Our discussion about the film included: consideration of its melodramatic elements; its relation to Charles Dickens and other film adaptations of Dickens’ novels; its placing in Dirk Bogarde’s filmography and screen and star images.

It was noted that a certain suspension of belief was necessary when faced with the twists, turns and coincidences of the plot as well as the suffering, sacrifice, hidden secrets and lost memories of the characters. The film opens with the carriage in which banker Jarvis Lorry (Cecil Parker), lawyer Sydney Carton and Basard (Donald Pleasance) being stopped dramatically. This is not the high-jacking the occupants and the audience initially fear, and instead the enigmatic message ‘recalled to life’ is delivered to Lorry. We discover that this relates to the news that Frenchman Doctor Alexandre Manette (Stephen Murray) has been rediscovered, after spending 18 years in the French Bastille prison.  The reunion of Doctor Manette with his daughter Lucie (Dorothy Tutin) is prefigured by her expressing extreme emotion and this is furthered when the pair meets since it is clear that her father has lost his memory as well as his wits. With Lucie’s help, Doctor Manette is soon on the road to recovery, but the entrance of two men into the story – attractive Frenchman Charles Darnay (Paul Guers) and handsome English lawyer Sydney Carton (Dirk Bogarde) soon complicates Lucie’s life.

The reunion of Doctor Manette with his daughter Lucie (Dorothy Tutin) is prefigured by her expressing extreme emotion and this is furthered when the pair meets since it is clear that her father has lost his memory as well as his wits. With Lucie’s help, Doctor Manette is soon on the road to recovery, but the entrance of two men into the story – attractive Frenchman Charles Darnay (Paul Guers) and handsome English lawyer Sydney Carton (Dirk Bogarde) soon complicates Lucie’s life.  After Lucie briefly mistakes Carton for Darnay, the former, now of course in love with Lucie, soon coincidentally helps to represent his love rival in an English court. Darnay is facing trumped up charges of treason which have been instigated by his cousin the Marquis St Evremonde (Christopher Lee) and Basard. Carton succeeds in achieving Darnay’s acquittal by pointing out his own and Darnay’s resemblance to one another in order to undermine a witness’ testimony.

After Lucie briefly mistakes Carton for Darnay, the former, now of course in love with Lucie, soon coincidentally helps to represent his love rival in an English court. Darnay is facing trumped up charges of treason which have been instigated by his cousin the Marquis St Evremonde (Christopher Lee) and Basard. Carton succeeds in achieving Darnay’s acquittal by pointing out his own and Darnay’s resemblance to one another in order to undermine a witness’ testimony.

The situation in Paris is also eventful. The Marquis St Evremonde stands in for the entire aristocracy who are so despised by the ‘common’ French people. His family has previously traumatised Madame Defarge (Rosalie Crutchley), the wife of Manette’s servant (Duncan Lamont), by killing her siblings and parents. The Marquis St Evremonde continues this awful behaviour by sexually abusing his female servants and callously dismissing the peasant Gaspard’s grief as his young son is killed under the wheels of St Evremonde’s carriage. Gaspard exacts his revenge by stabbing the cruel aristocrat to death, and the French revolution is soon fully in flow and the and the Bastille violently breached.

The situation in Paris is also eventful. The Marquis St Evremonde stands in for the entire aristocracy who are so despised by the ‘common’ French people. His family has previously traumatised Madame Defarge (Rosalie Crutchley), the wife of Manette’s servant (Duncan Lamont), by killing her siblings and parents. The Marquis St Evremonde continues this awful behaviour by sexually abusing his female servants and callously dismissing the peasant Gaspard’s grief as his young son is killed under the wheels of St Evremonde’s carriage. Gaspard exacts his revenge by stabbing the cruel aristocrat to death, and the French revolution is soon fully in flow and the and the Bastille violently breached.

