RESILIENCE & LIGHT: Contemporary Palestinian Art

Studio 3 Gallery, 11 April to 18 May 2013

The works of art in this exhibition have been brought to Canterbury from Gaza, London, Venice, Paris, and Dubai as a result of the collaboration between Studio 3 Gallery and Arts Canteen, a London-based cultural venture whose aim ‘is to explore artistic relationships between the Middle East and Mediterranean regions and diverse audiences across Europe’. Our intention in working together has been to celebrate the extraordinary creativity of contemporary Palestinian artists.

The title Resilience and Light refers to two qualities shared by this otherwise remarkably diverse body of work: firstly, the resilience required by artists to create art in conditions of conflict, suffering and exile; secondly, the desire to illuminate through art lived experiences so that they speak to universal human concerns such as fear and despair, but also freedom and hope. As the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish put it, in a verse quoted by Hazem Harb in the title of a work shown for the first time in this exhibition, ‘there is much on this earth worth living for’. In this poem, Darwish associates fondly recalled personal memories – ‘the aroma of bread at dawn, a woman’s point of view about men…’ – as he builds towards a final stanza dedicated to ‘the Lady of Earth… Palestine’.

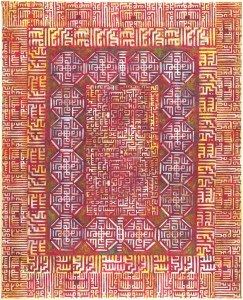

Laila Shawa is one of the preeminent figures in Palestinian art. She trained in Rome and Salzburg in the early 1960s, counting among her teachers Renato Guttuso, Giorgio de Chirico and Oskar Kokoschka. Among her best-known works are the stained glass windows of the Rashad Shawa Cultural Centre in Gaza (constructed 1976-88). Her recent work in this exhibition shows a deep concern with the position of Palestinian women and children, and also asks far-reaching questions about cultural identity through bringing traditional Arabic geometrical designs and calligraphy into bold juxtaposition with the visual conventions of Western Pop and Op art. Shawa states that: ‘my work offers a synthesis of past and present ideas, formal, personal and political, into a powerful contemporary vision of Islamic popular culture.’

Taysir Batniji, Hazem Harb, Mohammed Joha and Hani Zurob represent a younger generation of Palestinian artists, many of whom create their art in exile. Their work is often hybrid in form, combining or switching between painting, photography, film and installation art. As Kamal Boullata has written of Zurob: the Palestinian artist making art in Europe but outside of European art traditions, following what Arthur C. Danto has called ‘the end of art’, occupies a very particular cultural position. The thematic exploration of memory, family and place in the work of these artists is perhaps closer to the Arab literary tradition than to any contemporary artistic movement. The result, as Jean Fisher has argued, is a ‘Palestinian’ art that is more humanistic than propagandistic, sustaining a narrative of ‘lives lived in the space between hope and despair’.

I am most grateful to Aser El Saqqa, who proposed this exhibition, organized the loan of works and co-curated it with me in Studio 3 Gallery. It has been a genuine pleasure to collaborate with Aser and Arts Canteen. Both Aser and I owe a huge debt of gratitude to the artists who have so generously lent their work: Taysir Batniji, Hazem Harb, Mohammed Joha, Laila Shawa, Hani Zurob, and also Raed Issa and Majed Shala. Many thanks to Jean Fisher for the eloquent introduction she has provided to this online catalogue. Thanks also to Zoe Floyd for working on the artists’ biographies. A special thank you to Rhiannon Jones, Studio 3’s tireless and dedicated intern, for all of her help in supporting the exhibition. Thank you also to all of the Studio 3 Gallery volunteers, and to the staff of the School of Arts at the University of Kent.

