The world is, alas, not straightforward – choices are hard, mistakes are made, doubts are cast and events in the past shape and often warp the future; all elements captured in Mercy Killing, by crime writer and real-life detective, Lisa Cutts. Centred around the murder of a known paedophile, Cutts deliberately muddies the waters throughout the novel, crafting a story that makes the reader’s reactions to characters less than straightforward, playing on our unease.

What Cutts is exploring in the novel, a gritty, urban police procedural informed by her own experiences as an investigating detective, is the idea that bad things can come from good intentions, a concept which affects all the characters involved in the drama, and which sees each of them grappling with their own conflicts and making uncomfortable liaisons. At the head of the case, DI Powell is fully aware that, to solve the case, he must ‘break bread with a monster,’ and knows precisely the moment when he crosses the line. His personal dance with the devil involves a meeting with the less than wholesome Martha, who leads the Volunteer Army, a group of local people which at first seems to have a positive mandate – those involved are ‘trying to make it as safe for people as they can about living with sex offenders around them and we want to work with the police. We’re trying to do our bit to help.’ Yet urban vigilantes taking the law into their own hands is never a good idea, and later in the book the reason for the creation of the group is revealed, arising as it does from yet another evil beginning.

What Cutts is exploring in the novel, a gritty, urban police procedural informed by her own experiences as an investigating detective, is the idea that bad things can come from good intentions, a concept which affects all the characters involved in the drama, and which sees each of them grappling with their own conflicts and making uncomfortable liaisons. At the head of the case, DI Powell is fully aware that, to solve the case, he must ‘break bread with a monster,’ and knows precisely the moment when he crosses the line. His personal dance with the devil involves a meeting with the less than wholesome Martha, who leads the Volunteer Army, a group of local people which at first seems to have a positive mandate – those involved are ‘trying to make it as safe for people as they can about living with sex offenders around them and we want to work with the police. We’re trying to do our bit to help.’ Yet urban vigilantes taking the law into their own hands is never a good idea, and later in the book the reason for the creation of the group is revealed, arising as it does from yet another evil beginning.

DC Sophia Ireland’s own stance on pursuing criminals neatly outlines the whole moral dilemma of the book: ‘we can’t live in a society that thinks it’s ok to kill them off without so much as a trial.’ She has a firm grasp of the the crux of the book right there – the battle between justice and righteousness. But she in turn has an internal conflict: she is not convinced that DC Gabrielle Royston is suited to investigating the case, but does not want to betray a colleague – and Royston’s own situation is not clear-cut, either…

For all the grim issues the novel confronts, they are balanced by touches of humour throughout the story. One of the threads running through the plot is Powell’s slowly unravelling marriage – a situation arising, it becomes clear, again out of the best of intentions; in one scene, he returns late from work yet again, and undresses next to his wife in the hope that there might be an amorous encounter. ‘ ‘Don’t roll your bloody socks into a ball.’ Her words were accompanied by the sound of her turning over, and the click of the light switch…Sex was certainly off.’

From the outset, Cutts creates a series of characters, none of whom has a clear-cut status that is morally right or wrong. The reader is left unsure where to place their sympathies, and is thereby drawn into the depths of a web of moral ambiguity. Each suspect – and some of the police, too – has a stain on their character, which only becomes clear as the novel unfolds, but each has some element of their background, some aspect to their story, that means a straight and outright condemnation by the reader is not possible. It’s an effective device that pulls the reader onwards, leading them through what might be called an ‘immorality play,’ a darkly intricate tale where, as one of the characters observes early in the novel, even though the case may be solved and justice brought, there can be no winners.

Mercy Killing is the first in Cutts’ East Rise Incident Room series, published by Simon and Schuster in 2016

Taking her heroine out of both her seaside town of Whitstable and her usual haunt of Canterbury, Wassmer instead opts to place her in an idyllic rural retreat near Chartham, setting the scene for that classic of the crime genre, the Country House Murder. It is a bold move, placing the book directly in the lineage of a British literay tradition reaching from Agatha Christie, Dorothy L Sayers and J Jefferson Farjeon to later luminaries such as PD James and Reginald Hill. This affords plenty of opportunities for vivid description of rural scenes and lakeside trysts which perfectly capture the lazy haze of an English countryside lulled by summer’s warmth, as well as giving Wassmer the opportunity to explore a more focused arena.

Taking her heroine out of both her seaside town of Whitstable and her usual haunt of Canterbury, Wassmer instead opts to place her in an idyllic rural retreat near Chartham, setting the scene for that classic of the crime genre, the Country House Murder. It is a bold move, placing the book directly in the lineage of a British literay tradition reaching from Agatha Christie, Dorothy L Sayers and J Jefferson Farjeon to later luminaries such as PD James and Reginald Hill. This affords plenty of opportunities for vivid description of rural scenes and lakeside trysts which perfectly capture the lazy haze of an English countryside lulled by summer’s warmth, as well as giving Wassmer the opportunity to explore a more focused arena.

