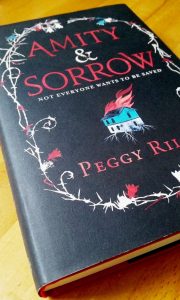

The first novel from Kent-based American author, Peggy Riley, Amity and Sorrow is a mesmerising exploration of the tension between the familiar and the unknown, of extremes of faith and the lengths to which people can be caught up in the fantasies of others.

The central figure, Amaranth, escapes with her two daughters from a cult, a fiercely isolated community led by her husband and his forty-nine other wives, and literally crashes into a world where they are confronted by an unfamiliar modernity. One daughter, Amity, embraces the flight, tentatively grasping the new-found opportunities offered by Bradley, the farmer who offers them refuge; the other, Sorrow, wants to return to her father, for reasons that slowly become clear as the book unfolds.

There are many good things about the novel, which is couched in a beautifully-wrought prose that seems to chime and dance with the same care for language manifest in Dylan Thomas’ Under Milk Wood or the novels of Joanne Harris. The beguiling triple-metre of the opening – ‘Amity watches what looks like the sun’ – typically sets the tone for the way it unfolds, part poem, part prose, part vision. Indeed, the prose so often treads the boundary of poetry that it’s easy to forget that it’s still a novel; ‘…to check that her daughters are safe in their blankets, all flung limbs and linen.’ Or the almost-musical cadences of ‘the white horse and red horse, the black horse and pale horse, the martyrs and saints and the stars crashing down.’

There are many good things about the novel, which is couched in a beautifully-wrought prose that seems to chime and dance with the same care for language manifest in Dylan Thomas’ Under Milk Wood or the novels of Joanne Harris. The beguiling triple-metre of the opening – ‘Amity watches what looks like the sun’ – typically sets the tone for the way it unfolds, part poem, part prose, part vision. Indeed, the prose so often treads the boundary of poetry that it’s easy to forget that it’s still a novel; ‘…to check that her daughters are safe in their blankets, all flung limbs and linen.’ Or the almost-musical cadences of ‘the white horse and red horse, the black horse and pale horse, the martyrs and saints and the stars crashing down.’

Sometimes, with its evocation of the arid dustscape of Oklahoma, the prose speaks in the voice of Joni Mitchell blowing in across the desert, a literary Hejira. ‘The land was hard and the people harder, but the sounds of the night were of sand switchbacking beneath snake-bellies, the cries of coyotes, the lonesome who-who-who of a horned owl from a Joshua tree.’ The atmosphere is painted in short, deft strokes that say much with little and hint at further darkness, with assonance, alliteration and rhythm all busily working together beneath the surface of the prose, yet in a way that never becomes intrusive.

At other times, it is not what’s said, but what is left missing that gives so much of the prose its gentle yet unbearable weight. ‘He hums his way into the kitchen with a tune she can almost remember, from long ago, something about love and dancing.’

Riley never lets the reader forget about the essential human fable unfolding against the scenery, though. The way the focus pulls from a panoramic sweep across dusty crop-fields to reflections framed in a window makes the reader aware, all the time, of context, of the human saga unfolding against the wider landscape. ‘Let us remember that every child can change the world,’ a glimpse of a Universal Truth beneath the horror.

Riley never lets the reader forget about the essential human fable unfolding against the scenery, though. The way the focus pulls from a panoramic sweep across dusty crop-fields to reflections framed in a window makes the reader aware, all the time, of context, of the human saga unfolding against the wider landscape. ‘Let us remember that every child can change the world,’ a glimpse of a Universal Truth beneath the horror.

At one point, the book becomes delightfully Hitchcockian. ‘Amaranth carries a bowl of plain cooked rice up the stairs. She does not know what she will find behind the locked door. She can almost picture Bradley’s wife there, imprisoned for threatening to leave, now deranged and knocking, wasting away.’

At one point, the book becomes delightfully Hitchcockian. ‘Amaranth carries a bowl of plain cooked rice up the stairs. She does not know what she will find behind the locked door. She can almost picture Bradley’s wife there, imprisoned for threatening to leave, now deranged and knocking, wasting away.’

For all the bleakness, there are occasional moments of real humour, which provide wonderful moments of contrast.

“Ain’t you hot with that thing on your head? It’s makin’ me hot.”

She leans on the threshold. “It’s for Saint Paul.”

“Patron saint of hats? ”

Elsewhere, passages dip and lilt with the half-memory of nursery-rhyme: ‘She isn’t in the bathroom, isn’t splashing at the sink. She runs past the pump to the red dirt road but there is no Sorrow, no dust cloud of her running.’ And some passages hiss with sibilance, pop with consonants: ‘Her clogs totter over furrows between bristle-topped grasses, yellowing, crisp and whispery on her skirts as she brushes past.’

The further the reader is drawn into the book, the more it becomes less a novel than an extended incantation. Often, a real sense of menace hovers above the rhythmic step of the prose:

The further the reader is drawn into the book, the more it becomes less a novel than an extended incantation. Often, a real sense of menace hovers above the rhythmic step of the prose:

‘Amaranth holds a paring knife, bone-handled and sharp from a kitchen drawer.’…

a sensation which Riley draws out over much of the book; in fact, it takes just over three hundred pages for the latent menace which hangs over the novel to manifest itself – and when it does, the effect is utterly terrifying.

At the novel’s conclusion, the reader is left somehow with the sense that this has been a darker Wizard of Oz; sepia-tinged grasslands, the Red Dirt Road instead of the Yellow Brick one leading to a more menacing place than the Emerald City, although ultmately there is hope. It is a riveting tale, woven in a way that dances and spins across the page, part-prose, part-poetry, hovering like a nursery-rhyme, panoramic in scope and delivered almost cinematically but with the fragility of fraught human relationships at its heart. Riley fords the Red Dirt Road; readers who follow are in for a memorable experience.