Following the Marquis St Evremonde’s death Darnay (now married to Lucie, though keeping his family identity secret) travels to Paris, only to be caught up in the anti-aristocratic feeling. He is put on trial again, this time as an enemy of the French people. Tense scenes see him acquitted after Lucie, her father, and Carton travel to Paris to speak on his behalf. This is then overturned by the understandably vengeful Madame Defarge denouncing Darnay with evidence found in Manette’s old cell. Darnay is sentenced to the guillotine and the now-pregnant Lucie faces danger as the baby she is carrying means continuation of the despised St Evremonde line. Carton steps in when he recognises the Marquis St Evremonde’s former partner-in-crime Basard who is now a jailer at the Bastille. (Basard has, somewhat incredibly, earlier escaped justice in England by faking his own death.) The doubling of Carton and Darnay which has first been seen in Lucie’s misidentification and put to use by Carton in defending Darnay in court comes to the fore once more. Carton arrives at the Bastille, apparently drunk, to visit Darnay. He overpowers Darnay and takes his place, having persuaded Basard to accompany the now insensible Darnay out of the building into the care of Darnay’s wife, father-in-law and Lucie’s faithful companion the elderly Miss Pross (Athene Seyler). The seemingly drunken Darnay is mistaken for Carton as he

Following the Marquis St Evremonde’s death Darnay (now married to Lucie, though keeping his family identity secret) travels to Paris, only to be caught up in the anti-aristocratic feeling. He is put on trial again, this time as an enemy of the French people. Tense scenes see him acquitted after Lucie, her father, and Carton travel to Paris to speak on his behalf. This is then overturned by the understandably vengeful Madame Defarge denouncing Darnay with evidence found in Manette’s old cell. Darnay is sentenced to the guillotine and the now-pregnant Lucie faces danger as the baby she is carrying means continuation of the despised St Evremonde line. Carton steps in when he recognises the Marquis St Evremonde’s former partner-in-crime Basard who is now a jailer at the Bastille. (Basard has, somewhat incredibly, earlier escaped justice in England by faking his own death.) The doubling of Carton and Darnay which has first been seen in Lucie’s misidentification and put to use by Carton in defending Darnay in court comes to the fore once more. Carton arrives at the Bastille, apparently drunk, to visit Darnay. He overpowers Darnay and takes his place, having persuaded Basard to accompany the now insensible Darnay out of the building into the care of Darnay’s wife, father-in-law and Lucie’s faithful companion the elderly Miss Pross (Athene Seyler). The seemingly drunken Darnay is mistaken for Carton as he  travels with his family to the check-point, since Carton had previously discussed his own love of French wine with the guards on his journey into the country. Finally, in perhaps the most famous instance of self-sacrifice in English literature, Carton takes Darnay’s place at the guillotine.

travels with his family to the check-point, since Carton had previously discussed his own love of French wine with the guards on his journey into the country. Finally, in perhaps the most famous instance of self-sacrifice in English literature, Carton takes Darnay’s place at the guillotine.

Perhaps surprisingly, given the amount of plot to rattle though and the revelations of various characters to be uncovered, there is a notable variety of rhythm in the film. Generally, the more staid and slower scenes are set in London, with those in Paris more rapidly paced. Time is also found for Dickensian comic relief provided by the lower-class English characters, especially Miss Pross and Jerry Cruncher (Alfie Bass). We also noted a hierarchy since the lower-class English characters are in the main depicted as better than the lower-class French characters. This is most obviously expressed when proud Briton Miss Pross (in her first, and she hopes only, visit abroad) is pitched against embittered French revolutionary Madame Defarge: Miss Pross is victorious.

Despite the fact that the French are portrayed as unnecessarily vengeful, we commented on similarities to some scenes from Russian director Sergei Eisenstein’s films which celebrated that county’s revolution. The relation of this to rhythm of A Tale of Two Cities’ editing was noted, especially its occasional use of montage (with the drumming revolutionaries centre stage) as well as its employment of unexpected camera angles. We also remarked upon the symbolism of peacocks. These birds are seen strutting around on St Evremonde’s lawn to demonstrate the Marquis’ arrogance and sense of entitlement. This brought to mind the way revolutionary leader Alexander Kerensky’s importance was punctured by comparing him to a mechanical version of the bird in in Eisenstein’s October: Ten Days That Shook the World (1927). Interestingly, the film was apparently popular with Russian audiences according to its director Ralph Thomas (Brian McFarlane, An Autobiography of British Cinema, 1997, p. 559). He attributed this to the non-commercial decision to film in black and white rather than colour, though it is also perhaps helped by the revolutionary subject matter, notwithstanding its negative portrayal of those involved.

