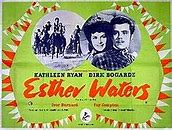

Our discussion of Esther Waters focused on several areas: melodrama and its character stereotypes of (female) victim and (male) villain; the main characters Esther and her lover William Latch; the rhythms of melodrama; the film’s social commentary.

We initially noted that the film was subtler than anticipated, including in relation to expectations raised by extra-filmic fan and trade magazines. While many, though not all, Victorian melodramas seem to function at the level of both fate and character, Esther Waters’ melodrama mostly stemmed from the former. The characters, especially the main couple – Esther (Kathleen Ryan) and William (Dirk Bogarde) – were nuanced rather than stereotypical.

To provide some context, the source material – George Moore’s 1894 novel – was published towards the end of a cycle of ‘Fallen Woman’ novels. These include those written by British women – Elizabeth Gaskell’s Ruth (1853) and Ellen Wood’s East Lynne (1861) – as well as the male British novelists Wilkie Collins’ The New Magdalen (1873) and Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891). Three years after Moore’s novel appeared the perhaps archetypal US melodrama – Charlotte Blair Parker’s play Way Down East – was first staged. D.W. Griffiths’ 1920 silent film version starring Lillian Gish as Anna Moore is one of the most cited silent melodramas. Like many other of the female protagonists in the cycle, Anna is betrayed by the man she loves, gives birth to an illegitimate baby, and is subsequently cast out by society. By contrast, we commented that Esther was a strong heroine who knowingly took decisions to direct her own life and was not the self-sacrificing suffering woman completely at the mercy of others. Similarly, we thought that William was not what some might consider to be the moustache-twirling villain of the piece. (While Bogarde does sport an ill-advised moustache for a fair proportion of the film this appears to be incidental.)

To provide some context, the source material – George Moore’s 1894 novel – was published towards the end of a cycle of ‘Fallen Woman’ novels. These include those written by British women – Elizabeth Gaskell’s Ruth (1853) and Ellen Wood’s East Lynne (1861) – as well as the male British novelists Wilkie Collins’ The New Magdalen (1873) and Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891). Three years after Moore’s novel appeared the perhaps archetypal US melodrama – Charlotte Blair Parker’s play Way Down East – was first staged. D.W. Griffiths’ 1920 silent film version starring Lillian Gish as Anna Moore is one of the most cited silent melodramas. Like many other of the female protagonists in the cycle, Anna is betrayed by the man she loves, gives birth to an illegitimate baby, and is subsequently cast out by society. By contrast, we commented that Esther was a strong heroine who knowingly took decisions to direct her own life and was not the self-sacrificing suffering woman completely at the mercy of others. Similarly, we thought that William was not what some might consider to be the moustache-twirling villain of the piece. (While Bogarde does sport an ill-advised moustache for a fair proportion of the film this appears to be incidental.)

Considering the two main characters in more detail, we especially noted Esther’s resilience and determination. Some of Esther’s strong opinions are connected to her faith – she is one of the Plymouth Brethren. Her very religion therefore goes against the prevailing church of England doctrine dominant at the time– she is a nonconformist. Esther is also notably anti-gambling, in

Considering the two main characters in more detail, we especially noted Esther’s resilience and determination. Some of Esther’s strong opinions are connected to her faith – she is one of the Plymouth Brethren. Her very religion therefore goes against the prevailing church of England doctrine dominant at the time– she is a nonconformist. Esther is also notably anti-gambling, in  opposition to other members of the house, Woodview, in which she goes to work as a kitchen maid, since the estate keeps racing horses. She also does not approve of the penny dreadfuls the other staff read aloud. Esther’s firm stance is reinforced by other characters within the diegesis. Mrs Latch (Mary Clare) is the cook at Woodview, and William’s mother. She states that Esther is a ‘strong’ woman’ – the type her son needs.

opposition to other members of the house, Woodview, in which she goes to work as a kitchen maid, since the estate keeps racing horses. She also does not approve of the penny dreadfuls the other staff read aloud. Esther’s firm stance is reinforced by other characters within the diegesis. Mrs Latch (Mary Clare) is the cook at Woodview, and William’s mother. She states that Esther is a ‘strong’ woman’ – the type her son needs.

