are temporarily stranded on the South Pacific island of Pago Pago. As young prostitute Sadie Thompson (Joan Crawford), wanted in America for a crime that is never named, spends her time socializing with the US marines posted on the island, she becomes a thorn in the eye of fanatical preacher Alfred Davidson (Walter Huston), who decides she needs salvation.

Although Joan Crawford was one of the key box office stars for the year 1932, the film was not a major hit at the time; Variety wrote that “It turns out to be a mistake to have assigned the Sadie Thompson role to Miss Crawford. It shows her off unfavorably. The dramatic significance of it all is beyond her range.” Motion Picture was kinder and pointed out that “a picture with such a long stage and screen history behind it starts with a handicap of inevitable comparisons”, calling Crawford “neither the greatest ‘Sadie Thompson’ of theatrical history, nor the worst by any means”. This review touches upon an important consideration in terms of Rain as a film, which is the fact that the story had previously been made into a play (1923) and into a silent film (1928, as Sadie Thompson). It would also be remade in 1953 with Rita Hayworth in the title role as Miss Sadie Thompson.

Although Joan Crawford was one of the key box office stars for the year 1932, the film was not a major hit at the time; Variety wrote that “It turns out to be a mistake to have assigned the Sadie Thompson role to Miss Crawford. It shows her off unfavorably. The dramatic significance of it all is beyond her range.” Motion Picture was kinder and pointed out that “a picture with such a long stage and screen history behind it starts with a handicap of inevitable comparisons”, calling Crawford “neither the greatest ‘Sadie Thompson’ of theatrical history, nor the worst by any means”. This review touches upon an important consideration in terms of Rain as a film, which is the fact that the story had previously been made into a play (1923) and into a silent film (1928, as Sadie Thompson). It would also be remade in 1953 with Rita Hayworth in the title role as Miss Sadie Thompson.

Crawford herself appears to have been on Variety’s side, and said in later years that she hoped “they burn every print of this turkey that is in existence”. She blamed the film’s issues on its writer and director, as well as on her younger self, who “took the bull by the horns and did my own Sadie Thompson. I was wrong every scene of the way”[1]. Despite this judgment even by its star, however, the film is one of Joan Crawford’s better-remembered early performances today.

Since both Of Human Bondage and Rain were written by the same author and made, as films, around the same time, they lend themselves quite well to a comparison of the performances and stardom of Bette Davis and Joan Crawford. These two stars have frequently been grouped together as similar types – both often playing, as Basinger puts it, “exaggerated”, extraordinary women, particularly in their later careers[2] – yet have also often been contrasted with each other as “the actress” (Davis) and “the star” (Crawford).

To watch (or re-watch) Crawford in Rain: http://archive.org/details/rain1932

Link to the original short story:

http://maugham.classicauthors.net/Rain/

Link to the Swanson film:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qWtW_RqSwAk&list=PL272B5585907AB161

Connected to last week’s question on radio versus film melodrama, how might melodramatic performance differ from silent to sound film? Is silent film, with its reliance on gesture and facial expression, particularly suited to the genre?

Summary of Discussion on Of Human Bondage

Posted by Sarah

Our first post-screening discussion after the lengthy Summer Break was lively, and encompassed several areas relating to melodrama, this specific film and Bette Davis. It included comment on: Bette Davis’ performance; the film as an adaptation of Somerset Maugham’s novel; the film’s music; comparison of the female characters; later adaptations of the novel; stars Leslie Howard and Bette Davis’ other work together; Somerset Maugham as a writer.