Ben Thomas (Curator of Studio 3 Gallery)

Resilience and Light – An Introduction

In the context of ‘globalised’ artistic practices, when artists generally reject ‘nationalist’ labels, why does it matter that there should be a category named ‘Palestinian’ art, and what, if anything, would characterise it? To give even a partial answer to this, one needs to think back to a fledgling Palestinian national modernity emerging during the mid-1800s under Ottoman and later British colonial rule, but then cruelly curtailed by the formation of the state of Israel in 1948, when the majority population were either killed or forced into exile. In that year’s edition of the Venice Biennale, what was to have been a ‘Palestine’ pavilion was renamed ‘Israel’. Palestinian intellectual culture – its paintings and libraries – was stolen from homes and institutions by the colonisers and is now largely inaccessible to its true inheritors. Subsequently, as Kamal Boullata relates in Palestinian Art from 1850 to the Present, Palestinian artists remaining in the occupied territories were subjected to harassment by the Israeli state – the closure of exhibitions, the destruction of art works, and throughout the 1960s the prohibition of the use of the colours of the Palestinian flag. Destruction of culture is but one facet of what Ilan Pappe in The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine has called ‘memoricide’: to claim legitimacy, the coloniser typically erases or appropriates the signs of the indigenous population.

Censorship of Palestinian artists has, however, continued beyond Palestine-Israeli borders. Two recent incidents come to mind: firstly, the cancellation, after initial acceptance, of Emily Jacir’s proposal stazione for the 2009 edition of the Venice Biennale. Jacir’s project was to add Arabic translations to the names of the vaporetto stops along the Grand Canal in recognition of the historical links between Venice and Arabic culture. No explanation has ever been given for the cancellation. Secondly, in 2011 Larissa Sansour was shortlisted for the Lacoste-sponsored photography prize by the Musée de l’Elysée in Lausanne to develop a series of photographs, Nation Estate, which satirically relocated Palestinian cities to a skyscraper. But, according to Sansour, Lacoste claimed her submission was ‘too pro-Palestinian’, rejected her proposal and asked her to sign a statement saying that she withdrew from her nomination ‘in order to pursue other opportunities,’ which she refused. Lacoste later denied this, claiming that the work was inappropriate to the competition theme. To its credit, the museum dissolved its relationship with Lacoste and offered Sansour a separate exhibition.

What, then, does it mean for the work of an artist of Palestinian heritage to be accused of being ‘too pro-Palestinian’? Is this not tantamount to insisting one rejects ones own being? We here encounter a common, willful slippage between the political and the ethnic by ‘outside’ institutions, whose motives are by no means transparent. But it illustrates the restrictions and contradictions that surround the cultural productions of Palestinians. Despite the UN recognition in November 2012 of Palestine as a ‘non-member’ state (which, it seems, has finally enabled a ‘Palestine Pavilion’ for the 2013 Venice Biennale), Palestinians remain a stateless nation, united as a people by commonly held meanings that are based in cultural and historical belonging to a defined geography. To paraphrase Edward Said, just because there is no Palestinian state doesn’t mean there are no Palestinians. In so far as poetry was traditionally the primary art form of Arabic culture, Palestinian visual media have tended towards the metaphoric or satirical, speaking to the pain of life in exile – as in the paintings of Hani Zurob – or the absurdities of life under occupation – as one sees with Sansour and the films of Elia Suleiman – rather than the overtly propagandist. It is therefore in this context that the category ‘Palestinian’ art retains a resonance beyond nationalist ascriptions, as that which sustains cultural memory and circulates the Palestinian narrative as lives lived in the space between hope and despair.

Professor Jean Fisher (Art and Design Research Institute, Middlesex University London)

Artists’ Biographies

Taysir Batniji

My Mother, David and Me, 2012, film

Taysir Batniji’s multidisciplinary artistic output addresses Palestinian reality by focusing on displacement, transition and the impossibility of movement. Although trained as a painter, Batniji has worked since the 1990s mainly with installation and performance: mediums which perhaps suit his transitory lifestyle between Palestine and France. Since 2001, Batniji has focused on photography and video, seeking to document Palestine in a subtle and systematic way. His works are, therefore, inseparable from the social, political and cultural context of Palestine.