It is not just Esthe r’s or other characters’ comments, which reveal her strength, but also her actions. Perhaps surprisingly given Esther’s strong faith, she is seduced by William. Her response to her consequent pregnancy is typically stoic. She decides to keep her baby after William leaves, even though this means she has to quit her current situation, and have her child looked after by others while she finds employment in London. In one of the film’s most melodramatic, and disturbing, scenes, Esther visits her sick baby who is being ‘looked after’ by a woman, Mrs Spires (Beryl Measor), who has multiple children in her care. The woman implies that Esther, and her baby, would be better off if the baby quietly died. Instead of consenting to this outrageous suggestion, or pretending that she has not understood, Esther confronts the woman. She

r’s or other characters’ comments, which reveal her strength, but also her actions. Perhaps surprisingly given Esther’s strong faith, she is seduced by William. Her response to her consequent pregnancy is typically stoic. She decides to keep her baby after William leaves, even though this means she has to quit her current situation, and have her child looked after by others while she finds employment in London. In one of the film’s most melodramatic, and disturbing, scenes, Esther visits her sick baby who is being ‘looked after’ by a woman, Mrs Spires (Beryl Measor), who has multiple children in her care. The woman implies that Esther, and her baby, would be better off if the baby quietly died. Instead of consenting to this outrageous suggestion, or pretending that she has not understood, Esther confronts the woman. She just manages to flee, clutching her baby, only to almost suffer another melodramatic fate: being run over by a horse and carriage. Esther is brave enough to mention the woman’s intentions to the policeman who saves her. His incredulous response (‘it’s 1875!’) further underlines the melodramatic nature of the previous scene, suggesting that such happenings do not occur in modern times.

just manages to flee, clutching her baby, only to almost suffer another melodramatic fate: being run over by a horse and carriage. Esther is brave enough to mention the woman’s intentions to the policeman who saves her. His incredulous response (‘it’s 1875!’) further underlines the melodramatic nature of the previous scene, suggesting that such happenings do not occur in modern times.

Such principled honesty is also seen with Esther’s dealings with other characters. When Fred Parsons (Cyril Cusack), a part-time preacher who has taken a shine to her proposes, she immediately tells him that she has a son. Esther’s truthfulness is rewarded when he apologises for initially being shocked and offers to take on both her and her child. Esther is also honest in front of others. Several years after William’s initial disappearance, he and Esther unexpectedly meet on a crowded train. In response to Williams’ question of where she has been, Esther sharply retorts that she has been looking after his son. She appears to have little regard for what conclusions those around her might draw about her son’s illegitimacy.

Esther’s dealings with other characters. When Fred Parsons (Cyril Cusack), a part-time preacher who has taken a shine to her proposes, she immediately tells him that she has a son. Esther’s truthfulness is rewarded when he apologises for initially being shocked and offers to take on both her and her child. Esther is also honest in front of others. Several years after William’s initial disappearance, he and Esther unexpectedly meet on a crowded train. In response to Williams’ question of where she has been, Esther sharply retorts that she has been looking after his son. She appears to have little regard for what conclusions those around her might draw about her son’s illegitimacy.

This opposes the usual ‘fallen woman’ narrative of maternal melodrama in which the mother loses her self-respect due to her disgrace. In fact, Esther is posited as a ‘New Woman’ not just in the decisions she makes, but the way she is honest about her sexual desires. (For more on the novel’s presentation of Esther Waters as New Woman rather than Fallen Woman, see Dr Andrzej Diniejko’s article on the Victorian Web: http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/mooreg/estherwaters.html) Esther’s  answer to Fred’s proposal is that she is not just a ‘soul’ to be saved, but a woman too. Choosing to marry William is therefore not masochistic self-sacrifice, since her son could have Fred as a father. Also, in opposition to other ‘fallen woman’ narratives, while Esther suffers to a fair extent, she finds happy employment (back at Woodview) at the film’s end and is the proud mother to a now grown up sailor son.

answer to Fred’s proposal is that she is not just a ‘soul’ to be saved, but a woman too. Choosing to marry William is therefore not masochistic self-sacrifice, since her son could have Fred as a father. Also, in opposition to other ‘fallen woman’ narratives, while Esther suffers to a fair extent, she finds happy employment (back at Woodview) at the film’s end and is the proud mother to a now grown up sailor son.

We also commented a little on the matte r of class in relation to the actor playing Esther – Kathleen Ryan. Esther’s kitchen maid job clearly signals that Esther belongs to the working classes. We were a little bemused by Esther’s often genteel quality – though we might perhaps connect this to her religion. This was especially in relation to her accent, which at times had an Irish lilt (like Ryan’s own) and in any case was not signally working class. We noted that this was also the case in other British films from the time.

r of class in relation to the actor playing Esther – Kathleen Ryan. Esther’s kitchen maid job clearly signals that Esther belongs to the working classes. We were a little bemused by Esther’s often genteel quality – though we might perhaps connect this to her religion. This was especially in relation to her accent, which at times had an Irish lilt (like Ryan’s own) and in any case was not signally working class. We noted that this was also the case in other British films from the time.