Both women stressed the importance of research to their writing. Cutts attended an autopsy in order to inform part of one of her novels; she came away, she says, awed by the amount of work and commitment which goes in to them. “They’re not as clean and quick as they are on TV; they take hours!” she declared, whilst ruefully admitting to having worn the ‘wrong sort of shoes’ as she hadn’t anticipated standing for so long. For her Whitstable-based series featuring private detective-cum–restaurant-owner, Pearl Nolan, Wassmer spent last summer exploring locations including Reculver, Sheppey and Oare in order to widen the scope of her character’s travels. “Details are important,” Wassmer stated: “you don’t want a sackful of mail criticising a point in your book!” Although she balanced this by admitting that, for her, it is important to remember that, after all, it is the writer’s own world, one that they have created, and that on one level they can do what they like. Wassmer has had reviews where readers take issue with the geography of Whitstable as it appears in her books, with particular roads not leading to exactly the right road. Cutts says she often ends up shouting at television programmes; “No, no, no; you didn’t caution him!” before adding reflectively “it’s why I don’t really watch much crime drama on TV…”

Both women stressed the importance of research to their writing. Cutts attended an autopsy in order to inform part of one of her novels; she came away, she says, awed by the amount of work and commitment which goes in to them. “They’re not as clean and quick as they are on TV; they take hours!” she declared, whilst ruefully admitting to having worn the ‘wrong sort of shoes’ as she hadn’t anticipated standing for so long. For her Whitstable-based series featuring private detective-cum–restaurant-owner, Pearl Nolan, Wassmer spent last summer exploring locations including Reculver, Sheppey and Oare in order to widen the scope of her character’s travels. “Details are important,” Wassmer stated: “you don’t want a sackful of mail criticising a point in your book!” Although she balanced this by admitting that, for her, it is important to remember that, after all, it is the writer’s own world, one that they have created, and that on one level they can do what they like. Wassmer has had reviews where readers take issue with the geography of Whitstable as it appears in her books, with particular roads not leading to exactly the right road. Cutts says she often ends up shouting at television programmes; “No, no, no; you didn’t caution him!” before adding reflectively “it’s why I don’t really watch much crime drama on TV…” As usual, the novel is deeply rooted in its depiction of Whitstable itself, the book really a hymn to the town’s distinctive qualities; windswept beaches, boutique shops, a decorous high street, and wonderfully-titled alleyways. Forays into Canterbury are equally grounded in the real geography of the city, littered with streets and places which will be familiar to local readers (there’s quite a pleasurable feeling to be able to recognise places you know well in books, somehow…).

As usual, the novel is deeply rooted in its depiction of Whitstable itself, the book really a hymn to the town’s distinctive qualities; windswept beaches, boutique shops, a decorous high street, and wonderfully-titled alleyways. Forays into Canterbury are equally grounded in the real geography of the city, littered with streets and places which will be familiar to local readers (there’s quite a pleasurable feeling to be able to recognise places you know well in books, somehow…).

This happens to me quite often – as a compulsive book-buyer, this voice doesn’t need to shout any more, it just nudges me in the right direction and knows that I’ll comply, rolling its eyes (mixed metaphor, but you know what I mean) at the inevitability of it all – but not quite so compulsively as with

This happens to me quite often – as a compulsive book-buyer, this voice doesn’t need to shout any more, it just nudges me in the right direction and knows that I’ll comply, rolling its eyes (mixed metaphor, but you know what I mean) at the inevitability of it all – but not quite so compulsively as with

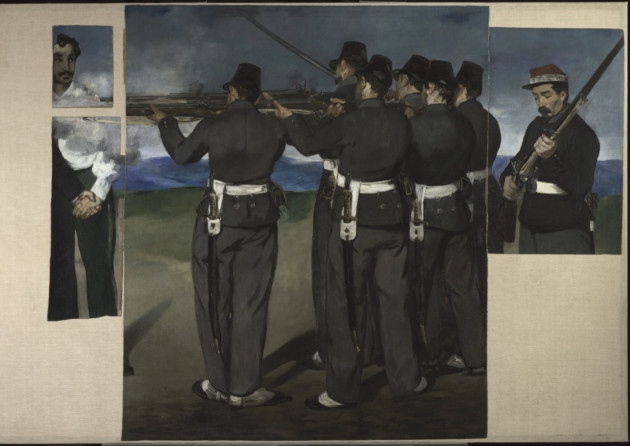

An earlier lithograph of the same scene renders the commonplace even more apparent, as Manet depicts a ragged bunch of street-urchins looking over the wall behind the scene, like everyday gawkers or the tricoteuse, those women who would sit and knit beside the guillotines.

An earlier lithograph of the same scene renders the commonplace even more apparent, as Manet depicts a ragged bunch of street-urchins looking over the wall behind the scene, like everyday gawkers or the tricoteuse, those women who would sit and knit beside the guillotines.

Science fiction and fantasy, traditionally viewed with grave suspicion by the supposedly more ‘serious’ of the mainstream fiction genres, have together been a flourishing literary canon for years; Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings regularly polls in high places as ‘Most Read,’ whilst writers like China Mieville, Alistair Reynolds and Peter F Hamilton have been patiently carving out successful careers with epic science fiction and fantasy novels for many years.

Science fiction and fantasy, traditionally viewed with grave suspicion by the supposedly more ‘serious’ of the mainstream fiction genres, have together been a flourishing literary canon for years; Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings regularly polls in high places as ‘Most Read,’ whilst writers like China Mieville, Alistair Reynolds and Peter F Hamilton have been patiently carving out successful careers with epic science fiction and fantasy novels for many years.