If we want to see change happen, and for it to occur in a meaningful, timely and impactful manner, we need to see any resistance that we encounter in a different light. Rather than considering resistance an unhelpful roadblock to change, we should perhaps see it (at risk of supplying any more old clichés) as both an opportunity and an indicator of progress. The opportunity is that resistance opens a door to new dialogue with others. As an indicator, resistance shows us that people are noticing what we are doing.

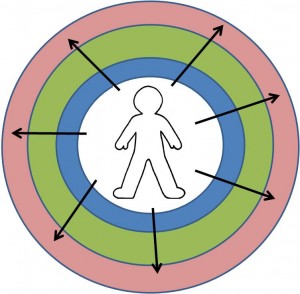

As Herrero (2006) points out, the assertion that “People are resistant to change” is untrue. The reality is that people are resistant to change if nothing in terms of what managers expect from them changes. Extending that notion, Seddon (2005) suggests that the reason people are resistant to change is that they often don’t see its relevance to their work, because the rest of the system – how they are managed, doesn’t change. With the right encouragement these people can identify and discuss the other areas where change might be required – and themselves, with the right support, start to influence that wider change.

It is too easy to assume that “there will always be casualties – people not accepting change – and you need to identify and deal with them.” Hererro does not accept this and also suggests that we need to reject the position that “skeptical people and enemies of change need to be sidelined.”

Instead when we manage change, Herrero suggests that greater care is required;

- don’t assume that people have excluded themselves.

- expect resistant behaviours to disappear when alternatives are reinforced.

- give sceptics a bit of slack (they may well have something to contribute).

- suspend judgement, be willing to be surprised, and don’t write people off too quickly.

We should also recognise that discord provides opportunity for debate and the development of new ideas. We always need to examine what these ‘outsiders’ are saying and learn from them what the issues or problems really are. Neither should we expect “People used to not complying with norms will be even worse at accepting change.” With viral change, Herrero encourages different routes to establishing new norms and for these approaches, ‘non-normative’ people often make good champions.

This means that anyone involved in change, at whatever level, needs to take on responsibility for getting on with the change, to be seen to do the things we want to see done. We need to be open minded and able to discuss and debate effectively, not quash dissent, but seek opportunities for engaging new ideas.

Rather than challenging the nay-sayers with a dogma that ‘resistance is useless’ perhaps we should have a new perspective that will engage their input: resistance is useful!

Read more…

Herrero, L. (2006) Viral Change, meetingminds, UK.

Seddon, J. (2005) Freedom from Command and Control, Vanguard Press, Buckingham, UK.

I totally agree that resistance is useful as it can often act as a “reality check” on over zealous or ill thought through plans . Some times people are perceived as being “awkward” when in fact they know more than the project manager of what is required in the tasks affected and systems to be changed. Very often they will have good ideas about potential alternative changes. In my experience, very often the “awkward” people have the most to contribute if encouraged and listened to. The real problems arise when people are already disengaged with the institution or role that they occupy.

Thank you for your observations. It is often worth reminding colleagues who lead and manage change that ‘behind every moan is a potentially useful idea’. At an individual level, if we get better at listening to people and look for mutual benefits and outcomes (a win-win mindset) it can change our views of what is possible and can accelerate improvements.

I hope that you continue to dip into our other blogs and we look forward to your future comments.