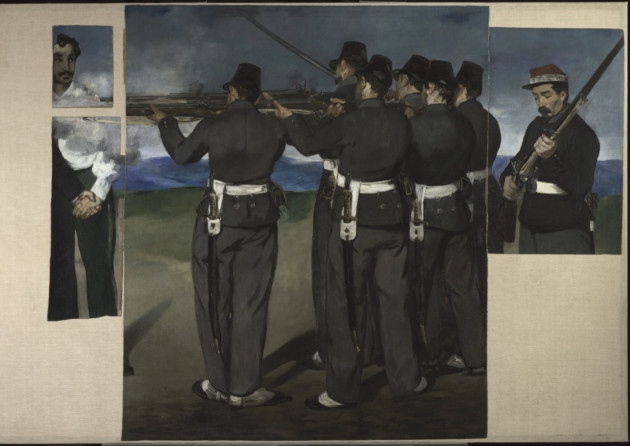

The four pieces of canvas which comprise the reconstructed Execution of Maximilian by Manet currently hang on the wall in the Special Exhibitions room of Canterbury’s The Beaney. I’d seen the painting before, many years ago, in the National Gallery, but on visiting it recently in the walled city, I was struck anew by its power.

Large enough to make the viewer an implicit spectator at the scene, what shocks the most even after all this time is the matter-of-fact approach of the figure on the right, the soldier preparing his rifle for the finishing coup-de-grace. The collision of the act of violence – somehow made all the more vibrant because the pieces on which the emperor was painted have been lost, and only his hand remains to clasp that of one of his comrades, also facing execution – and the practicality of the soldier readying his rifle serves to heighten the tension in the painting.

An earlier lithograph of the same scene renders the commonplace even more apparent, as Manet depicts a ragged bunch of street-urchins looking over the wall behind the scene, like everyday gawkers or the tricoteuse, those women who would sit and knit beside the guillotines.

An earlier lithograph of the same scene renders the commonplace even more apparent, as Manet depicts a ragged bunch of street-urchins looking over the wall behind the scene, like everyday gawkers or the tricoteuse, those women who would sit and knit beside the guillotines.

By dressing the Mexican army in French uniform, Manet caused the painting to be too controversial to be displayed during his lifetime. Even now, over one hundred and forty years later, the painting still has an explosive quality.

The painting is on display at the Beaney until Sunday 16 March.

—-

Dan Harding is the Deputy Director of Music at the University. Follow Dan on Twitter.