Unsurprisingly the discussion began with comments on Davis’ tour de force performance. Davis’ ability to convey Mildred Rogers’ attempts to appear more refined through her voice was deemed especially effective. She shifted effortlessly, and at the appropriate moments, between strangulated cockney and strangulated cockney with a slight hint of unconvincing cultivation. This undulating movement was also present in Davis’ physical performance. This was quite exaggerated. Using gestures and facial expressions liberally, Davis wonderfully conveyed both Mildred’s flirtatious nature and her at times pointedly indifferent attitude to Philip. We especially noted Davis’ use of  her eyes to express these contradictory aspects of Mildred’s character. Occasionally Mildred with her head tipped down, steadily and flirtatiously looked up at Philip across the top of her champagne glass (see picture on right). More often though, she flicked her eyes away from him, either quickly or slowly, to signal her disagreement with him or to reveal that she was mulling over an offer he had made.

her eyes to express these contradictory aspects of Mildred’s character. Occasionally Mildred with her head tipped down, steadily and flirtatiously looked up at Philip across the top of her champagne glass (see picture on right). More often though, she flicked her eyes away from him, either quickly or slowly, to signal her disagreement with him or to reveal that she was mulling over an offer he had made.

Despite the fact that throughout the film Davis employed theatrics, and could hardly be described as restrained, her two big scenes were stunningly effective. In Mildred’s tirade against Philip, which we discussed at length, Davis ratcheted her performance up a gear. There is constant movement in this scene. Both by Davis, who turns to and away from the camera whilst striding away from it, and by the camera itself which follows Davis at some speed. Extra impetus was added by the fact that the scene was fairly quiet up to this point. It was also the first time we saw Mildred really furious. This was prompted by Philip’s comment that Mildred disgusts him. This, in turn, was in response to her attempt to seduce him. After repeating Philip’s words with her voice and body shaking with disbelief and anger, the scene reaches its climax as Davis performs a violent gesture. She tells Philip that every time he has kissed her she wiped her mouth. Mildred clearly thinks this is a useful phrase to torment Philip with, and she repeats it, at

Despite the fact that throughout the film Davis employed theatrics, and could hardly be described as restrained, her two big scenes were stunningly effective. In Mildred’s tirade against Philip, which we discussed at length, Davis ratcheted her performance up a gear. There is constant movement in this scene. Both by Davis, who turns to and away from the camera whilst striding away from it, and by the camera itself which follows Davis at some speed. Extra impetus was added by the fact that the scene was fairly quiet up to this point. It was also the first time we saw Mildred really furious. This was prompted by Philip’s comment that Mildred disgusts him. This, in turn, was in response to her attempt to seduce him. After repeating Philip’s words with her voice and body shaking with disbelief and anger, the scene reaches its climax as Davis performs a violent gesture. She tells Philip that every time he has kissed her she wiped her mouth. Mildred clearly thinks this is a useful phrase to torment Philip with, and she repeats it, at increased volume. Davis also emphasises the point by ferociously rubbing her arm across her heavily lipsticked mouth. It is notable that while the gesture is arguably one of the film’s most memorable moments, partly due to Davis’ heightened performance, it does not appear in the novel.

increased volume. Davis also emphasises the point by ferociously rubbing her arm across her heavily lipsticked mouth. It is notable that while the gesture is arguably one of the film’s most memorable moments, partly due to Davis’ heightened performance, it does not appear in the novel.

What made it unforgettable is that as Mildred is shouting angrily with mad, staring eyes, she is also smiling, or perhaps more correctly, grimacing. She clearly relishes having the opportunity to express her true feelings to Philip. This was compared to other moments in Davis films when her characters’ real self is unleashed, for example In This Our Life (1942, John Huston).

Davis’ other ‘big’ scene revealed more of Mildred’s vindictiveness. This is very possibly even worse than her spontaneous reaction to Philip’s comment as she has had time to consider her actions. She gleefully rampages through Philip’s apartment, destroying the works of art which mean the most to him, but which she has declared she finds vulgar.The music which accompanies the following scene is revealing. Mildred coolly picks up ‘baby’ from her cot in preparation of them both leaving Philip’s apartment. There is a ‘frowsy’, almost comedic, quality to the music. While the audience has never entertained the same illusions about Mildred as Philip has, it suggests that after her tirade and the following rampage the film is now signalling through music that her real nature is indeed shabby. It was mentioned that apparently after the first screening of the film, some of its music was changed as it was considered too comedic in places.

