Our discussion on the film covered various aspects including: its genre; its appeal to female audiences; its ‘Take Three Girls’ approach; its three heroines as role models; male characters; the character of Vivian; the film’s stars; its pace; contemporaneous materials like trade magazines; Warner Brothers studio; the 1938 remake and matters of censorship.

We began with comments on the film’s appeal to female audiences. This was established partly by the film’s genre. Best described broadly as a drama – as the American Film Institute (AFI) categorises it – it moves from melodramatic ups and downs to a more straightforward crime drama. It nonetheless remains focused on its female characters. The film demonstrates a ‘Take Three Girls’ approach, in which we follow the fortunes of three young girls at school into adulthood when they meet again. This allows the film more flexibility than a single heroine, since it can follow three women’s stories.

We began with comments on the film’s appeal to female audiences. This was established partly by the film’s genre. Best described broadly as a drama – as the American Film Institute (AFI) categorises it – it moves from melodramatic ups and downs to a more straightforward crime drama. It nonetheless remains focused on its female characters. The film demonstrates a ‘Take Three Girls’ approach, in which we follow the fortunes of three young girls at school into adulthood when they meet again. This allows the film more flexibility than a single heroine, since it can follow three women’s stories.

This approach also allows for comparison of the film’s characters to one another, thus commenting on those considered the best ‘role models’. This is more complex than we might at first assume from the women’s early days at school. In the opening segment, Mary (Virginia Davis) is portrayed as a fun-loving, knicker-showing girl who gets into trouble for smoking. While Vivian (Dawn O’Day, later known as Ann Shirley) is voted the most popular girl in her class, this is superficial. In fact, since she disapproves of Mary’s free-and-easy attitude she sneakily reports her to teachers. Ruth (Betty Carse) wins an award for academic achievement. Mary is true to herself but not

This approach also allows for comparison of the film’s characters to one another, thus commenting on those considered the best ‘role models’. This is more complex than we might at first assume from the women’s early days at school. In the opening segment, Mary (Virginia Davis) is portrayed as a fun-loving, knicker-showing girl who gets into trouble for smoking. While Vivian (Dawn O’Day, later known as Ann Shirley) is voted the most popular girl in her class, this is superficial. In fact, since she disapproves of Mary’s free-and-easy attitude she sneakily reports her to teachers. Ruth (Betty Carse) wins an award for academic achievement. Mary is true to herself but not one of life’s conformers, Vivian is snooty and privileged, and Ruth hard-working. These characteristics point to their futures. Rich Vivian reveals that she will attend a boarding school, while the less socially advantaged Ruth says she will train for a business career. Neither of them knows what will happen to Mary….

one of life’s conformers, Vivian is snooty and privileged, and Ruth hard-working. These characteristics point to their futures. Rich Vivian reveals that she will attend a boarding school, while the less socially advantaged Ruth says she will train for a business career. Neither of them knows what will happen to Mary….

In fact, Mary’s trajectory ranges considerably. She is next seen in reform school (now played by Joan Blondell), but is soon a steadily-working actress. This is established as she chats about her current show to a hairdresser in the most female of social spaces: the beauty parlour. Coincidentally, Vivian (Ann Dvorak) is occupying the next booth, allowing for them to stage a brief reunion and organise to meet, along with Ruth (Bette Davis), for lunch. At the lunch, it is clear that while Mary and Ruth seem happy enough, Vivian, though she is rich, and married with a young son, is unhappy. This spirals out of control as the film progresses, with her leaving her husband and committing adultery, becoming an absent mother, descending into drugs and poverty, and only at the film’s end partially redeeming her earlier behaviour by sacrificing her life to save her kidnapped son. Meanwhile, Mary finds happiness with Vivian’s husband Bob, and Ruth career fulfilment as governess to Bob and Vivian’s son.