Given this term’s focus on Dirk, we also discussed his character at length. While some thought William an irredeemable cad, scoundrel and bounder, others were more sympathetic. His back story explains that the family was previously important in the county and gives him this reason to better himself. His ambitions are to go into bookmaking, partially because he insists that his nickname is ‘Lucky’ Latch. This assertion, made to Esther on the hillside, is immediately undercut, however. We hear thunderclaps and a storm commences – predicting that in fact William will not enjoy good fortune.

Given this term’s focus on Dirk, we also discussed his character at length. While some thought William an irredeemable cad, scoundrel and bounder, others were more sympathetic. His back story explains that the family was previously important in the county and gives him this reason to better himself. His ambitions are to go into bookmaking, partially because he insists that his nickname is ‘Lucky’ Latch. This assertion, made to Esther on the hillside, is immediately undercut, however. We hear thunderclaps and a storm commences – predicting that in fact William will not enjoy good fortune.

We also spent some time  discussing how William’s actions comment on his character. William and Esther’s relationship seems to be based on mutual attraction. They enjoy spending time together, and he only pursues another woman once Esther regrets their intimacy and avoids him. His departure from the house is involuntary, and he is at the time unaware of Esther’s pregnancy. William is absent for a fair proportion of the narrative, reappearing 6 years later. Despite the length of time that has passed it is clear that William has fond memories of his time at Woodview. The back room of the pub he runs, and invites Esther to visit after they are unexpectedly reunited, is full of photographs of him with fellow staff from Woodview. He has also employed one of their former colleagues. William’s sentimental streak is particularly evident in the fact that he has kept the silhouette of himself and Esther, presented to them at the ball many years earlier. He seems genuinely to wish to make amends to Esther, soon proposing and proving to be a good husband and father. He is also demonstrably an honest bookmaker – even getting into a fight with his assistant when William insists they pay customers the money they are owed.

discussing how William’s actions comment on his character. William and Esther’s relationship seems to be based on mutual attraction. They enjoy spending time together, and he only pursues another woman once Esther regrets their intimacy and avoids him. His departure from the house is involuntary, and he is at the time unaware of Esther’s pregnancy. William is absent for a fair proportion of the narrative, reappearing 6 years later. Despite the length of time that has passed it is clear that William has fond memories of his time at Woodview. The back room of the pub he runs, and invites Esther to visit after they are unexpectedly reunited, is full of photographs of him with fellow staff from Woodview. He has also employed one of their former colleagues. William’s sentimental streak is particularly evident in the fact that he has kept the silhouette of himself and Esther, presented to them at the ball many years earlier. He seems genuinely to wish to make amends to Esther, soon proposing and proving to be a good husband and father. He is also demonstrably an honest bookmaker – even getting into a fight with his assistant when William insists they pay customers the money they are owed.

Some especially interesting matters in relation to the film’s gender politics were commented upon. William is dismissed from Woodview because of his relationship with the lady of the house’s niece, Peggy. If William were the heroine, it is likely that we would view such a relationship between socially unequal participants as exploitative. Similarly, William is criticised for spending his wife’s money while if the genders were reversed, this might not have been mentioned. Spending a woman’s money is therefore not seen as a particularly manly thing to do – he, after all, should be the provider.

We noted that in some ways William suffers the fallen woman’s fate: he is diagnosed with a lung condition and is granted a deathbed scene. This especially brought to mind the several film versions of Alexandre Dumas’ consumptive La Dame Aux Camelias (1848). Despite William’s illness, Dirk Bogarde is lit well, looking almost pretty, in this scene, further underlining his taking of the place of heroine. It also fits in with the sensitivity of Bogarde – both as described off screen (his star image – as mentioned in his first fan magazine article considered to be different from the character he plays – though as I have noted there is sensitivity there) and progressively onscreen. We can link this to the sexual ambiguity scholars have said that Bogarde embodies. (For example, see Robert Shail’s 2001 article ‘Masculinity and Visual Representation: A Butlerian Approach