Our focus on performance, and in particular specific moments of heighted emotion and gesture was related to some of the discussion we engaged in at our previous screening sessions. Of special interest, and worthy of further consideration, is how these instances are juxtaposed with elements of restraint.

As with some of our previous discussions, we spoke about the suffering woman. While the film showcased Davis’ performance, it was perhaps less about Mildred’s suffering than Philip’s. This is similar to the source novel. Much of its 700 pages detailed Philip’s childhood, his time spend living abroad, his medical training and his later search for employment. Unsurprisingly the 83 minute film dispensed with much of the novel’s plot. The fact it chose to focus on Philip and Mildred as its main characters was testament to the pernicious effect Mildred had on Philip and clearly related to Hollywood’s privileging of the romantic couple.

As with some of our previous discussions, we spoke about the suffering woman. While the film showcased Davis’ performance, it was perhaps less about Mildred’s suffering than Philip’s. This is similar to the source novel. Much of its 700 pages detailed Philip’s childhood, his time spend living abroad, his medical training and his later search for employment. Unsurprisingly the 83 minute film dispensed with much of the novel’s plot. The fact it chose to focus on Philip and Mildred as its main characters was testament to the pernicious effect Mildred had on Philip and clearly related to Hollywood’s privileging of the romantic couple.

Philip’s other romantic relationships

Philip’s other romantic relationships  (with Norah, played by Kay Johnson, left, and Sally, played by Frances Dee, right) were given little screen time, not really enough to compete with Mildred’s central position. The female characters and performances other than Mildred/Davis were very restrained. Other characters (such as Dr Jacobs, the medical student Griffiths and especially the flamboyant Athelny) were sketched more broadly. We thought these characterisations probably lacked depth because they were given very little time to make their impression. It is perhaps also telling that these are all played by male actors – Desmond Roberts, Reginald Denny and Reginald Owen respectively. While the performance styles differ to the lesser female characters, they also supply contrast to Davis and Howard’s more nuanced portrayals.

(with Norah, played by Kay Johnson, left, and Sally, played by Frances Dee, right) were given little screen time, not really enough to compete with Mildred’s central position. The female characters and performances other than Mildred/Davis were very restrained. Other characters (such as Dr Jacobs, the medical student Griffiths and especially the flamboyant Athelny) were sketched more broadly. We thought these characterisations probably lacked depth because they were given very little time to make their impression. It is perhaps also telling that these are all played by male actors – Desmond Roberts, Reginald Denny and Reginald Owen respectively. While the performance styles differ to the lesser female characters, they also supply contrast to Davis and Howard’s more nuanced portrayals.

Some of the film’s more avant garde touches were also discussed. We noted the straight-to-camera acting of Davis and Howard in particular, during which eyelines did not match and the 180 degree rule was violated. The film’s ending which shows Philip and Sally crossing a busy street was deemed particularly odd. We presume that Philip is telling Sally of Mildred’s death, and the fact he is now free, but the unnecessarily loud traffic noise drowns out the dialogue. There did not seem to be any real reason for this, especially as we had already seen Davis at her most unglamorous as the dying Mildred was collected from her room and taken to hospital.

There was also a dreamlike quality to much of the film, not just during the projection of  Philip’s dreams. The latter afforded a greater opportunity for Davis to display her acting skills as in these Mildred is far more responsive to Philip, especially facially. In his dreams Philip imagines Mildred speaking with Received Pronunciation. As the ‘real’ Mildred, Davis shows Mildred’s doomed attempts to achieve this accent. This is revealing of Philip’s prejudices and it is also notable that in the dream sequences his physical disability has disappeared. This split between reality and dream also effectively highlights the unusual social realism of the film and Hollywood’s usual focus on the glamour of coupledom and romance.

