360◦ feedback is an often cited ‘best practice’ model for enabling people to understand how well they perform, what they need to do more of and what they need to improve. Like any method, it needs to be checked to see whether it will work (i.e deliver its intended purpose) and whether it is the best way of achieving that purpose (e.g. are there any unwanted side-effects?). In the case of 360◦ feedback these questions are rarely asked- the first concerns are usually practical (who can give the feedback, how do we collate it) – 360◦ feedback is de facto a ‘good thing’, isn’t it?

360◦ feedback is an often cited ‘best practice’ model for enabling people to understand how well they perform, what they need to do more of and what they need to improve. Like any method, it needs to be checked to see whether it will work (i.e deliver its intended purpose) and whether it is the best way of achieving that purpose (e.g. are there any unwanted side-effects?). In the case of 360◦ feedback these questions are rarely asked- the first concerns are usually practical (who can give the feedback, how do we collate it) – 360◦ feedback is de facto a ‘good thing’, isn’t it?

Nevertheless it is worth stepping back and considering whether the 360◦ approach is:

(i) helpful and (ii) effective…?

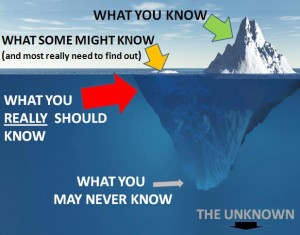

One issue with 360◦ – which you will never find on a 360◦ website (for obvious reasons) is that it is based on judgement and opinion. There is the old adage that “opinion+opinion+opinion=opinions”, in other words any combination of opinions will not necessarily be the truth. This is of course also the case whether you get friend or foe to give you the feedback! For this reason, a lot of people would say ‘don’t bother’.

In fact there is a strong case for the ‘don’t bother to give feedback at all’ viewpoint. It is a question of measurement and assign-ability. What is the feedback measuring? In a stable system 90-95% of performance is due to the system, in other words is not assignable to the individual (Deming 1993). This means that feedback given to the individual will be at best only scratching 5% of what people do. In essence “faults, weaknesses and dereliction of individuals is not the primary door for improvement” – its more effective to work on improving processes and systems (Coens and Jenkins 2000).

(Note: in an unstable system all the feedback should be directed at the boss anyway, not the worker – that is worth a separate blog in itself).

Timeliness of feedback is important: it should relate to specific behaviours for which impact is known and to which the receiver of the feedback can choose to respond to get a different effect. (Coens and Jenkins 2000). Good feedback needs to be delivered in a personal and interactive manner and from a person who is seen as credible. People naturally tend to rationalise feedback from other human beings (Coens and Jenkins 2000, Jacobs 2009), so anonymous feedback can be easily rejected or seen as invalid.

There is a strong argument that where a person is not prepared to/cannot give the feedback face-to-face, then they shouldn’t bother. If they CAN give the feedback face-to-face, they should take responsibility for it but also be prepared for it to be ignored or contested (and take responsibility for the other person’s reaction – anger, tears, hurt, laughter, responsiveness). The best teams are those where this type of discussion is normal, expected and conducted in a good spirit of trust and collegiality.

There is another clue in the usefulness of any method: what ‘checks and balances’ do people have to put on the system to ensure that it is fair on people? If you need to place a ‘system to police the system’ (i.e. who gives the feedback) then , inevitably you will need to have a system to police the police who are policing the system and so on…If any answer is forthcoming that suggests that the method is not impartial, robust or trustworthy – and generates too much work!

It is better to keep feedback down to face-to-face discussion, you simplify it because people take responsibility for the whole. Make sure people know how to give and receive feedback; what, how, when, where, why. Ensure a culture where informal conversations about the work and how it can be improved become the norm. Increase the value of dialogue and discussion on how to improve things within meetings (and move beyond discussion of reporting and giving feedback).

Reading:

Coens and Jenkins (2000) Abolishing Performance Appraisals: why they backfire and what to do instead, Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco, CA.

Deming W.E. (1993) The New Economics, MIT CAES, Cambridge MA.

Jacobs, C.J. (2009) Management Rewired: Why Feedback Doesn’t Work and Other Surprising Lessons from the Latest Brain Science. Penguin Group Portfolio, NY