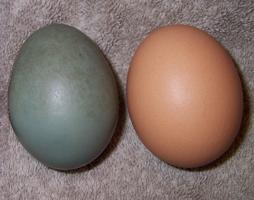

One item is ovoid, solid, brown, less than 10cms tall; another is about the same size and shape but a striking blue. Here are the two items; similar, but different. Lets take the one on the right – is it an egg? Yes it looks like an egg, but what about the second – is it an egg? Probably? Possibly? But what about that colour? Maybe the shape is not quite right too.

A perceptive person may seek out other information:

• is each item heavy or light? – actually they both weigh the same, about 60 grammes;

• are they rough or smooth? – generally smooth, but both are slightly matt to the touch;

• cold or hot ? – both are cold, but warm up easily enough in your hands

Who cares?

When my 12-year-old son is feeling cheeky, and thinks that he can catch me unawares, he will secretly pick up one of these, suddenly shout ‘hey Dad!’ and throw it at me to test my reflexes. He knows that he will get a reaction – I might laugh, get cross, duck, catch it, jump out the way or use any combination of these behaviours.

And what happens if it hits me or I drop it? With the brown one – well, nothing ; no mess at all because despite being the right shape, colour, weight and texture of a chicken egg it is rubber. Until it bounces off the floor you would never really know, even if you look at it closely. However, the strange blue egg will make a terrible mess. It is of course a duck egg. Thankfully my son has never tried to throw one of the blue eggs at me!

When we say we ‘manage by fact‘ what do we really mean? The facts are obvious aren’t they? Like the eggs, facts are probably not obvious – we usually work on the basis of our best ‘knowledge’ and that knowledge can be very variable. Knowledge ranges from pure facts to pure guesses; from fixed perceptions and preconceptions to a broad balance of possibilities; from empirical evidence to ‘belief’. The most surprising thing is that, to some degree or another, none of these things are necessarily ‘better’ or ‘worse’; ‘right’ or ‘wrong’.

A belief might be well founded, based on experience or relate to something that is essentially unmeasurable or unknowable – we have to go with a reasoned belief. The problems arise when people use beliefs (and I am not talking about religious beliefs) in the face of contradictory, reliable evidence.

For example, if a manager believes people are motivated solely by money, that manager does not have helpful knowledge of motivation and will therefore end up working with people in unhelpful ways (for them and, ultimately, for the manager too). The evidence concerning what motivates people at work is out there and should be sought by that manager, be understood and applied.

In another case a person may believe that female workers are more efficient than male workers, so that person’s behaviour towards workers of different genders may end up being distorted and again will ultimately be unhelpful.

At the other  end of the scale we have facts; and ‘knowledge of facts’ can equally be an area of difficulty. Surely, if sales this month are up 10% on the same month last year, that’s a fact – but what does the 10% difference really mean (and I am not getting philosophical here)? Look at the diagram here – one person might see the last data point circled in red for February as great performance compared to Feburary in the previous year; others might be less sure.

end of the scale we have facts; and ‘knowledge of facts’ can equally be an area of difficulty. Surely, if sales this month are up 10% on the same month last year, that’s a fact – but what does the 10% difference really mean (and I am not getting philosophical here)? Look at the diagram here – one person might see the last data point circled in red for February as great performance compared to Feburary in the previous year; others might be less sure.

As for the rubber egg – seeing that as a real egg is surely wrong (other than for use as a ball to bounce at your Dad perhaps)? Well not exactly. If you want to collect eggs from a broody hen, it is important that you replace her freshly laid egg with a replica that is such a good copy that she is convinced that it is a real egg. Now what does that mean for management by facts?

Further reading:

Aguayo R. 1990, Dr Deming: The American who taught the Japanese About Quality, Mercury, London.

MacDonald, J. (1998) Calling a Halt to Mindless Change, Amacom, UK