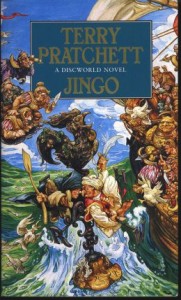

I’ve loved Terry Pratchett’s Discworld sequence of novels for years, without really knowing why. I’ve always avoided trying to pinpoint exactly what it is about Pratchett’s prose that is funny: analysing humour is a bit like prodding a balloon with a pin – at some point, it’s going to burst.

I’ve loved Terry Pratchett’s Discworld sequence of novels for years, without really knowing why. I’ve always avoided trying to pinpoint exactly what it is about Pratchett’s prose that is funny: analysing humour is a bit like prodding a balloon with a pin – at some point, it’s going to burst.

But a moment of revelation struck me recently whilst reading Jingo, the twenty-first instalment in the prolific series.

People’s Exhibit A: Corporal Nobby Nobbs, a member of the City Watch, is so awful to behold that he has been given a certificate to prove he’s actually human. He is endeavouring to express some difficult sentiments – i.e. his lack of attractiveness of girls – to Sergeant Angua, a female colleague.

“What I’m sayin’ is, as you get older, you know, you think about settlin’ down, findin’ someone who’ll go with you hand in hand down life’s bumpy highway.”

“But I just don’t seem to meet girls,” Nobby said.” Well, I mean, I meet girls, and then they rush off.” (p.56).

Brilliant. Here, it’s what’s missing in the last sentence that’s the key to the humour. Left unsaid is the whole ‘I meet girls but they’re traumatised by my being hideous’ sentiment; what the reader gets is the first part and the last part, but without the middle section linking the two. This means that the bit about girls leaving in horror comes a lot sooner that we expect; and what a wonderfully concise manner of expressing it. ‘They rush off.’

People’s Exhibit B: two more officers of the City Watch, Commander Vimes and Captain Carrott, have just had one of their number kidnapped, and need to give chase in a boat. But they don’t have one, so they need to commandeer one from a disreputable smuggler named Captain Jenkins. Vimes, ever the figure of reasoned action, opens proceedings.

“Ah, Captain Jenkins! This is your lucky day!”

“It is ?” he said.

“Yes, because you have an unrivalled opportunity to aid the war effort.”

“I have ?”

“And also to demonstrate your patriotism,” Carrott added.

“I do ?”

“We need to borrow your boat.”

“Bugger off!” (p.217)

In this passage, it’s the juxtaposition of smooth legalese-speak and blunt coarseness that creates the humour; Vimes’ wonderfully articulate, law-abiding sentences offering the ship’s captain a chance to redeem himself, and the captain missing this completely, comprehending only what is expected of him when told directly – we need to borrow your boat – and his blunt response.

It’s the ideas of concision and conflation operating in Pratchett that gives rise to the humour: juxtaposing two ideas which imply an awful lot that is left unsaid, and expressing them in a brief yet telling manner. And often these two ideas collide because they are almost antithetical: articulacy and vulgarity, logic and confusion, grace and slapstick, great wisdom and downright stupidity (the latter usually, in Pratchett, The Law).

It’s the ideas of concision and conflation operating in Pratchett that gives rise to the humour: juxtaposing two ideas which imply an awful lot that is left unsaid, and expressing them in a brief yet telling manner. And often these two ideas collide because they are almost antithetical: articulacy and vulgarity, logic and confusion, grace and slapstick, great wisdom and downright stupidity (the latter usually, in Pratchett, The Law).

Pratchett’s humour also implies that his readers are intelligent and able to work out the parts that are left unexpressed; you admire his humour and are also able to pat yourself on the back for having worked it out (as he wants you to). Clever, eh ?

I’m fully aware that this brief examination of how the humour works in Pratchett’s writing may not have convinced you. It may not have worked At All. But the real way for it to get you, as with music, is to experience it for yourself. Read the books. They won’t let you down.

Posted by Daniel Harding, Deputy Director of Music at the University of Kent. Click here to view his Music Matters blog.

For over forty years, Philip Larkin wrote to Monica Jones, the woman who shared his life. As Anthony Thwaite, Larkin’s literary executor and friend,

For over forty years, Philip Larkin wrote to Monica Jones, the woman who shared his life. As Anthony Thwaite, Larkin’s literary executor and friend,

“The music in that show isn’t hip hop … or rock…or anything essential to culture.”

“The music in that show isn’t hip hop … or rock…or anything essential to culture.”

I’ve loved Terry Pratchett’s Discworld sequence of novels for years, without really knowing why. I’ve always avoided trying to pinpoint exactly what it is about Pratchett’s prose that is funny: analysing humour is a bit like prodding a balloon with a pin – at some point, it’s going to burst.

I’ve loved Terry Pratchett’s Discworld sequence of novels for years, without really knowing why. I’ve always avoided trying to pinpoint exactly what it is about Pratchett’s prose that is funny: analysing humour is a bit like prodding a balloon with a pin – at some point, it’s going to burst. It’s the ideas of concision and conflation operating in Pratchett that gives rise to the humour: juxtaposing two ideas which imply an awful lot that is left unsaid, and expressing them in a brief yet telling manner. And often these two ideas collide because they are almost antithetical: articulacy and vulgarity, logic and confusion, grace and slapstick, great wisdom and downright stupidity (the latter usually, in Pratchett, The Law).

It’s the ideas of concision and conflation operating in Pratchett that gives rise to the humour: juxtaposing two ideas which imply an awful lot that is left unsaid, and expressing them in a brief yet telling manner. And often these two ideas collide because they are almost antithetical: articulacy and vulgarity, logic and confusion, grace and slapstick, great wisdom and downright stupidity (the latter usually, in Pratchett, The Law).