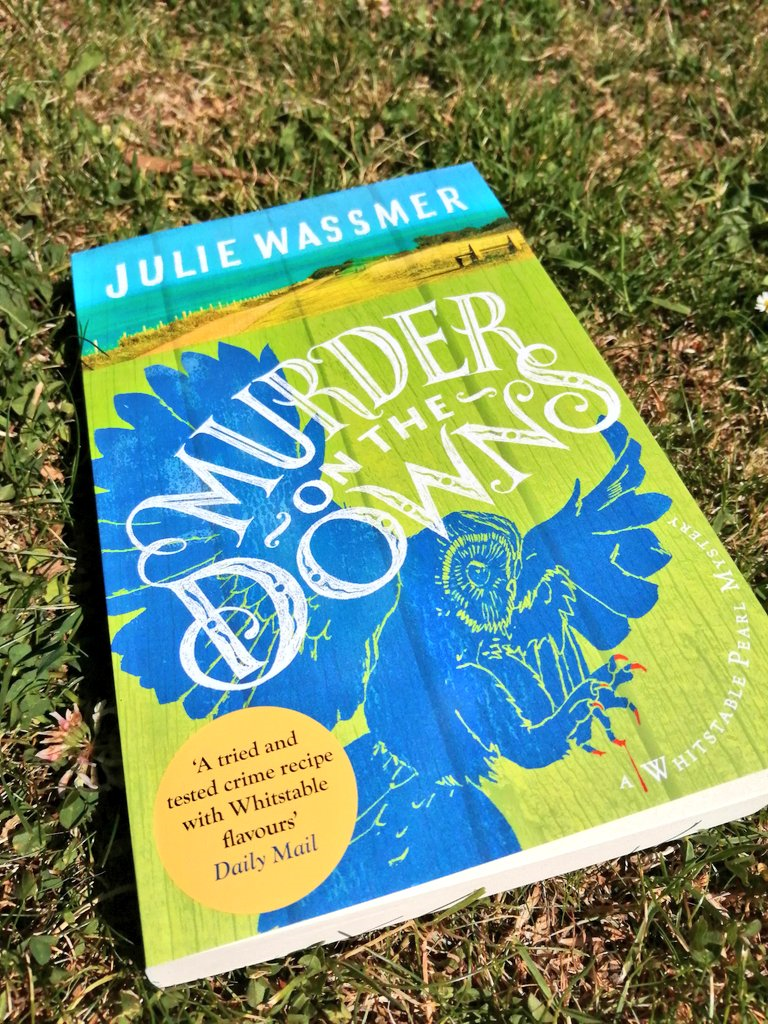

The antagonism between the old and the new lies at the heart of Murder on the Downs, the latest (and strangely prophetic) chapter in the developing ‘Whitstable Pearl’ series of crime novels by Julie Wassmer. It permeates the book – in its people, in places, in ways of thinking. This tension is distilled into what is the real issue at the centre of the book – the clash between technology and the printed word. Pearl Nolan, restaurant-owner-cum-private-detective is constantly checking her smartphone, reading the latest features from the local newspaper, the Chronicle, online long before the published headlines hit The Street. Internet turnaround is leaner, faster, and more readily available than newspapers.

It’s also about the tension between the older generation and the young; whilst Pearl is efficiently navigating her smartphone to read the latest revelations about the case, or texting DCI McGuire (with whom she shares both the investigation as well as her heart), it’s her mother, Dolly, who resorts to picking up and reading an actual newspaper. Although the novel relies on the traditional murder and investigation as its narrative outline, the driving force is its head-on look at media power – the influence it wields, its ability to sway minds, and the lengths people will go to in order to create and control headlines.

It’s also about the tension between the older generation and the young; whilst Pearl is efficiently navigating her smartphone to read the latest revelations about the case, or texting DCI McGuire (with whom she shares both the investigation as well as her heart), it’s her mother, Dolly, who resorts to picking up and reading an actual newspaper. Although the novel relies on the traditional murder and investigation as its narrative outline, the driving force is its head-on look at media power – the influence it wields, its ability to sway minds, and the lengths people will go to in order to create and control headlines.

The central theme of the book concerns the threat to a stretch of countryside by a proposed property development. Wassmer presents a nicely-balanced view from both sides of the argument – those who would protect history and those who advocate for necessary change, in this case the building of affordable homes for a younger generation increasingly forced out of Whitstable by its spiralling house prices. ‘Progress doesn’t have to be a dirty word,’ argues one of its advocates. But there’s a deep-seated desire to protect the area, which mobilises a group of protestors.

‘Throughout history, people have always fought for what they value. Rarely is it given – it has to be earned – and defended with determination, commitment and strength of purpose.’

