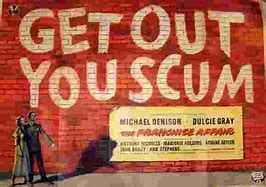

All are very welcome to join us for the fourth of this term’s screenings. We will be showing The Franchise Affair (1951, Lawrence Huntingdon, 95 mins) on Wednesday the 26th of February, 5-7pm, in Jarman 6.

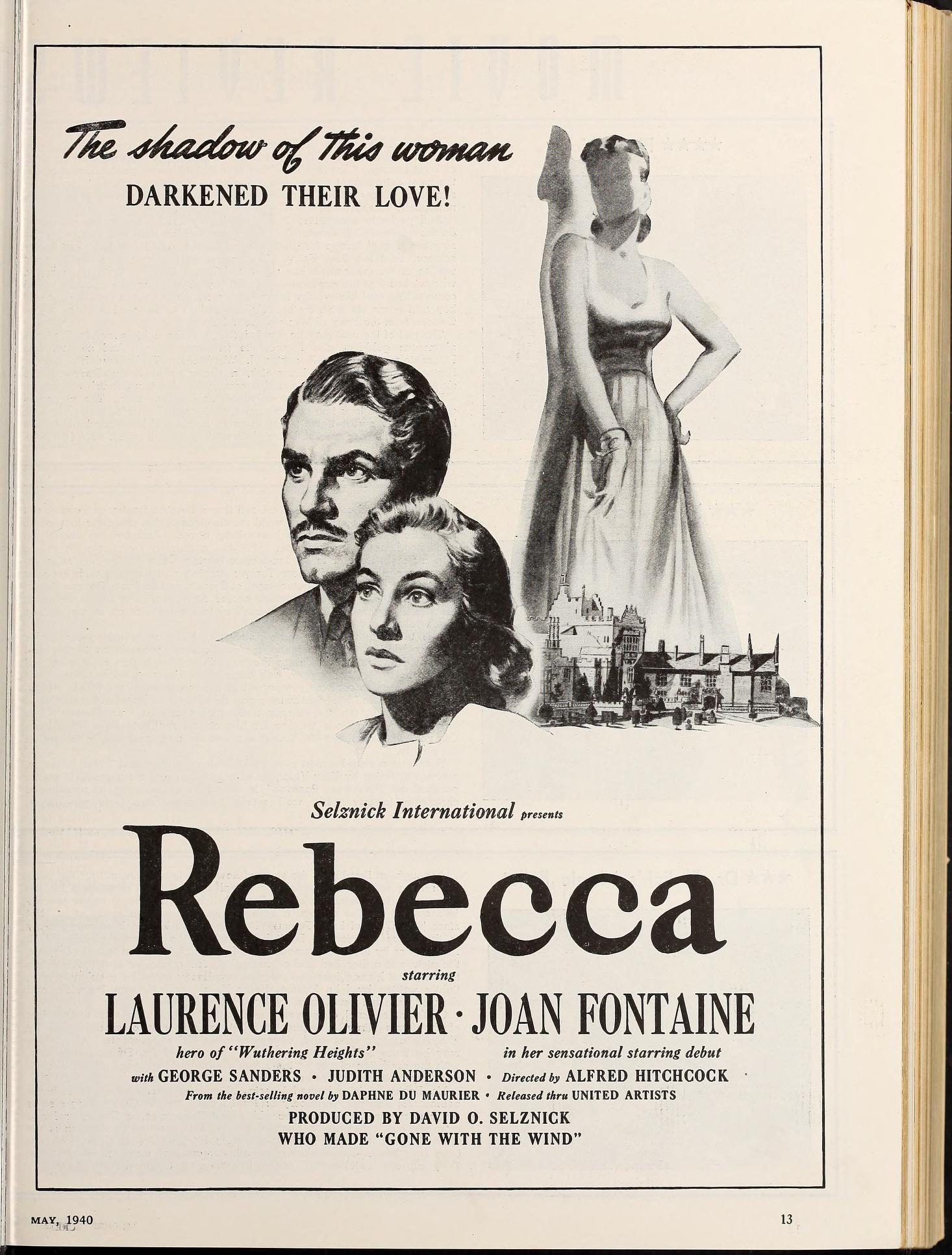

The Franchise Affair is based on Josephine Tey’s 1948 novel of the same name. The third of Tey’s Inspector Alan Grant series of novels, it directly follows 1936’s A Shilling for Candles, adapted as Young and Innocent (1937). (You can see our discussion of this film here: https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2020/01/21/summary-of-discussion-on-young-and-innocent/ )

Grant once more briefly appears, this time played by John Bailey, but the top-billed stars are Michael Denison and Dulcie Gray. Denison, as local lawyer Robert Blair, comes to the aid of Gray’s Marion Sharpe, and her mother (played by Marjorie Fielding). They have been accused of kidnapping and torturing a local young woman, Betty Kane (Ann Stephens). Tey’s plot was inspired by the real-life case of 18th Century maidservant Elizabeth Canning.

The New York Times considered both Tey’s novel and the film to belong to the melodrama genre. On the film’s release in the United States a very brief note labels the film ‘a British-made melodrama’ (3rd June 1952). Two months later, James Kelly reviewed Tey’s The Privateer (written under the name Gordon Daviot) for the same newspaper. In his review, Kelly applies the term ‘melodrama’ to The Franchise Affair and Brat Farrar – Tey’s 1949 non-Alan Grant novel (24th August 1952). Kelly provides more detail, claiming that Tey’s ‘vivid characterization, dispassionate reporting, and crisp writing can lend conviction to improbable melodrama’. Kelly’s view of melodrama is therefore pejorative – it is not believable, and praise is due to Tey for surmounting it.

We can perhaps discuss this in relation to the novel and/or film. In particular, it may be worth considering if the fact that the New York Times labelling of the film as ‘British melodrama’ has additional significance, commenting not just on its country of production, but its treatment of melodrama.

Do join us if you can.