Despite the fact that the French are portrayed as unnecessarily vengeful, we commented on similarities to some scenes from Russian director Sergei Eisenstein’s films which celebrated that county’s revolution. The relation of this to rhythm of A Tale of Two Cities’ editing was noted, especially its occasional use of montage (with the drumming revolutionaries centre stage) as well as its employment of unexpected camera angles. We also remarked upon the symbolism of peacocks. These birds are seen strutting around on St Evremonde’s lawn to demonstrate the Marquis’ arrogance and sense of entitlement. This brought to mind the way revolutionary leader Alexander Kerensky’s importance was punctured by comparing him to a mechanical version of the bird in in Eisenstein’s October: Ten Days That Shook the World (1927). Interestingly, the film was apparently popular with Russian audiences according to its director Ralph Thomas (Brian McFarlane, An Autobiography of British Cinema, 1997, p. 559). He attributed this to the non-commercial decision to film in black and white rather than colour, though it is also perhaps helped by the revolutionary subject matter, notwithstanding its negative portrayal of those involved.

The film interestingly does not open with the novel’s famous narration ‘it was the best of times, it was the worst of times…’ but dives straight into the action of the possibly hijacked coach. Unlike other British films of Dickens’ work – such as Henry Edwards’ Scrooge (1935) and David Lean’s Great Expectations (1946) and Oliver Twist (1948) – A Tale of Two Cities (1958) does not start with a shot of the novel. It consequently pushes Dickens somewhat into the background. This is especially noticeable when it is compared to Jack Conway’s 1935 Hollywood interpretation A Tale of Two Cities starring Ronald Colman. This not only starts with the page of the book pictured on screen but voices the famous opening lines. Perhaps then, the 1958 film points to changes in whether, and how, films claimed fidelity to their source texts.

The film interestingly does not open with the novel’s famous narration ‘it was the best of times, it was the worst of times…’ but dives straight into the action of the possibly hijacked coach. Unlike other British films of Dickens’ work – such as Henry Edwards’ Scrooge (1935) and David Lean’s Great Expectations (1946) and Oliver Twist (1948) – A Tale of Two Cities (1958) does not start with a shot of the novel. It consequently pushes Dickens somewhat into the background. This is especially noticeable when it is compared to Jack Conway’s 1935 Hollywood interpretation A Tale of Two Cities starring Ronald Colman. This not only starts with the page of the book pictured on screen but voices the famous opening lines. Perhaps then, the 1958 film points to changes in whether, and how, films claimed fidelity to their source texts.

The adding of Carton to the opening of the 1958 adaptation strains credibility in terms of coincidence but allows star Bogarde to appear earlier in the narrative. The film also diverges from Dickens’ novel with a rather disjunctive flashback as Lorry explains to Lucie her father’s history. Scenes depicting members of St Evremonde’s family abusing those of the lower classes explains the motivations of those rising up against the aristocracy, especially Madame Defarge. For much of the film some of us even forgot that we were watching a Dickens adaptation, our memories only being jolted by Dickens’ characteristic inclusion of unusual names – such as Mr Cruncher. Like Dickens’ Barnaby Rudge (1841) (set in England during the religious Gordon riots of 1780) A Tale of Two Cities is an historical novel. The society being criticised is therefore not the one that was contemporaneous to Dickens. This shows onscreen as the film’s events and costumes set it decades ahead of most of his works. While the Bogarde version distances itself from Dickens by not including the famous opening lines, changing when Carton enters the narrative and inserting a flashback early on, it does include the novel’s famous closing lines. We found the ending when Bogarde voices Carton’s thoughts ‘it is a far, far better thing I do , than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known’ profoundly moving. This was aided by Bogarde’s performance and his interaction with Marie Gabelle (Marie Versini) erstwhile maid of the St Evremondes who realises the sacrifice Carton is making, and with whom he shares his final moments.

, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known’ profoundly moving. This was aided by Bogarde’s performance and his interaction with Marie Gabelle (Marie Versini) erstwhile maid of the St Evremondes who realises the sacrifice Carton is making, and with whom he shares his final moments.