Philip’s dreams. The latter afforded a greater opportunity for Davis to display her acting skills as in these Mildred is far more responsive to Philip, especially facially. In his dreams Philip imagines Mildred speaking with Received Pronunciation. As the ‘real’ Mildred, Davis shows Mildred’s doomed attempts to achieve this accent. This is revealing of Philip’s prejudices and it is also notable that in the dream sequences his physical disability has disappeared. This split between reality and dream also effectively highlights the unusual social realism of the film and Hollywood’s usual focus on the glamour of coupledom and romance.

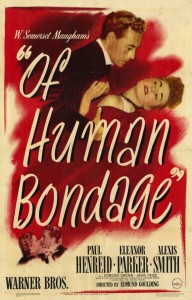

We wondered about later versions of the story. In 1946 Paul Henreid (Davis’ co-star in Now Voyager 1942 and Deception 1946) and Eleanor Parker starred in a Hollywood remake directed by Edmund Goulding (who often collaborated with Davis). Kim Novak and Laurence Harvey starred in the 1964 UK film (see a clip of Mildred’s death scene: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N8iVYV93BYw). Interestingly this was written by Bryan Forbes and partly directed by him (uncredited) alongside the UK’s Ken Hughes and Hollywood’s Henry Hathaway. Forbes is known for his kitchen sink drama The L Shaped Room in 1962.

We wondered about later versions of the story. In 1946 Paul Henreid (Davis’ co-star in Now Voyager 1942 and Deception 1946) and Eleanor Parker starred in a Hollywood remake directed by Edmund Goulding (who often collaborated with Davis). Kim Novak and Laurence Harvey starred in the 1964 UK film (see a clip of Mildred’s death scene: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N8iVYV93BYw). Interestingly this was written by Bryan Forbes and partly directed by him (uncredited) alongside the UK’s Ken Hughes and Hollywood’s Henry Hathaway. Forbes is known for his kitchen sink drama The L Shaped Room in 1962.

This highlights further melodrama and British social realism’s connections, mentioned in last term’s discussion on Love on the Dole (1941).

TV adaptations were made in a 1949 episode of Studio One starring Charlton Heston and Felicia Montealegre (watch the whole episode here:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=klGfU5VKGAc) and as part of Somerset Maugham TV Theatre in 1952. Cloris Leachman appeared as Mildred.

We also discussed Howard and Davis’ other films together. They appeared in The Petrified Forest (1936) and It’s Love I’m After (1937) – both directed by Archie Mayo. While the former could also be described as a melodrama, a gangster melodrama, the latter is a light romantic comedy in which Howard and Davis play a bickering couple. Performance is central to this film too, however as their characters are actors. (Do take a quick look on www.youtube.com for clips and trailers.)

We also discussed Howard and Davis’ other films together. They appeared in The Petrified Forest (1936) and It’s Love I’m After (1937) – both directed by Archie Mayo. While the former could also be described as a melodrama, a gangster melodrama, the latter is a light romantic comedy in which Howard and Davis play a bickering couple. Performance is central to this film too, however as their characters are actors. (Do take a quick look on www.youtube.com for clips and trailers.)

Discussion ended with brief mention of the critical evaluation of Maugham as a novelist.  He is considered by some to be trashy, and this complements Mildred’s character in Of Human Bondage. Unusually for a male author can be considered middlebrow. We will look into this more next week when we screen Rain (1932) which is a screen translation of his 1921 short story.

He is considered by some to be trashy, and this complements Mildred’s character in Of Human Bondage. Unusually for a male author can be considered middlebrow. We will look into this more next week when we screen Rain (1932) which is a screen translation of his 1921 short story.

Many thanks to Ann-Marie for choosing such a wonderful film which certainly gave us plenty to chew over…

As ever, do log in to comment, or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk to add your thoughts.