In fact, Mary’s trajectory ranges considerably. She is next seen in reform school (now played by Joan Blondell), but is soon a steadily-working actress. This is established as she chats about her current show to a hairdresser in the most female of social spaces: the beauty parlour. Coincidentally, Vivian (Ann Dvorak) is occupying the next booth, allowing for them to stage a brief reunion and organise to meet, along with Ruth (Bette Davis), for lunch. At the lunch, it is clear that while Mary and Ruth seem happy enough, Vivian, though she is rich, and married with a young son, is unhappy. This spirals out of control as the film progresses, with her leaving her husband and committing adultery, becoming an absent mother, descending into drugs and poverty, and only at the film’s end partially redeeming her earlier behaviour by sacrificing her life to save her kidnapped son. Meanwhile, Mary finds happiness with Vivian’s husband Bob, and Ruth career fulfilment as governess to Bob and Vivian’s son.  The character of a person is placed above their social standing. Nice people who have made a few wrong turns can be happy – especially if they enter the acting profession (!) (Mary), cheats and those unhappy with their privileged lot don’t prosper, though they can make amends (Vivian), and those who calmly get on with things can be quietly happy, if overlooked (Ruth).

The character of a person is placed above their social standing. Nice people who have made a few wrong turns can be happy – especially if they enter the acting profession (!) (Mary), cheats and those unhappy with their privileged lot don’t prosper, though they can make amends (Vivian), and those who calmly get on with things can be quietly happy, if overlooked (Ruth).

We also briefly compared the film’s two main adult male characters. This is encouraged since Vivian leaves the steady and kind, though seemingly unexciting, Bob (Warren William) for the new and apparently charming Michael (Lyle Talbot). We also commented on the way the film directly juxtaposes Bob and Michael. After his son is kidnapped there is a close-up of a desperate Bob, wringing his hands. This is immediately followed by a close-up of Michael’s hands. While at first both men seem to be performing a similar action, it is in fact revealed that he is merely vigorously shaking a cocktail. The only other men involved in the film’s narrative are gangsters.  Most notably Harve (Humphrey Bogart) threatens Michael when he is in debt, delivering him to his shady boss, Ace (Edward Arnold). The latter is coolly calculating, threatening violence while treating Michael with contempt – he will not even halt his macho act of plucking his nose hair without wincing or tearing up. This subtly implies that Michael will be subject so slow and painful torture.

Most notably Harve (Humphrey Bogart) threatens Michael when he is in debt, delivering him to his shady boss, Ace (Edward Arnold). The latter is coolly calculating, threatening violence while treating Michael with contempt – he will not even halt his macho act of plucking his nose hair without wincing or tearing up. This subtly implies that Michael will be subject so slow and painful torture.

Despite the fact that the film has three heroines, these do not have equal billing, screen time, dramatic impact or interest for the audience. Mary is top-billed, with her introduction as an adult character privileged over the other two women, and she ends the film happily after a successful romance. We spent more time discussing Vivian, however. It is far too simplistic to suggest that she is a bad mother who rightly sacrifices herself for her son (in the style of the maternal melodrama). Her situation is more complex. We see her struggle with her relationship with her child who while he is affectionate towards her, seems to prefer his nanny and father. Vivian tells Bob she thinks that having sole charge of her on will be good for her – giving her something to focus on. This does not turn out to be the case though, as when she runs off with Michael she is unable to perform even simple tasks like making sure her son is fed and clean. Other than this, she seems happy to be enjoying Michael’s attentions.

Despite the fact that the film has three heroines, these do not have equal billing, screen time, dramatic impact or interest for the audience. Mary is top-billed, with her introduction as an adult character privileged over the other two women, and she ends the film happily after a successful romance. We spent more time discussing Vivian, however. It is far too simplistic to suggest that she is a bad mother who rightly sacrifices herself for her son (in the style of the maternal melodrama). Her situation is more complex. We see her struggle with her relationship with her child who while he is affectionate towards her, seems to prefer his nanny and father. Vivian tells Bob she thinks that having sole charge of her on will be good for her – giving her something to focus on. This does not turn out to be the case though, as when she runs off with Michael she is unable to perform even simple tasks like making sure her son is fed and clean. Other than this, she seems happy to be enjoying Michael’s attentions.

We commented on Dvorak’s realistic portrayal of Vivian. Her drug addiction and its consequences of poverty are well shown by Dvorak’s convincing acting, and the diminishing of her personal appearance and costume. Vivian’s sacrifice was in some ways inevitable, though surprising in its violence. Earlier we have heard her being hit off-screen. Her final act is far more visible. She throws herself out of a window to draw attention to the whereabouts of her son: she has scrawled this information on her nightgown in lipstick. The film cuts from inside the hotel room to outside, showing Vivian hurtling towards the awning below and hitting the street with a thump.