Amity and Sorrow was published by Tinder Press in 2013.

What Cutts is exploring in the novel, a gritty, urban police procedural informed by her own experiences as an investigating detective, is the idea that bad things can come from good intentions, a concept which affects all the characters involved in the drama, and which sees each of them grappling with their own conflicts and making uncomfortable liaisons. At the head of the case, DI Powell is fully aware that, to solve the case, he must ‘break bread with a monster,’ and knows precisely the moment when he crosses the line. His personal dance with the devil involves a meeting with the less than wholesome Martha, who leads the Volunteer Army, a group of local people which at first seems to have a positive mandate – those involved are ‘trying to make it as safe for people as they can about living with sex offenders around them and we want to work with the police. We’re trying to do our bit to help.’ Yet urban vigilantes taking the law into their own hands is never a good idea, and later in the book the reason for the creation of the group is revealed, arising as it does from yet another evil beginning.

What Cutts is exploring in the novel, a gritty, urban police procedural informed by her own experiences as an investigating detective, is the idea that bad things can come from good intentions, a concept which affects all the characters involved in the drama, and which sees each of them grappling with their own conflicts and making uncomfortable liaisons. At the head of the case, DI Powell is fully aware that, to solve the case, he must ‘break bread with a monster,’ and knows precisely the moment when he crosses the line. His personal dance with the devil involves a meeting with the less than wholesome Martha, who leads the Volunteer Army, a group of local people which at first seems to have a positive mandate – those involved are ‘trying to make it as safe for people as they can about living with sex offenders around them and we want to work with the police. We’re trying to do our bit to help.’ Yet urban vigilantes taking the law into their own hands is never a good idea, and later in the book the reason for the creation of the group is revealed, arising as it does from yet another evil beginning.

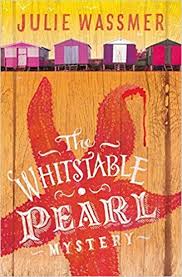

Taking her heroine out of both her seaside town of Whitstable and her usual haunt of Canterbury, Wassmer instead opts to place her in an idyllic rural retreat near Chartham, setting the scene for that classic of the crime genre, the Country House Murder. It is a bold move, placing the book directly in the lineage of a British literay tradition reaching from Agatha Christie, Dorothy L Sayers and J Jefferson Farjeon to later luminaries such as PD James and Reginald Hill. This affords plenty of opportunities for vivid description of rural scenes and lakeside trysts which perfectly capture the lazy haze of an English countryside lulled by summer’s warmth, as well as giving Wassmer the opportunity to explore a more focused arena.

Taking her heroine out of both her seaside town of Whitstable and her usual haunt of Canterbury, Wassmer instead opts to place her in an idyllic rural retreat near Chartham, setting the scene for that classic of the crime genre, the Country House Murder. It is a bold move, placing the book directly in the lineage of a British literay tradition reaching from Agatha Christie, Dorothy L Sayers and J Jefferson Farjeon to later luminaries such as PD James and Reginald Hill. This affords plenty of opportunities for vivid description of rural scenes and lakeside trysts which perfectly capture the lazy haze of an English countryside lulled by summer’s warmth, as well as giving Wassmer the opportunity to explore a more focused arena.

Both women stressed the importance of research to their writing. Cutts attended an autopsy in order to inform part of one of her novels; she came away, she says, awed by the amount of work and commitment which goes in to them. “They’re not as clean and quick as they are on TV; they take hours!” she declared, whilst ruefully admitting to having worn the ‘wrong sort of shoes’ as she hadn’t anticipated standing for so long. For her Whitstable-based series featuring private detective-cum–restaurant-owner, Pearl Nolan, Wassmer spent last summer exploring locations including Reculver, Sheppey and Oare in order to widen the scope of her character’s travels. “Details are important,” Wassmer stated: “you don’t want a sackful of mail criticising a point in your book!” Although she balanced this by admitting that, for her, it is important to remember that, after all, it is the writer’s own world, one that they have created, and that on one level they can do what they like. Wassmer has had reviews where readers take issue with the geography of Whitstable as it appears in her books, with particular roads not leading to exactly the right road. Cutts says she often ends up shouting at television programmes; “No, no, no; you didn’t caution him!” before adding reflectively “it’s why I don’t really watch much crime drama on TV…”

Both women stressed the importance of research to their writing. Cutts attended an autopsy in order to inform part of one of her novels; she came away, she says, awed by the amount of work and commitment which goes in to them. “They’re not as clean and quick as they are on TV; they take hours!” she declared, whilst ruefully admitting to having worn the ‘wrong sort of shoes’ as she hadn’t anticipated standing for so long. For her Whitstable-based series featuring private detective-cum–restaurant-owner, Pearl Nolan, Wassmer spent last summer exploring locations including Reculver, Sheppey and Oare in order to widen the scope of her character’s travels. “Details are important,” Wassmer stated: “you don’t want a sackful of mail criticising a point in your book!” Although she balanced this by admitting that, for her, it is important to remember that, after all, it is the writer’s own world, one that they have created, and that on one level they can do what they like. Wassmer has had reviews where readers take issue with the geography of Whitstable as it appears in her books, with particular roads not leading to exactly the right road. Cutts says she often ends up shouting at television programmes; “No, no, no; you didn’t caution him!” before adding reflectively “it’s why I don’t really watch much crime drama on TV…”