The first novel from Kent-based American author, Peggy Riley, Amity and Sorrow is a mesmerising exploration of the tension between the familiar and the unknown, of extremes of faith and the lengths to which people can be caught up in the fantasies of others.

The central figure, Amaranth, escapes with her two daughters from a cult, a fiercely isolated community led by her husband and his forty-nine other wives, and literally crashes into a world where they are confronted by an unfamiliar modernity. One daughter, Amity, embraces the flight, tentatively grasping the new-found opportunities offered by Bradley, the farmer who offers them refuge; the other, Sorrow, wants to return to her father, for reasons that slowly become clear as the book unfolds.

There are many good things about the novel, which is couched in a beautifully-wrought prose that seems to chime and dance with the same care for language manifest in Dylan Thomas’ Under Milk Wood or the novels of Joanne Harris. The beguiling triple-metre of the opening – ‘Amity watches what looks like the sun’ – typically sets the tone for the way it unfolds, part poem, part prose, part vision. Indeed, the prose so often treads the boundary of poetry that it’s easy to forget that it’s still a novel; ‘…to check that her daughters are safe in their blankets, all flung limbs and linen.’ Or the almost-musical cadences of ‘the white horse and red horse, the black horse and pale horse, the martyrs and saints and the stars crashing down.’

There are many good things about the novel, which is couched in a beautifully-wrought prose that seems to chime and dance with the same care for language manifest in Dylan Thomas’ Under Milk Wood or the novels of Joanne Harris. The beguiling triple-metre of the opening – ‘Amity watches what looks like the sun’ – typically sets the tone for the way it unfolds, part poem, part prose, part vision. Indeed, the prose so often treads the boundary of poetry that it’s easy to forget that it’s still a novel; ‘…to check that her daughters are safe in their blankets, all flung limbs and linen.’ Or the almost-musical cadences of ‘the white horse and red horse, the black horse and pale horse, the martyrs and saints and the stars crashing down.’

Sometimes, with its evocation of the arid dustscape of Oklahoma, the prose speaks in the voice of Joni Mitchell blowing in across the desert, a literary Hejira. ‘The land was hard and the people harder, but the sounds of the night were of sand switchbacking beneath snake-bellies, the cries of coyotes, the lonesome who-who-who of a horned owl from a Joshua tree.’ The atmosphere is painted in short, deft strokes that say much with little and hint at further darkness, with assonance, alliteration and rhythm all busily working together beneath the surface of the prose, yet in a way that never becomes intrusive.

At other times, it is not what’s said, but what is left missing that gives so much of the prose its gentle yet unbearable weight. ‘He hums his way into the kitchen with a tune she can almost remember, from long ago, something about love and dancing.’

Riley never lets the reader forget about the essential human fable unfolding against the scenery, though. The way the focus pulls from a panoramic sweep across dusty crop-fields to reflections framed in a window makes the reader aware, all the time, of context, of the human saga unfolding against the wider landscape. ‘Let us remember that every child can change the world,’ a glimpse of a Universal Truth beneath the horror.

Riley never lets the reader forget about the essential human fable unfolding against the scenery, though. The way the focus pulls from a panoramic sweep across dusty crop-fields to reflections framed in a window makes the reader aware, all the time, of context, of the human saga unfolding against the wider landscape. ‘Let us remember that every child can change the world,’ a glimpse of a Universal Truth beneath the horror.

At one point, the book becomes delightfully Hitchcockian. ‘Amaranth carries a bowl of plain cooked rice up the stairs. She does not know what she will find behind the locked door. She can almost picture Bradley’s wife there, imprisoned for threatening to leave, now deranged and knocking, wasting away.’

At one point, the book becomes delightfully Hitchcockian. ‘Amaranth carries a bowl of plain cooked rice up the stairs. She does not know what she will find behind the locked door. She can almost picture Bradley’s wife there, imprisoned for threatening to leave, now deranged and knocking, wasting away.’

For all the bleakness, there are occasional moments of real humour, which provide wonderful moments of contrast.

“Ain’t you hot with that thing on your head? It’s makin’ me hot.”

She leans on the threshold. “It’s for Saint Paul.”

“Patron saint of hats? ”

Elsewhere, passages dip and lilt with the half-memory of nursery-rhyme: ‘She isn’t in the bathroom, isn’t splashing at the sink. She runs past the pump to the red dirt road but there is no Sorrow, no dust cloud of her running.’ And some passages hiss with sibilance, pop with consonants: ‘Her clogs totter over furrows between bristle-topped grasses, yellowing, crisp and whispery on her skirts as she brushes past.’

The further the reader is drawn into the book, the more it becomes less a novel than an extended incantation. Often, a real sense of menace hovers above the rhythmic step of the prose:

The further the reader is drawn into the book, the more it becomes less a novel than an extended incantation. Often, a real sense of menace hovers above the rhythmic step of the prose:

‘Amaranth holds a paring knife, bone-handled and sharp from a kitchen drawer.’…

a sensation which Riley draws out over much of the book; in fact, it takes just over three hundred pages for the latent menace which hangs over the novel to manifest itself – and when it does, the effect is utterly terrifying.