We noted that in some ways William suffers the fallen woman’s fate: he is diagnosed with a lung condition and is granted a deathbed scene. This especially brought to mind the several film versions of Alexandre Dumas’ consumptive La Dame Aux Camelias (1848). Despite William’s illness, Dirk Bogarde is lit well, looking almost pretty, in this scene, further underlining his taking of the place of heroine. It also fits in with the sensitivity of Bogarde – both as described off screen (his star image – as mentioned in his first fan magazine article considered to be different from the character he plays – though as I have noted there is sensitivity there) and progressively onscreen. We can link this to the sexual ambiguity scholars have said that Bogarde embodies. (For example, see Robert Shail’s 2001 article ‘Masculinity and Visual Representation: A Butlerian Approach  to Dirk Bogarde’ in the International Journal of Sexuality and Gender Studies, Vol 6, Nos 1/2 and Glyn Davis’ 2008 chapter ‘Trans-Europe Success: Dirk Bogarde’s International Queer Stardom’ in Robin Griffiths’ edited study Queer Cinema in Europe.) It is difficult to know how much this may be related to the fact Dirk Bogarde is the male star – whether it was tailored to fit him as an introduction, or if this would have happened regardless.

to Dirk Bogarde’ in the International Journal of Sexuality and Gender Studies, Vol 6, Nos 1/2 and Glyn Davis’ 2008 chapter ‘Trans-Europe Success: Dirk Bogarde’s International Queer Stardom’ in Robin Griffiths’ edited study Queer Cinema in Europe.) It is difficult to know how much this may be related to the fact Dirk Bogarde is the male star – whether it was tailored to fit him as an introduction, or if this would have happened regardless.

William’s death-bed scene is intercut with scenes from the race on which his, Esther and their son’s futures, depend. Such rhythm is important to melodrama, the lows of slow-moving action contrasting to the highs of unexpected, and at times, unbelievable, action. In the film, activity is especially notable during the scenes of the ball, the bustling crowds attending the races, and especially the derby day scenes. These aspects were especially singled out by reviewers to be of interest to the audience. Trade paper Variety especially commented on these as well as the death bed scene (6th October 1948, p. 11), while fan magazine Film Illustrated Monthly directly contrasted these with the film’s ‘stodgy’ melodrama (November 1948, p. 13). The former even perceptively notes that we are presented with a point-of-view of the race courtesy of William’s ‘imagination’. As such, the film comments not just on the fact that Bogarde is privileged here, since he is granted the heroine’s death, but on cinema itself. While during the setting of the film, the 1870s, cinema was not yet invented, its many predecessors such as magic lanterns were popular. Furthermore, by the date of the film’s production, 1948 audiences were, of course, well used to cinematic devices. For example, we especially noted the effectiveness of William Powell Frith’s ‘Derby Day’ engraving coming to life. The derby scenes also

William’s death-bed scene is intercut with scenes from the race on which his, Esther and their son’s futures, depend. Such rhythm is important to melodrama, the lows of slow-moving action contrasting to the highs of unexpected, and at times, unbelievable, action. In the film, activity is especially notable during the scenes of the ball, the bustling crowds attending the races, and especially the derby day scenes. These aspects were especially singled out by reviewers to be of interest to the audience. Trade paper Variety especially commented on these as well as the death bed scene (6th October 1948, p. 11), while fan magazine Film Illustrated Monthly directly contrasted these with the film’s ‘stodgy’ melodrama (November 1948, p. 13). The former even perceptively notes that we are presented with a point-of-view of the race courtesy of William’s ‘imagination’. As such, the film comments not just on the fact that Bogarde is privileged here, since he is granted the heroine’s death, but on cinema itself. While during the setting of the film, the 1870s, cinema was not yet invented, its many predecessors such as magic lanterns were popular. Furthermore, by the date of the film’s production, 1948 audiences were, of course, well used to cinematic devices. For example, we especially noted the effectiveness of William Powell Frith’s ‘Derby Day’ engraving coming to life. The derby scenes also  connect more specifically to melodrama. Esther bumps into Fred who expresses pleasure, though surprise, that William married Esther. It seems that he expected the melodrama to end differently – as indeed might the film audience.

connect more specifically to melodrama. Esther bumps into Fred who expresses pleasure, though surprise, that William married Esther. It seems that he expected the melodrama to end differently – as indeed might the film audience.