We commented on Dvorak’s realistic portrayal of Vivian. Her drug addiction and its consequences of poverty are well shown by Dvorak’s convincing acting, and the diminishing of her personal appearance and costume. Vivian’s sacrifice was in some ways inevitable, though surprising in its violence. Earlier we have heard her being hit off-screen. Her final act is far more visible. She throws herself out of a window to draw attention to the whereabouts of her son: she has scrawled this information on her nightgown in lipstick. The film cuts from inside the hotel room to outside, showing Vivian hurtling towards the awning below and hitting the street with a thump.

We also discussed the film’s stars. Despite the film’s short running time, it is not a budget film, but one packed with characters played by stars. Although there are three heroines, a main focus is the star triangle of Mary and Vivian and Bob as Ruth plays a smaller part. Since this was early in Davis’ career, it is not surprising that she played a smaller role, and that the film did not make best use of her talents. We thought the small role Bogart played was more in tune with some of his previous parts, and that Arnold was effective.

Although there is a romantic triangle, the film’s pace means we do not witness Vivian and Bob’s courtship, and that Mary and Bob’s romance takes place at breakneck speed. They are very briefly shown to be attracted to one another as each separately boards the cruise ship to wish friends and family bon voyage. They only spend time together one Vivian has left Bob, with his beach proposal (swiftly following on from offering Ruth a position as governess) coming as a bit of a shock. The newspapers report on this as they note that Bob has divorced and remarried on the same day. The film sustains a rapid pace throughout. In addition to short scenes which establish the time frame (popular songs, historical newspaper headlines) these involve the characters too. After his son’s disappearance Bob, accompanied by Mary and Ruth, begs a judge to intervene in a scene which lasts just a few seconds. We thought the only time the film dragged was the discussion between male workers outside the beauty parlour. These men comment on how Mary has replaced Vivian as Bob’s wife and notice the reappearance of Vivian across the street. This merely recounts the plot and identifies the relationship between the two women who soon meet again. This may have been thought helpful at the time when cinema-goers were more likely to join a screening part-way through.

Although there is a romantic triangle, the film’s pace means we do not witness Vivian and Bob’s courtship, and that Mary and Bob’s romance takes place at breakneck speed. They are very briefly shown to be attracted to one another as each separately boards the cruise ship to wish friends and family bon voyage. They only spend time together one Vivian has left Bob, with his beach proposal (swiftly following on from offering Ruth a position as governess) coming as a bit of a shock. The newspapers report on this as they note that Bob has divorced and remarried on the same day. The film sustains a rapid pace throughout. In addition to short scenes which establish the time frame (popular songs, historical newspaper headlines) these involve the characters too. After his son’s disappearance Bob, accompanied by Mary and Ruth, begs a judge to intervene in a scene which lasts just a few seconds. We thought the only time the film dragged was the discussion between male workers outside the beauty parlour. These men comment on how Mary has replaced Vivian as Bob’s wife and notice the reappearance of Vivian across the street. This merely recounts the plot and identifies the relationship between the two women who soon meet again. This may have been thought helpful at the time when cinema-goers were more likely to join a screening part-way through.

We discussed some contemporaneous extra-filmic material. Trade magazine Motion Picture Herald included a piece on Buster Phelps (who played the son) on the 8th of October. This rightly complimented Phelps on his portrayal, but also noted that he was apparently being paid more than Dvorak. A review of the film had appeared in the same publication a week earlier. This understandably expressed distaste at screening the kidnapping of a child while the tragic Lindberg baby story was still in the headlines. It also asked that the gangsters are seen to be punished.

We discussed some contemporaneous extra-filmic material. Trade magazine Motion Picture Herald included a piece on Buster Phelps (who played the son) on the 8th of October. This rightly complimented Phelps on his portrayal, but also noted that he was apparently being paid more than Dvorak. A review of the film had appeared in the same publication a week earlier. This understandably expressed distaste at screening the kidnapping of a child while the tragic Lindberg baby story was still in the headlines. It also asked that the gangsters are seen to be punished.