At the novel’s conclusion, the reader is left somehow with the sense that this has been a darker Wizard of Oz; sepia-tinged grasslands, the Red Dirt Road instead of the Yellow Brick one leading to a more menacing place than the Emerald City, although ultmately there is hope. It is a riveting tale, woven in a way that dances and spins across the page, part-prose, part-poetry, hovering like a nursery-rhyme, panoramic in scope and delivered almost cinematically but with the fragility of fraught human relationships at its heart. Riley fords the Red Dirt Road; readers who follow are in for a memorable experience.

Amity and Sorrow was published by Tinder Press in 2013.

Her debut EP, Lockdown Loser, reflecting on life (and released) during the pandemic, opens with that weighty injunction from Boris which issued forth from our television screens, “You must stay at home,” and lamenting sax leads into her trademark, clear-sighted, torchbeam of self-scrutiny. couldn’t play it cool sashays in with a summery smile, and the comfortable shuffle of you can’t come and stay charts a relationship’s slow decline with remarkably good cheer. There’s a lovely Sunday-morning-relaxed vibe to coffee in our underwear, and the album closes with the cheerful melancholia that’s an appealing feature of her music as a whole.

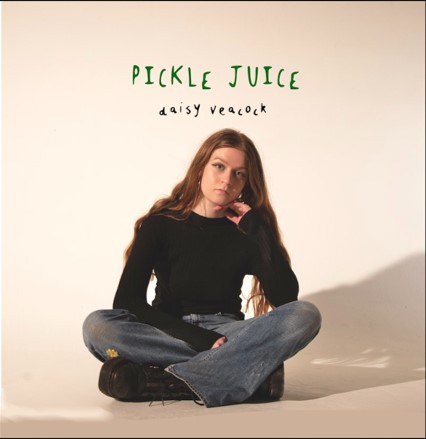

Her debut EP, Lockdown Loser, reflecting on life (and released) during the pandemic, opens with that weighty injunction from Boris which issued forth from our television screens, “You must stay at home,” and lamenting sax leads into her trademark, clear-sighted, torchbeam of self-scrutiny. couldn’t play it cool sashays in with a summery smile, and the comfortable shuffle of you can’t come and stay charts a relationship’s slow decline with remarkably good cheer. There’s a lovely Sunday-morning-relaxed vibe to coffee in our underwear, and the album closes with the cheerful melancholia that’s an appealing feature of her music as a whole. Still in her early twenties, there’s already an assuredness and deft musicality to her writing; her latest offering, due for release on 5th August, Pickle Juice, puns on the sonic similarity of ‘pick or choose / pickle juice’ and keeps in the same charming vein – here’s hoping her persistent efforts to persuade the Branston company to adopt it as their signature melody pays off. It would be a moment to relish…

Still in her early twenties, there’s already an assuredness and deft musicality to her writing; her latest offering, due for release on 5th August, Pickle Juice, puns on the sonic similarity of ‘pick or choose / pickle juice’ and keeps in the same charming vein – here’s hoping her persistent efforts to persuade the Branston company to adopt it as their signature melody pays off. It would be a moment to relish…

‘Plays Well With Others’ is, of course, how one might enthuse about a new child finding its feet on entering a new school, and it’s an apt title for loadbang’s latest release, a series of challenging and often playful contemporary works celebrating unusual works for an unusual line-up.

‘Plays Well With Others’ is, of course, how one might enthuse about a new child finding its feet on entering a new school, and it’s an apt title for loadbang’s latest release, a series of challenging and often playful contemporary works celebrating unusual works for an unusual line-up.

From Riveting Reads to Top TV, Lockdown Listening and Winning Watches, the feature will create a sort of cultural oasis, with hopefully something here for everyone. We’ll be sharing one of each as the feature appears (with links), with the hope that there will be something to amuse, occupy, and keep you company during the coming months.

From Riveting Reads to Top TV, Lockdown Listening and Winning Watches, the feature will create a sort of cultural oasis, with hopefully something here for everyone. We’ll be sharing one of each as the feature appears (with links), with the hope that there will be something to amuse, occupy, and keep you company during the coming months. It’s also about the tension between the older generation and the young; whilst Pearl is efficiently navigating her smartphone to read the latest revelations about the case, or texting DCI McGuire (with whom she shares both the investigation as well as her heart), it’s her mother, Dolly, who resorts to picking up and reading an actual newspaper. Although the novel relies on the traditional murder and investigation as its narrative outline, the driving force is its head-on look at media power – the influence it wields, its ability to sway minds, and the lengths people will go to in order to create and control headlines.