Since the film does diverge from Dickens it is helpful to briefly consider the writer who adapted it for the screen. T.E.B. Clarke was a writer better known for his Ealing comedies including Passport to Pimlico (1949) and The Lavender Hill Mob (1951). He also wrote dramas, notably The Blue Lamp (1950) – a semi documentary style film in which Bogarde starred as a young villain. While initially his comedy background makes Clarke seem an unusual choice, he was nonetheless connected to Bogarde. Indeed, Bogarde later praised Clarke’s adaption of Dickens’ novel as ‘excellent’ and capturing the ‘essence’ of Dickens’ original (McFarlane, 1997, p. 69), though production designer Carmen Dillon was less complementary, describing it as not being Clarke’s ‘cup of tea’ (p. 178).

Since the film does diverge from Dickens it is helpful to briefly consider the writer who adapted it for the screen. T.E.B. Clarke was a writer better known for his Ealing comedies including Passport to Pimlico (1949) and The Lavender Hill Mob (1951). He also wrote dramas, notably The Blue Lamp (1950) – a semi documentary style film in which Bogarde starred as a young villain. While initially his comedy background makes Clarke seem an unusual choice, he was nonetheless connected to Bogarde. Indeed, Bogarde later praised Clarke’s adaption of Dickens’ novel as ‘excellent’ and capturing the ‘essence’ of Dickens’ original (McFarlane, 1997, p. 69), though production designer Carmen Dillon was less complementary, describing it as not being Clarke’s ‘cup of tea’ (p. 178).

It is useful to comment on where A Tale of Two Cities sits in Bogarde’s filmography. It was released three years after the last Bogarde film we screened, Cast a Dark Shadow (1955), in which he played a wife killer with no redeeming features. In A Tale of Two Cities, Bogarde’s Carton is to start with a little unsympathetic, though his drunkenness is self-destructive rather than harmful to others, and he has charm despite his occasional moroseness. Carton finds purpose by sacrificing himself for the woman he loves, and this in turn saves him.

It is useful to comment on where A Tale of Two Cities sits in Bogarde’s filmography. It was released three years after the last Bogarde film we screened, Cast a Dark Shadow (1955), in which he played a wife killer with no redeeming features. In A Tale of Two Cities, Bogarde’s Carton is to start with a little unsympathetic, though his drunkenness is self-destructive rather than harmful to others, and he has charm despite his occasional moroseness. Carton finds purpose by sacrificing himself for the woman he loves, and this in turn saves him.

These two sides of Carton’s character are not as divergent as some of Bogarde’s earlier roles in films we have screened – most notably in Esther Waters (1948) and Hunted (1952). But it contrasts to the less complex roles Bogarde played after Cast a Dark Shadow – The Spanish Gardener (1956), Ill Met by Moonlight (1957), Campbell’s Kingdom (1957) and, most significantly, the third in the popular series of Doctor films: Doctor at Large (1957). The films in this series were helmed by A Tale of Two Cities director Ralph Thomas. In case audiences at the time were concerned that this would simply transplant Simon Sparrow to revolutionary Paris, Bogarde apparently commented on this according to British fan magazine Picturegoer. He states that this was why he was keen for Thomas to direct – he would be able to recognise any appearance of his Doctor character and this could then be removed (31st August, 1957, p. 10).

These two sides of Carton’s character are not as divergent as some of Bogarde’s earlier roles in films we have screened – most notably in Esther Waters (1948) and Hunted (1952). But it contrasts to the less complex roles Bogarde played after Cast a Dark Shadow – The Spanish Gardener (1956), Ill Met by Moonlight (1957), Campbell’s Kingdom (1957) and, most significantly, the third in the popular series of Doctor films: Doctor at Large (1957). The films in this series were helmed by A Tale of Two Cities director Ralph Thomas. In case audiences at the time were concerned that this would simply transplant Simon Sparrow to revolutionary Paris, Bogarde apparently commented on this according to British fan magazine Picturegoer. He states that this was why he was keen for Thomas to direct – he would be able to recognise any appearance of his Doctor character and this could then be removed (31st August, 1957, p. 10).

