An earlier version of this was first posted on 2nd April 2013

Group working is one of those topics that is awkwardly both straightforward and complex depending upon how you look at it. Conventional wisdom sets us to assume that ‘more heads are better than one’ and this maxim is often a justification for working in teams. But is it always a helpful perspective?

Teams may be created to simply fulfill a structural need; to fill an office space or to organise a number of individuals under the supervision of a particular manager. These are not necessarily good reasons for organising group working.

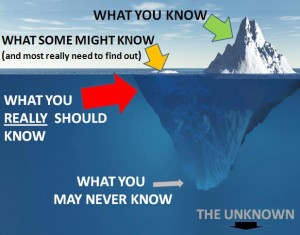

What do we really know about team performance? And, if we are honest with ourselves, do groups always work better than individuals?

The answer, surely, is no. Have you ever sat on a committee and wondered ‘why are we all here?’?

Let’s take a sporting analogy. Put five excellent runners into a relay team. How well do they perform? In many cases, really well. In some cases they are good sometimes and poor another (the British men’s sprint relay team, in four of the last five Olympics and with largely the same personnel have been disqualified – 1996, 2000, 2008, 2012 – but won gold in 2004. Why is there such a wide difference between good and poor performances? It is easy to blame a mistake; incompetence or lack of attention, but the truth lies deeper.

The Ringelmann effect suggests that something different can happen in teams. If people’s personal roles are similar they can be disinclined to put everything into their work (this is a subconscious effect causing ‘free-riding’ rather than deliberate loafing). This effect has been shown in cases where a single worker has been put in a team with ‘non workers’ (i.e. people deliberately faking effort, but not actually doing real work). Even in these instances, the ‘real’ worker is often measured as putting in LESS effort than if they were doing the task on their own. In the classic experiment, assuming that men pulling a rope individually perform at 100% of their ability, apparently two-man groups perform at 93% of the average member’s pull, three-man groups at 85%, with eight-man groups pulling with only 49% of the average individual member’s ability.

So what is the solution? Never work in teams? No this would be a bit foolish, there are better questions…

1. Does the team have a clear sense of purpose?

2. Have we designed team work carefully – goals, roles, work ?

3. Have reasonable and relevant measures of performance been set?

4. Do we agree how to work together?

5. Are people ready to seek improvements as part of their role?

6. Do we encourage trust and mutual respect in the team?

7. Are our relationships based on an understanding of 1-5 above?

So, reverting to my previous blog on teamwork, we must focus on our purpose, our goals, understand our differing roles, agree how we work together at a practical level and look to build positive working relationships based on mutuality and trust.

Like anything in life, if we have a team of people, we need to regularly re-consider the purpose of the team. Do we have a team because it adds to achieving the purpose, or is it just because we have always had a team?

Next time you are in a turgid committee meeting, or your project team has ground to a halt, have a think about how the group could work better…

Further reading:

Beckhard, R. (1972) Optimizing Team Building Effort, J. Contemporary Business. 1:3, pp.23-32

Ingham, A.G., Levinger, G., Graves, J., & Peckham, V. (1974). The Ringelmann effect: Studies of group size and group performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 10, 371–384.

MacDonald, J. (1998) Calling a Halt to Mindless Change, Amacom, UK

Are the same old issues arising in your team?

Are the same old issues arising in your team?