By Cindy Vallance @cdvallance

In my most recent blog I discussed the ambitious vision, purpose and values that those in the Social Sciences Change Academy are working to exemplify, individually and collectively.

But are aspirations sufficient? Of course not. Ideas make us feel good only for the amount of time we are in a room talking about them or only for the amount of time it takes to share an email with yet another good idea.

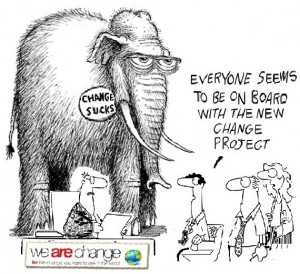

We could…we should…why don’t we?…

That is not to say we shouldn’t share good ideas. The last thing we should do is stop the flow of creativity that can lead to positive changes. But whose responsibility is it to implement these good ideas? Who are the “we” that we so often reference?

I have written quite a lot about self awareness and personal responsibility in these blogs. I firmly believe that what each of us does is key to our collective success. There is a common expression that there is no “I” in team (in English at least), but every action within every team’s plan needs an “I” to make it happen.

If I have an idea for something that should happen or change it is my responsibility to take the next step to try and make it so.

If it is in an area within my range of responsibility to make happen then ‘the buck stops with me.’ If it is a simple thing I can do on my own then I should just get on with it. If it is more than a one person job and I have people within my immediate frame of reference that I can galvanise, then I need to determine how to get these people on board to agree and to support putting the idea into action.

If my idea is one that is beyond the scope of what I can personally do anything about to make happen but I truly believe in it, I still need to find a way to influence people who can then decide to make it happen.

If it is an idea I really care about, I must not give up.

But successful implementation is one of the most difficult parts of change and a significant reason why change efforts so often fail. So what do we need to do? Here are some simple questions to ask ourselves

What is the outcome I/we want to achieve? (vision)

Why should I/we do it? (purpose and values)

How should I/we go about achieving it? (implementation plan)

And on the implementation plan…for the team this must include: what will happen, when it will happen, and who will take responsibility to make it happen. The implementation process for each person within the team is the same: what I will do, when I will do it, and my commitment made real by reliably delivering on what I have promised.

How should I/we track progress? (project management)

How will I/we know if we have succeeded? (evaluation/reflection/adjustment)

So how do we turn aspiration to implementation? It is up to me… It is up to us.