Organisations are complex places and change can become a complex business. We cannot simply expect to make a change here and see an outcome there; outcomes are rarely as simple as ‘cause and effect’. There are many reasons for this, one of which is the fact that different people will see things (and respond) in different ways.

My last blog presented the basic ideas concerning the ‘theory of knowledge’.

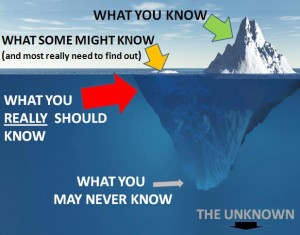

One key point was that although many people can see or know the obvious, often the important knowledge is what is largely unknown (to some degree). We need to look further than just what fictional hotelier Basil Fawlty would call ‘the bleedin’ obvious’.

This means that we must ask the right questions. Deming gives a great example of how to improve performance, describing a children’s charity which raises money for medical care and food support, using appeals run through mailing lists (Deming 1993). He points that final performance (how much money is donated to the charity) is largely unaffected by the efficiency of the steps of printing, mailing, payment, receipt, acknowledgement; improvement effort in these areas will be largely irrelevant. The important step which impacts on the willingness of donors to give money is the quality of the message which has been written to them (and which is formulated right at the start of the process); zero defects in the rest of process is of much less importance. This is where a lot of today’s approaches, like ‘lean’, ‘benchmarking’ and ‘process-re-engineering’ fall down – they encourage people to apply tools to a situation – dealing with the obvious; efficiency, flow and defects, without thinking about purpose and what affects the system as a whole. The result is that, after the initial rush of enthusiasm, people do not see great benefits in the change.

This is a warning to those looking at change – are we fiddling around the edges or are we dealing with fundamental change that will make a real difference?

This is not to say that statements of the obvious are unimportant – we can be blind to things that are abundantly clear to our users. People’s observations and opinions of the obvious are not trivial, the key is to examine what sits behind those phenomena and understand them properly.

In a higher education institution, the notion of involving students, although understood and welcomed can nevertheless be accompanied by a little hesitation or even reservation. This suggests to me a degree of discomfort on the part of staff (Will students understand the constraints that we have to work under? Will they have unrealistic expectations? Can students really understand what they themselves need?). Let’s face it, life would be simpler if we didn’t involve students – but that wouldn’t make things better either. We need to challenge our discomfort, face up to the weaknesses, illogicalities and frustrations that continually haunt our work and face up to the need to think differently and make new efforts.

Why? Because any discomfort we have in involving our users in the change process (whether they are students, partners, clients or customers) probably reveals our unrecognised, unknown or deliberately concealed concerns with how the system is currently under-performing for those very people. It challenges the way we work now and how we should work in the future. Basil Fawlty’s chaotic hotel would be fundamentally improved if he and his wife Sybil really worked out how they could together offer great hospitality to their guests – whereas instead they usually (hilariously and painfully) fiddle around the fringes of service, battling against each other.

So let’s not focus on the obvious and superficial. Deming, himself a well-renowned teacher (he won the US National Medal of Technology 1987 and the National Academy of Science, Distinguished Career in Science award 1987), makes an interesting observation on university teaching “I have seen a teacher hold a hundred and fifty students spellbound, teaching what is wrong. His students rated him as a great teacher. In contrast, two of my own greatest teachers in universities would be rated poor teachers on every count. Then why did people come from all over the world to study with them, including me? For the simple reason that these men had something to teach. They inspired their students to carry on further research” (Deming 1982).

In other words, in some cases the obvious (“a good approach”) masked the fundamentals (“poor content”), whereas the real value lies in delivering what people are really looking for. A university could ask students to rate it on trivial and obvious matters and think it is doing great, when in reality it is letting its students down – do we always ask the right questions?

Now that would be a challenge for change…

Read more here:

Deming W.E. (1982) Out of the Crisis, MIT CAES, Cambridge MA.

Deming W.E. (1993) The New Economics, MIT CAES, Cambridge MA.