Born in Gaza in 1966, Taysir Batniji studied art at Al-Najah University in Nablus on the West Bank from 1985-92. In 1994 he was awarded a fellowship to study at the École des Beaux-Arts, Bourges, France, where in 1997 he graduated with a DNSEP (Higher National Diploma in Plastic Expression). Since then he has divided his time between France and Palestine, developing an interdisciplinary practice including drawing, painting, installation and performance, often closely related to his heritage. He has participated in numerous international exhibitions in Europe and beyond. During the 52nd Venice Biennale, Batniji was part of Palestine c/o Venice (2009) and the following year La Biennale Cuvee, Linz, Austria (2010). He was the Abraaj Capital Art Prize winner 2012 and his most recent project is an installation with soap, L’homme ne vit pas seulement de pain, for the Marseille-Provence 2013, European capital of culture.

Hazem Harb

I will wait for you forever, 2010, mixed media on collage and canvas, 140 x 200cm

There is much on this earth worth living for, 2010, mixed media on collage and canvas, 140 x 200cm

Hazem Harb’s artwork is concerned with the human suffering endured in contested, war-torn Gaza. Having spent his childhood and teenage years in Gaza, his artwork aims to be an apolitical and humanistic account of on-going conflict within the region. Born in 1980 in Gaza City, Harb currently lives and works between Rome and Dubai. In 2004, Harb enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome and graduated from the European Institute of Design in 2009. Harb’s work has been exhibited internationally in group and solo exhibitions worldwide. His first solo exhibition in London was in 2010, Is this your first time in Gaza? In 2011, Harb was awarded a residency at the Delfina Foundation, which was also supported by A. M. Qattan Foundation. Harb has won numerous awards, including being selected as of one ten artists for A. M. Qattan Foundation Young Artist of the Year 2008. While using a variety of techniques, Hazem Harb deals with a number of core themes including war, loss, trauma, human vulnerability and global instability. He continues to explore his own brand of multi‐media, conceptual art using all the tools at his disposal. His most recent solo exhibition, Me and the other half, was shown at Art13 London in 2013.

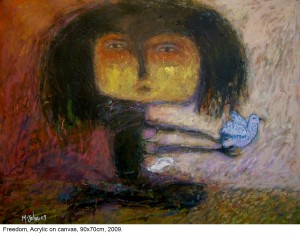

Mohammed Joha

The Umbrella, 2009, acrylic on canvas, 70 x 90cm

Freedom, 2009, acrylic on canvas, 70 x 90cm

The Cat, 2009, acrylic on paper, 70 x 90cm

The Market, 2009, acrylic on paper, 70 x 90 cm

Boy and Fish, 2009, acrylic on canvas, 70 x 90cm

Seven Eyes, 2009, acrylic on canvas, 70 x 90 cm

Mohammed Joha’s paintings are based on his personal life experience in Gaza. Joha’s artworks explore themes such as exile and incarceration. By varying his use of paint in style and technique, his paintings express universal values and incorporate the fantastical. Through embracing freedom of imagination and interpretation, his work aims to overcome cultural barriers. Mohammed Joha was born in Gaza in 1978 and graduated in Art Education from Al-Aqsa University in 2003. Through mixed techniques of collage, painting and photography, much of his work has explored the questions and experiences of childhood, and the loss of innocence and freedom experienced by the current generation of children in Gaza. He was winner of the A. M. Qattan Foundation’s Young Artist of the Year Award in 2004. He has been selected for workshops and residencies in Amman, Jordan and Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris. Besides participating in exhibitions worldwide, he had his first solo exhibition, Dreams in Black and White, at the Mosaic Rooms, London, in 2011. Most recently, his ambitious project, The Jasmine and Bread Revolution, was shown in 2012 at the Courtyard Gallery, Dubai, as well as exhibiting at RichMix, London as part of Despite, 2012. Now living in Italy, Joha is currently working on a project using new techniques with recycled materials.