Reading that clarion-call in the current climate of crumbling arts and the collapse of opera-houses, theatres and concert-halls under the impact of COVID-19 felt prophetic – it feels like a highly appropriate time to be reading the book. As Martha, one of the main characters, observes: ‘Do nothing and there’ll never be change. But everything we do – or we don’t do – makes a difference.’

Wassmer controls the pace and set-pieces of the drama well; the set-piece of the medieval pageant atop the downs has a nice cinematic feel, leading into the lighting of the beacon to symbolise the protest’s public beginning. There’s a Gothic denouement atop the Black Mill (a genuine former working mill that stands at the top of Borstal Hill – location and geographical accuracy remains a constant throughout the series, and is a major aspect of the appeal of the books both for local reader as well as aspiring literary visitors), complete with flashes of lightning and ominous thunder. And the Black Mill is again a significant emblem of the old-versus-new dynamic – standing in the mill, Pearl is afforded a view of the estuary, in whose waters stands the modern wind-farm, its red lights glowing in the darkness. There are also some gently comic touches; a moment of, if not coitus interruptus, then coitus notquitestartedus in a secluded meadow, and a nicely tart dig at a paper’s presumption of impartiality:

Wassmer controls the pace and set-pieces of the drama well; the set-piece of the medieval pageant atop the downs has a nice cinematic feel, leading into the lighting of the beacon to symbolise the protest’s public beginning. There’s a Gothic denouement atop the Black Mill (a genuine former working mill that stands at the top of Borstal Hill – location and geographical accuracy remains a constant throughout the series, and is a major aspect of the appeal of the books both for local reader as well as aspiring literary visitors), complete with flashes of lightning and ominous thunder. And the Black Mill is again a significant emblem of the old-versus-new dynamic – standing in the mill, Pearl is afforded a view of the estuary, in whose waters stands the modern wind-farm, its red lights glowing in the darkness. There are also some gently comic touches; a moment of, if not coitus interruptus, then coitus notquitestartedus in a secluded meadow, and a nicely tart dig at a paper’s presumption of impartiality:

“We do try to give a balanced view on most issues.”

“You mean you like to sit on the fence to please both parties ?”

The mill; the silver Lexus (and it always IS a silver Lexus); the wind farm; the ancient woodland of Benacre Wood; the historic Crown on the Downs; like pieces in the chess game which is also a theme in the novel, these elements are, as much as the characters themselves, symbols of the town and its identity, the traditional and historic (such as the remnants of the historic Blean Woods) pitched against the silver Lexus, a metaphor for all the DFLs (Down From Londoners) who have no respect for the town’s way of life.

So, the book turns out to be (as one might expect from a writer) a hymn to the passing of newspapers and the decline of the printed word as the internet becomes increasingly widespread. “In the last fifteen years over two hundred local newspapers have disappeared in the country, and more than half the towns have no local newspaper at all” reflects Chris Latimer, whose family own the local Chronicle. “A good local paper holds a mirror to its own community.” A sentiment true not just of this book, but also of the unfolding series as a whole.

Maybe the smartphone is the real sinister figure casting a shadow across the whole the novel after all…

Murder on the Downs is published by Little, Brown UK.

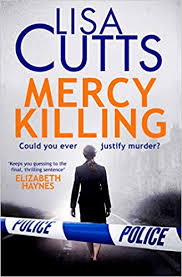

What Cutts is exploring in the novel, a gritty, urban police procedural informed by her own experiences as an investigating detective, is the idea that bad things can come from good intentions, a concept which affects all the characters involved in the drama, and which sees each of them grappling with their own conflicts and making uncomfortable liaisons. At the head of the case, DI Powell is fully aware that, to solve the case, he must ‘break bread with a monster,’ and knows precisely the moment when he crosses the line. His personal dance with the devil involves a meeting with the less than wholesome Martha, who leads the Volunteer Army, a group of local people which at first seems to have a positive mandate – those involved are ‘trying to make it as safe for people as they can about living with sex offenders around them and we want to work with the police. We’re trying to do our bit to help.’ Yet urban vigilantes taking the law into their own hands is never a good idea, and later in the book the reason for the creation of the group is revealed, arising as it does from yet another evil beginning.

What Cutts is exploring in the novel, a gritty, urban police procedural informed by her own experiences as an investigating detective, is the idea that bad things can come from good intentions, a concept which affects all the characters involved in the drama, and which sees each of them grappling with their own conflicts and making uncomfortable liaisons. At the head of the case, DI Powell is fully aware that, to solve the case, he must ‘break bread with a monster,’ and knows precisely the moment when he crosses the line. His personal dance with the devil involves a meeting with the less than wholesome Martha, who leads the Volunteer Army, a group of local people which at first seems to have a positive mandate – those involved are ‘trying to make it as safe for people as they can about living with sex offenders around them and we want to work with the police. We’re trying to do our bit to help.’ Yet urban vigilantes taking the law into their own hands is never a good idea, and later in the book the reason for the creation of the group is revealed, arising as it does from yet another evil beginning.