The significance of Derby Day as a social mixer – a ground where those from various classes mingled – was also mentioned. This led to more consideration of the film’s social commentary. We noted that while the film provided an indictment of the class system, it was even-handed in ascribing good and bad characteristics to those from the lower and the upper classes. As already noted, Esther and William are subtly drawn, although it is significant that the most reprehensible of the characters – baby farmer Mrs Spires – is also working class. The upper class Mrs Barfield (Fay Compton) of

The significance of Derby Day as a social mixer – a ground where those from various classes mingled – was also mentioned. This led to more consideration of the film’s social commentary. We noted that while the film provided an indictment of the class system, it was even-handed in ascribing good and bad characteristics to those from the lower and the upper classes. As already noted, Esther and William are subtly drawn, although it is significant that the most reprehensible of the characters – baby farmer Mrs Spires – is also working class. The upper class Mrs Barfield (Fay Compton) of  Woodview is very sympathetic, although the same cannot be said of some of Esther’s other employers. It is more often the institutions, or lack of them, which are criticised. Esther’s illiteracy reflects on the lack of educational establishments, and the scenes of her in the workhouse just after she has given birth underlines her impersonal treatment.

Woodview is very sympathetic, although the same cannot be said of some of Esther’s other employers. It is more often the institutions, or lack of them, which are criticised. Esther’s illiteracy reflects on the lack of educational establishments, and the scenes of her in the workhouse just after she has given birth underlines her impersonal treatment.

Much of this stems from Moore’s novel. The film understandably, however, elides some events. In the novel, Esther returns to her mother and violent step-father’s in London and her mother later dies. In the film, Esther visits London and is shocked to learn the news of her mother’s death. The number of Esther’s employers and the suffering she goes through is also telescoped in the film. This is effectively shown by a montage of Esther engaged in drudgery at different houses, as the years are flashed up on screen. Significantly this is prefigured by the title page of a book on ‘household hints’ and accompanied by narration as to how servants should be treated. This etiquette includes only conversing with servants when necessary, or to pass a greeting. The light tone might be thought to detract from the film’s social message, but it effectively reveals the disparity between the onscreen reality (Esther’s drudgery) and the omniscient, distant, advice-giver who thinks such advice serves Esther’s, and society’s, best interests.

Much of this stems from Moore’s novel. The film understandably, however, elides some events. In the novel, Esther returns to her mother and violent step-father’s in London and her mother later dies. In the film, Esther visits London and is shocked to learn the news of her mother’s death. The number of Esther’s employers and the suffering she goes through is also telescoped in the film. This is effectively shown by a montage of Esther engaged in drudgery at different houses, as the years are flashed up on screen. Significantly this is prefigured by the title page of a book on ‘household hints’ and accompanied by narration as to how servants should be treated. This etiquette includes only conversing with servants when necessary, or to pass a greeting. The light tone might be thought to detract from the film’s social message, but it effectively reveals the disparity between the onscreen reality (Esther’s drudgery) and the omniscient, distant, advice-giver who thinks such advice serves Esther’s, and society’s, best interests.

While some of these omission s are no doubt partly for space, it is also notable that this results in the character of William playing a relatively larger part. Furthermore, we must consider what aspects the film was allowed to show – in terms both of what it was thought audiences would tolerate and official censorship. Anthony Slide has briefly written about the treatment of the film by US censors. The process apparently began early, with the novel sent to Joseph I Breen. Breen suggested that certain elements of the novel (sexual references including seduction, adultery and passionate kisses as well as Esther’s employment as a wet nurse) had to be removed, while others (the suggestion that the Spires would be punished by the law) should be added, and the moral consequences for Esther retained (‘Banned in the USA’: British Films in the United State and their Censorship, 1933-1960 (1998, pp. 61-2). Slide notes that the film was eventually given a certificate on the 28th of July 1949 and released in 1951. Tellingly this was under the title The Sin of Esther Waters. No doubt this, raised incorrect expectations in US audiences, erasing the nuance present in the film’s depictions that are discussion uncovered.

s are no doubt partly for space, it is also notable that this results in the character of William playing a relatively larger part. Furthermore, we must consider what aspects the film was allowed to show – in terms both of what it was thought audiences would tolerate and official censorship. Anthony Slide has briefly written about the treatment of the film by US censors. The process apparently began early, with the novel sent to Joseph I Breen. Breen suggested that certain elements of the novel (sexual references including seduction, adultery and passionate kisses as well as Esther’s employment as a wet nurse) had to be removed, while others (the suggestion that the Spires would be punished by the law) should be added, and the moral consequences for Esther retained (‘Banned in the USA’: British Films in the United State and their Censorship, 1933-1960 (1998, pp. 61-2). Slide notes that the film was eventually given a certificate on the 28th of July 1949 and released in 1951. Tellingly this was under the title The Sin of Esther Waters. No doubt this, raised incorrect expectations in US audiences, erasing the nuance present in the film’s depictions that are discussion uncovered.

As ever, do log in to comment or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk to add your thoughts.