This comments on Warner Brothers’ preferred approach of presenting films which were inspired by real-life stories. We also saw Warner Brothers touches in the use of headlines and popular songs to establish time, and the fact it is bang up to date – the date 1932 appears. We noted references to other Warner Brothers films. A magazine article seen in the film which explains that the ‘Three on a Match’ superstition (that if soldiers in the trenches kept a match going long enough to light three cigarettes they would be seen by the enemy and at least one of them killed) was in fact advertising by a Swedish match manufacturer to expand his market. Warner Brothers released a film called The Match King (William Keighley, Howard Bretherton) this same year – which starred Warren William as the title character. Some us also noted footage which was had been recycled from an earlier production (like Public Enemy 1931, William A. Wellman) and the presence of gowns also seen in other films.

This comments on Warner Brothers’ preferred approach of presenting films which were inspired by real-life stories. We also saw Warner Brothers touches in the use of headlines and popular songs to establish time, and the fact it is bang up to date – the date 1932 appears. We noted references to other Warner Brothers films. A magazine article seen in the film which explains that the ‘Three on a Match’ superstition (that if soldiers in the trenches kept a match going long enough to light three cigarettes they would be seen by the enemy and at least one of them killed) was in fact advertising by a Swedish match manufacturer to expand his market. Warner Brothers released a film called The Match King (William Keighley, Howard Bretherton) this same year – which starred Warren William as the title character. Some us also noted footage which was had been recycled from an earlier production (like Public Enemy 1931, William A. Wellman) and the presence of gowns also seen in other films.

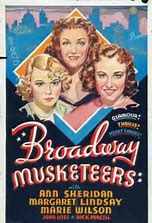

Finally, we spoke about the 1938 remake of the film, Broadway Musketeers (John Farrow). This starred Margaret Lindsay as Isabel (Vivian in the earlier film), Ann Sheridan as Fay (previously Mary), and Marie Wilson as Connie (the Ruth character). In addition to the name changes, and the shifted focus to the ‘Vivian’ character, there are other differences. For instance, they grow up in an orphanage, the son is now a daughter and the ‘match’ superstition is now about smashing glasses. The original and the update appeared six years apart, and significantly range from two years before, to four years after censorship was more strongly implemented via Hollywood’s Production Code. The later version did not include the characters’ childhoods, and therefore avoided altogether showing them as sexualised at an early age. The use of censorship seemed to not serve its intended purpose, however. The remake contains innuendo (and the Mary character is now stripper rather than an actress) and the differences are superficial and not necessarily the aspects audiences focus on. Isabel does not commit adultery since she divorces her husband before she found a new man. Her addiction appears to be legal alcohol rather than drugs which the 1932 film references openly via paraphernalia, intimation of Vivian suffering due to withdrawal, and Harve’s nose-sniffing gesture. Nonetheless she suffers the same fate as in the earlier film, unable to halt the progression of the melodramatic narrative.

Finally, we spoke about the 1938 remake of the film, Broadway Musketeers (John Farrow). This starred Margaret Lindsay as Isabel (Vivian in the earlier film), Ann Sheridan as Fay (previously Mary), and Marie Wilson as Connie (the Ruth character). In addition to the name changes, and the shifted focus to the ‘Vivian’ character, there are other differences. For instance, they grow up in an orphanage, the son is now a daughter and the ‘match’ superstition is now about smashing glasses. The original and the update appeared six years apart, and significantly range from two years before, to four years after censorship was more strongly implemented via Hollywood’s Production Code. The later version did not include the characters’ childhoods, and therefore avoided altogether showing them as sexualised at an early age. The use of censorship seemed to not serve its intended purpose, however. The remake contains innuendo (and the Mary character is now stripper rather than an actress) and the differences are superficial and not necessarily the aspects audiences focus on. Isabel does not commit adultery since she divorces her husband before she found a new man. Her addiction appears to be legal alcohol rather than drugs which the 1932 film references openly via paraphernalia, intimation of Vivian suffering due to withdrawal, and Harve’s nose-sniffing gesture. Nonetheless she suffers the same fate as in the earlier film, unable to halt the progression of the melodramatic narrative.

As ever, do log in to comment, or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk to add your thoughts.