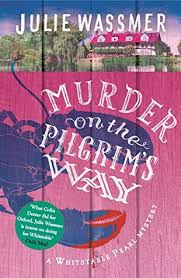

Taking her heroine out of both her seaside town of Whitstable and her usual haunt of Canterbury, Wassmer instead opts to place her in an idyllic rural retreat near Chartham, setting the scene for that classic of the crime genre, the Country House Murder. It is a bold move, placing the book directly in the lineage of a British literay tradition reaching from Agatha Christie, Dorothy L Sayers and J Jefferson Farjeon to later luminaries such as PD James and Reginald Hill. This affords plenty of opportunities for vivid description of rural scenes and lakeside trysts which perfectly capture the lazy haze of an English countryside lulled by summer’s warmth, as well as giving Wassmer the opportunity to explore a more focused arena.

Taking her heroine out of both her seaside town of Whitstable and her usual haunt of Canterbury, Wassmer instead opts to place her in an idyllic rural retreat near Chartham, setting the scene for that classic of the crime genre, the Country House Murder. It is a bold move, placing the book directly in the lineage of a British literay tradition reaching from Agatha Christie, Dorothy L Sayers and J Jefferson Farjeon to later luminaries such as PD James and Reginald Hill. This affords plenty of opportunities for vivid description of rural scenes and lakeside trysts which perfectly capture the lazy haze of an English countryside lulled by summer’s warmth, as well as giving Wassmer the opportunity to explore a more focused arena.

Both women stressed the importance of research to their writing. Cutts attended an autopsy in order to inform part of one of her novels; she came away, she says, awed by the amount of work and commitment which goes in to them. “They’re not as clean and quick as they are on TV; they take hours!” she declared, whilst ruefully admitting to having worn the ‘wrong sort of shoes’ as she hadn’t anticipated standing for so long. For her Whitstable-based series featuring private detective-cum–restaurant-owner, Pearl Nolan, Wassmer spent last summer exploring locations including Reculver, Sheppey and Oare in order to widen the scope of her character’s travels. “Details are important,” Wassmer stated: “you don’t want a sackful of mail criticising a point in your book!” Although she balanced this by admitting that, for her, it is important to remember that, after all, it is the writer’s own world, one that they have created, and that on one level they can do what they like. Wassmer has had reviews where readers take issue with the geography of Whitstable as it appears in her books, with particular roads not leading to exactly the right road. Cutts says she often ends up shouting at television programmes; “No, no, no; you didn’t caution him!” before adding reflectively “it’s why I don’t really watch much crime drama on TV…”

Both women stressed the importance of research to their writing. Cutts attended an autopsy in order to inform part of one of her novels; she came away, she says, awed by the amount of work and commitment which goes in to them. “They’re not as clean and quick as they are on TV; they take hours!” she declared, whilst ruefully admitting to having worn the ‘wrong sort of shoes’ as she hadn’t anticipated standing for so long. For her Whitstable-based series featuring private detective-cum–restaurant-owner, Pearl Nolan, Wassmer spent last summer exploring locations including Reculver, Sheppey and Oare in order to widen the scope of her character’s travels. “Details are important,” Wassmer stated: “you don’t want a sackful of mail criticising a point in your book!” Although she balanced this by admitting that, for her, it is important to remember that, after all, it is the writer’s own world, one that they have created, and that on one level they can do what they like. Wassmer has had reviews where readers take issue with the geography of Whitstable as it appears in her books, with particular roads not leading to exactly the right road. Cutts says she often ends up shouting at television programmes; “No, no, no; you didn’t caution him!” before adding reflectively “it’s why I don’t really watch much crime drama on TV…” As usual, the novel is deeply rooted in its depiction of Whitstable itself, the book really a hymn to the town’s distinctive qualities; windswept beaches, boutique shops, a decorous high street, and wonderfully-titled alleyways. Forays into Canterbury are equally grounded in the real geography of the city, littered with streets and places which will be familiar to local readers (there’s quite a pleasurable feeling to be able to recognise places you know well in books, somehow…).

As usual, the novel is deeply rooted in its depiction of Whitstable itself, the book really a hymn to the town’s distinctive qualities; windswept beaches, boutique shops, a decorous high street, and wonderfully-titled alleyways. Forays into Canterbury are equally grounded in the real geography of the city, littered with streets and places which will be familiar to local readers (there’s quite a pleasurable feeling to be able to recognise places you know well in books, somehow…).