In a late response to the drama of the football world cup I have a list of lessons learned prompted by HR Grapevine. I have amended their proposed list and have included a couple of items which I have interpreted quite differently, so here is my personal list:

In a late response to the drama of the football world cup I have a list of lessons learned prompted by HR Grapevine. I have amended their proposed list and have included a couple of items which I have interpreted quite differently, so here is my personal list:

1: Don’t be too reliant on one star player

A number of matches have shown balanced teams succeed ahead of those that relied on one star player. Argentina’s Lionel Messi underperformed in the final and the German team got the result. Brazil struggled as soon as Neymar was ruled out through injury. Uruguay were at sea without Suarez. Weeks earlier in the tournament England were too reliant on the Rooney factor and appeared simply not to set up to act as a unit.

The system should be greater than the sum of its parts, and no more so than in a team. Algeria, Mexico and Costa Rica performed above and beyond expectations.

The same is true about the capability of any team.

2: Trying hard will only get you so far

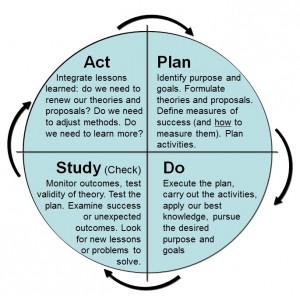

I think the England team were well prepared and earnest in their efforts (despite the hype – both negative and positive – from the tabloids). Best efforts are often a sure fire way to failure (Deming has a lot to say about this). However mediocrity can be turned around – but this needs a transformation in approach.

A huge amount can be achieved by engaged the people who are ‘good enough’ to enable them to perform even better (see point one above).

3: Utilise technology – if it makes sense to do so

FIFA endorsed the use of goal-line technology to deal with the age-old problem of knowing whether a ball had crossed the line for a goal or not. This is not new technology – similar approaches have been used in cricket since 2001 and tennis since 2006. The issue is will it solve the problem? It has been a great success.

Another nice innovation was the marker foam to set positions of defenders in a ‘wall’ at free kicks. Again this was a repeating problem – could we make the job of the referee easier to implement? Simple and effective and in this instance no digital technology in sight.

The first question with technology and innovation is – will it improve what we want to achieve?

4: You need to align team and individual goals

One of the big stories for England in the run up to the world cup concerned whether Wayne Rooney would finally get a goal after 3 unsuccessful tournaments. A bigger question for England fans should have been ‘who cares?’. Ultimately the world cup is not about individual players achieving anything it is about a team wining the championship. All else is a side story.

The problems occur when one person’s goal overrides the team’s goals. Did Rooney shoot when he could make passes to better placed team members? Did he dive into shots which other players were about to take themselves? Did he neglect his defensive duties on the left against Italy allowing them to win the match? There is evidence that points to all of these things. Did England switch off once Wayne had ‘got his goal’ in the game against Uruguay ? Who knows?

The winning German team successfully rotated a whole range of players to do the job. The Netherlands played a recognised centre-forward as a wing back (Dirk Kuyt) and he studiously grafted into that unfamiliar role with great effectiveness. The Dutch even drafted a substitute goalkeeper just for the penalty shootout.

5: Clarity of purpose, identity, belonging and vision pay off

Germany’s plan to recapture the world cup (which they last achieved in 1990) started back in 2000 after a poor showing in the European championships. The German Football Federation invested heavily in the future with new academies and a manager with a long-term plan.

They developed an identity for German international football and engaged players on the basis of playing to that philosophy.

A footnote to this is that German midfielder Sami Khedira picked up an injury in the warm up a few minutes before the start of the cup final and had to be replaced. Khedira will be devastated to have missed the game, but it was clear in the post match celebrations that he revelled in the team’s success and fully identified with the achievement of the team for the part that he had already played in the tournament up to that point (see point 4 above).

An alternative view is offered at HR Grapevine:

‘Partnerships’ might become the new buzzword of the year. But what is this

‘Partnerships’ might become the new buzzword of the year. But what is this