It’s also about the tension between the older generation and the young; whilst Pearl is efficiently navigating her smartphone to read the latest revelations about the case, or texting DCI McGuire (with whom she shares both the investigation as well as her heart), it’s her mother, Dolly, who resorts to picking up and reading an actual newspaper. Although the novel relies on the traditional murder and investigation as its narrative outline, the driving force is its head-on look at media power – the influence it wields, its ability to sway minds, and the lengths people will go to in order to create and control headlines. Wassmer controls the pace and set-pieces of the drama well; the set-piece of the medieval pageant atop the downs has a nice cinematic feel, leading into the lighting of the beacon to symbolise the protest’s public beginning. There’s a Gothic denouement atop the Black Mill (a genuine former working mill that stands at the top of Borstal Hill – location and geographical accuracy remains a constant throughout the series, and is a major aspect of the appeal of the books both for local reader as well as aspiring literary visitors), complete with flashes of lightning and ominous thunder. And the Black Mill is again a significant emblem of the old-versus-new dynamic – standing in the mill, Pearl is afforded a view of the estuary, in whose waters stands the modern wind-farm, its red lights glowing in the darkness. There are also some gently comic touches; a moment of, if not coitus interruptus, then coitus notquitestartedus in a secluded meadow, and a nicely tart dig at a paper’s presumption of impartiality:

Wassmer controls the pace and set-pieces of the drama well; the set-piece of the medieval pageant atop the downs has a nice cinematic feel, leading into the lighting of the beacon to symbolise the protest’s public beginning. There’s a Gothic denouement atop the Black Mill (a genuine former working mill that stands at the top of Borstal Hill – location and geographical accuracy remains a constant throughout the series, and is a major aspect of the appeal of the books both for local reader as well as aspiring literary visitors), complete with flashes of lightning and ominous thunder. And the Black Mill is again a significant emblem of the old-versus-new dynamic – standing in the mill, Pearl is afforded a view of the estuary, in whose waters stands the modern wind-farm, its red lights glowing in the darkness. There are also some gently comic touches; a moment of, if not coitus interruptus, then coitus notquitestartedus in a secluded meadow, and a nicely tart dig at a paper’s presumption of impartiality: There are many good things about the novel, which is couched in a beautifully-wrought prose that seems to chime and dance with the same care for language manifest in Dylan Thomas’ Under Milk Wood or the novels of Joanne Harris. The beguiling triple-metre of the opening – ‘Amity watches what looks like the sun’ – typically sets the tone for the way it unfolds, part poem, part prose, part vision. Indeed, the prose so often treads the boundary of poetry that it’s easy to forget that it’s still a novel; ‘…to check that her daughters are safe in their blankets, all flung limbs and linen.’ Or the almost-musical cadences of ‘the white horse and red horse, the black horse and pale horse, the martyrs and saints and the stars crashing down.’

There are many good things about the novel, which is couched in a beautifully-wrought prose that seems to chime and dance with the same care for language manifest in Dylan Thomas’ Under Milk Wood or the novels of Joanne Harris. The beguiling triple-metre of the opening – ‘Amity watches what looks like the sun’ – typically sets the tone for the way it unfolds, part poem, part prose, part vision. Indeed, the prose so often treads the boundary of poetry that it’s easy to forget that it’s still a novel; ‘…to check that her daughters are safe in their blankets, all flung limbs and linen.’ Or the almost-musical cadences of ‘the white horse and red horse, the black horse and pale horse, the martyrs and saints and the stars crashing down.’ Riley never lets the reader forget about the essential human fable unfolding against the scenery, though. The way the focus pulls from a panoramic sweep across dusty crop-fields to reflections framed in a window makes the reader aware, all the time, of context, of the human saga unfolding against the wider landscape. ‘Let us remember that every child can change the world,’ a glimpse of a Universal Truth beneath the horror.

Riley never lets the reader forget about the essential human fable unfolding against the scenery, though. The way the focus pulls from a panoramic sweep across dusty crop-fields to reflections framed in a window makes the reader aware, all the time, of context, of the human saga unfolding against the wider landscape. ‘Let us remember that every child can change the world,’ a glimpse of a Universal Truth beneath the horror. At one point, the book becomes delightfully Hitchcockian. ‘Amaranth carries a bowl of plain cooked rice up the stairs. She does not know what she will find behind the locked door. She can almost picture Bradley’s wife there, imprisoned for threatening to leave, now deranged and knocking, wasting away.’

At one point, the book becomes delightfully Hitchcockian. ‘Amaranth carries a bowl of plain cooked rice up the stairs. She does not know what she will find behind the locked door. She can almost picture Bradley’s wife there, imprisoned for threatening to leave, now deranged and knocking, wasting away.’ The further the reader is drawn into the book, the more it becomes less a novel than an extended incantation. Often, a real sense of menace hovers above the rhythmic step of the prose:

The further the reader is drawn into the book, the more it becomes less a novel than an extended incantation. Often, a real sense of menace hovers above the rhythmic step of the prose: