By Cindy Vallance

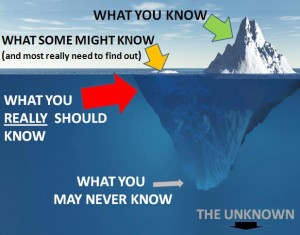

In my recent blog about student blogs, I mentioned that one of the key reasons for the existence of the Social Sciences Change Academy is to recognise and do our utmost, as individuals and as a collective group, to demonstrate the power of bringing together the complementary viewpoints, experiences and capabilities of students, professional services staff and academic staff.

By focusing on activities that demonstrate our commonly shared values, we demonstrate our commitment to a vision of an inclusive yet diverse educational community – one in which everyone is treated with dignity, respect and fairness; an environment in which collaboration and innovation can thrive.

This healthy environment will only develop if we get beyond stereotypes of what it means to be a ‘student’ an ‘academic’ or an ‘administrator.’ One practical way to do this is by listening to others; for instance by tuning in through social media to what students are saying. Another way is to consider the words of John Gill, THE editor, from an article in the Association of University Administrators (AUA) magazine. He states:

“The view that administrators and academics are different beasts who will never get on may still be deeply entrenched in some people’s minds, but it cannot be right in the 21st century. Yes, they are different, and yes, academics will never appreciate intrusive or overbearing management, but when it is supporting the institution, supporting research programmes, and – perhaps most important of all from the point of view of professional services staff – supporting students, then I really don’t see how anyone can object…”

I must, of course, add to this quote that professional services staff will also never appreciate conspicuously uninterested or arrogant academic practice, and that similarly, students appreciate none of these negative qualities; qualities which we see demonstrated on a day-to-day basis more than we might like to admit.

It is up to each of us as individuals to question the received wisdom that has led to these divisions separating ‘us’ and ‘them,’ to constantly challenge these unhelpful behaviours and to work to exemplify their opposites.

If we do not, then all we are left with is empty rhetoric about equality and diversity and a weakened belief in the power of education to change lives in a positive way. And isn’t our belief in the power of education a large part of why we have chosen to be members of a University community in the first place?

Reference: Profile Article: John Gill, THE Editor, AUA Newslink, Issue Number 73.