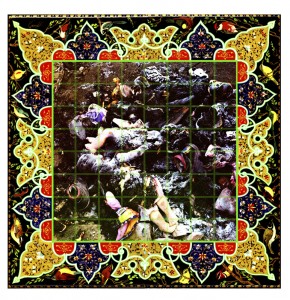

Laila Shawa

Ecstasy, 2008, acrylic and metal leaf on canvas, 200 x 100 cm

Night and the City, 2008, acrylic on canvas, 200 x 100 cm

A River Flows Through It, 2008, acrylic on canvas, 140 x 100 cm

Inside Paradise, 2011, photography and mixed media on canvas, 120 x 120 cm

Trapped I-III, 2011, photography and mixed media on canvas, 100 x 110 cm

We Can (Impossible Dreams), 2011, photography and mixed media on canvas, 120 x 120 cm

Stamp for a Lost Country, 2011, photography and mixed media on canvas, 160 x 100 cm

Meditation 18, 2011, acrylic on canvas, 130 x 100 cm

Defiant and based on a heightened sense of realism, Laila Shawa’s artworks are some of the most influential contemporary works from Palestine. Exhibited internationally, in both private and public collections, her works are rooted in her desire to unveil injustice and persecution. Shawa often draws upon the geometry of Islamic design to represent Islamic popular culture, and also questions cultural identity by contrasting photographic material and Pop Art motifs with these traditional designs. Born in Gaza in 1940, Laila Shawa graduated summa cum laude in Fine Arts from the Italian Accademia di Belle Arti in 1964 and received a diploma in plastic arts from the Accademia San Giacomo in Rome. She exhibited at the Institute for Contemporary Art, London, with her Where Souls Dwell, as part of the AKA Peace exhibition in 2012. Public collections where her works is represented include: the National Galleries of Jordan and Malaysia, the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (Crucifixion 2000: In the Name of God), the British Museum in London and the National Museum for Women in the Arts, Washington D.C. She has been described as ‘one of the few Arab artists to successfully break through barriers in the West’ (Dr Christa Paula). She now lives and works in London.

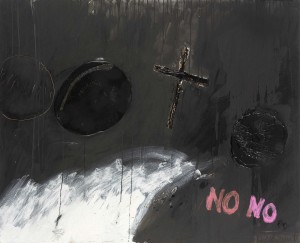

Hani Zorub

The Arab Spring is not yet complete, 2011, mixed media on canvas, 200 x 200cm

One of the defining features of Hani Zurob’s artwork is his abandonment of a collective pictorial rhetoric in favour of subjective expression. This is apparent in paintings that combine abstraction and figuration, and which incorporate imagery found in family photographs. He has explored, through a series of paintings focusing on the image of his young son, themes such as identity, transition and collective belonging. Exiled from Palestine, his work also explores displacement.

Hani Zurob was born in Rafah Refugee Camp, Gaza, in 1976. He graduated with a BA in Fine Arts from Al Najah University, Nablus. In 2006 he was awarded a residency at Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris. His work has been exhibited internationally and is in public and private collections worldwide. The conflicted nature of Palestinian identity, and the condition of exile, is a recurrent theme throughout his work. He has said of his work ‘What I try to do when I paint is to rewrite my life; I try to place myself as a witness of the situations and the events I experience’. Recent work was exhibited at the Institut du Monde Arab, Paris, in Le corps découvert: Art arabe contemporain and at RichMix, London as part of the Despite exhibition. A monograph tracing the development of his work, Between Exits by Kamal Boullata was published by Black Dog Publishing, London (November 2012). Hani Zurob was tipped by The Huffington Post as one of ten ‘international artists to watch in 2013’.