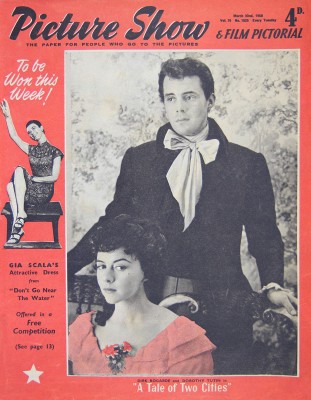

There is, unsurprisingly, a difference between the film’s reception in popular fan magazines and film periodicals. Picturegoer’s review places Bogarde centrally. It considers it his most original performance since he started paying Simon Sparrow, and questioning whether another Dickens adaptation of the novel was necessary (1st of March 1958). Fellow British fan magazine Picture Show’s premiere also mentions Bogarde, though it is more respectful of Dickens and his relevance (8th of February 1958). The March issue of film periodical Films and Filming’s review by Rupert Butler deals with Dickens the most. It praises Jack Conway’s 1935 version and provides more comparison of the source text and the 1958 adaptation than is present in the fan magazines (p. 25). Significantly, the periodical criticises the film for its lack of melodrama: it regrets that Miss Pross’ vanquishing of Madame Defarge (which it describes as ‘one of the most ridiculously splendid bits of Dickens melodrama’) occurs offscreen. The periodical’s understanding of melodrama is further articulated as it complains that the film has a ‘desire to understate the action, to avoid even the slightest risk of excess.’.

There is, unsurprisingly, a difference between the film’s reception in popular fan magazines and film periodicals. Picturegoer’s review places Bogarde centrally. It considers it his most original performance since he started paying Simon Sparrow, and questioning whether another Dickens adaptation of the novel was necessary (1st of March 1958). Fellow British fan magazine Picture Show’s premiere also mentions Bogarde, though it is more respectful of Dickens and his relevance (8th of February 1958). The March issue of film periodical Films and Filming’s review by Rupert Butler deals with Dickens the most. It praises Jack Conway’s 1935 version and provides more comparison of the source text and the 1958 adaptation than is present in the fan magazines (p. 25). Significantly, the periodical criticises the film for its lack of melodrama: it regrets that Miss Pross’ vanquishing of Madame Defarge (which it describes as ‘one of the most ridiculously splendid bits of Dickens melodrama’) occurs offscreen. The periodical’s understanding of melodrama is further articulated as it complains that the film has a ‘desire to understate the action, to avoid even the slightest risk of excess.’.

None of this material touches on the doubling aspect or the relationship between Carton and Darnay. This is, however, key to John Style’s chapter “Dirk Bogarde’s Sidney Carton—More Faithful to the Character than Dickens Himself?” in Books in Motion, Adaptation, Intertextuality, Authorship (2005): 69-86. Style reads the performance of Bogarde as a queer one (p. 69), commenting that he employs the ‘queenish gestures of a diva’ (p. 79). While Style usefully contrasts Bogarde’s performance to that of the ‘wooden’ Guers (p. 72), this use of gendered terms and those relating to sexuality are subjective. This is especially evident in Style’s close analysis of the ‘mirror’ scene in novel and film (pp. 80-81) focuses on its homosexual overtones. It is understandable that these were not commented on at the time, but we thought they were little present in the film text too.

It is perhaps valuable to acknowledge that these aspects appeared more clearly in Bogarde’s later films, and after information about his star image (the revelations of his personal life) came to light. The doubling aspect of A Tale of Two Cities is seen to greater effect in Libel. In our discussion of Libel, we considered that the doubling which saw Bogarde play two roles and how this connected to ideas of homosexuality. (See the discussion and the brief consideration of doubling in A Tale of Two Cities here: https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2018/11/21/summary-of-discussion-on-libel/) Homosexual elements were even more pushed to the fore in Basil Dean’s Victim (1961) which was the first British film to use the term ‘homosexual’. (By happy coincidence, we’ll be screening Victim next time!)

It is perhaps valuable to acknowledge that these aspects appeared more clearly in Bogarde’s later films, and after information about his star image (the revelations of his personal life) came to light. The doubling aspect of A Tale of Two Cities is seen to greater effect in Libel. In our discussion of Libel, we considered that the doubling which saw Bogarde play two roles and how this connected to ideas of homosexuality. (See the discussion and the brief consideration of doubling in A Tale of Two Cities here: https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2018/11/21/summary-of-discussion-on-libel/) Homosexual elements were even more pushed to the fore in Basil Dean’s Victim (1961) which was the first British film to use the term ‘homosexual’. (By happy coincidence, we’ll be screening Victim next time!)

As ever, do log in to comment, or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk and let me know that you’d like me to add your thoughts to the blog.