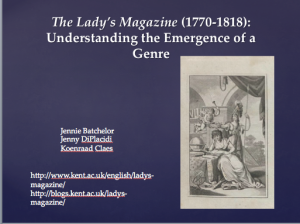

As Jennie Batchelor has discussed earlier, now that we are six months into our project we are excited about going on the road with our research findings, to exchange thoughts about the Lady’s Magazine with you in person. Individually and sometimes with the three of us together, we have presented and will be presenting papers at conferences and seminars in the UK, US, Canada and Belgium, and we also have a few invited talks to look forward to. The breadth of our combined research interests allows us to do justice to the great diversity of the contents of the Lady’s Magazine, and perhaps to surprise you with the wide array of subjects and authors associated with this periodical.

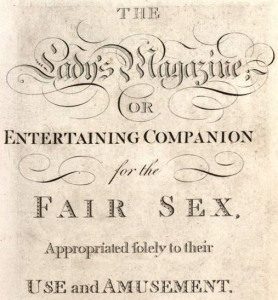

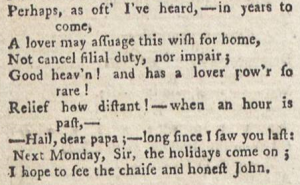

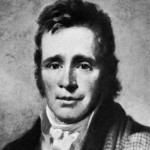

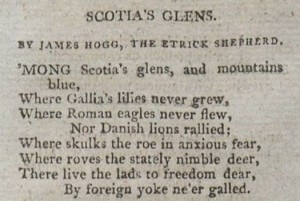

I will for instance attend the upcoming conference James Hogg and His World, which will take place at the University of Toronto from 9 to 12 April. As part of a highly promising panel on ‘Hogg’s Literary Networks and the Periodical Press’, I will discuss the reception of this Scottish Romantic author in the Lady’s Magazine. Nowadays Hogg (1770-1835) is mainly known as the author of the novel The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824), but during his lifetime he was famous for his shorter tales, poems and song collections with a strong focus on his native region of the Scottish Borders, and he was often considered a lesser, coarser and markedly more Tory successor to Robert Burns. Those of you who are familiar with the self-styled “Ettrick Shepherd” may find it odd that his sometimes controversial work was deemed conducive to ‘the Use and Amusement of the Fair Sex’ that the Lady’s Magazine extolled on its title page, but nevertheless it did republish some of his writings. These republications reflect the looseness of copy right law in early-nineteenth-century Britain, and occur in two forms that are both commonly found in periodicals at the time. The Lady’s Magazine featured two poems taken from recently published collections without remuneration for the poet, and, a trick copied from contemporaneous review periodicals such as the Edinburgh and the Quarterly Review, several copious excerpts from Hogg’s tales that flesh out reviews of the books that these came from.

I will for instance attend the upcoming conference James Hogg and His World, which will take place at the University of Toronto from 9 to 12 April. As part of a highly promising panel on ‘Hogg’s Literary Networks and the Periodical Press’, I will discuss the reception of this Scottish Romantic author in the Lady’s Magazine. Nowadays Hogg (1770-1835) is mainly known as the author of the novel The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824), but during his lifetime he was famous for his shorter tales, poems and song collections with a strong focus on his native region of the Scottish Borders, and he was often considered a lesser, coarser and markedly more Tory successor to Robert Burns. Those of you who are familiar with the self-styled “Ettrick Shepherd” may find it odd that his sometimes controversial work was deemed conducive to ‘the Use and Amusement of the Fair Sex’ that the Lady’s Magazine extolled on its title page, but nevertheless it did republish some of his writings. These republications reflect the looseness of copy right law in early-nineteenth-century Britain, and occur in two forms that are both commonly found in periodicals at the time. The Lady’s Magazine featured two poems taken from recently published collections without remuneration for the poet, and, a trick copied from contemporaneous review periodicals such as the Edinburgh and the Quarterly Review, several copious excerpts from Hogg’s tales that flesh out reviews of the books that these came from.

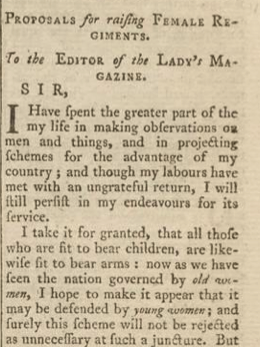

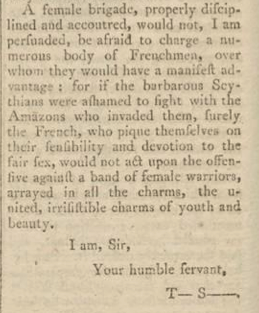

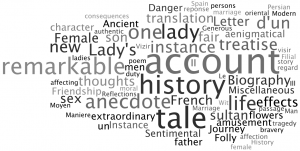

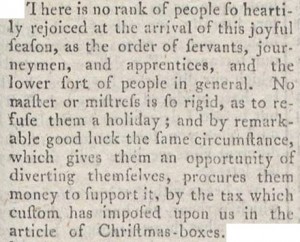

LM, XXXIX (1808). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

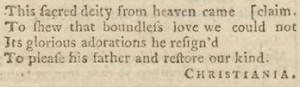

I will demonstrate that these reviews are representative for Hogg’s ambiguous reception, and that they betray attitudes towards Scottish literature in general that are typical of English periodicals of that period. On the one hand Scottish history and literature were somewhat fashionable due to the huge success of the poetry and later on the novels of Walter Scott, but on the other hand a focus on ‘North-British’ culture ran the risk of being dismissed as of too local interest, merely ‘a reflection of the things around’ the author, as one review has it of Hogg’s Shepherd’s Calendar (LM, X new series [March 1829], p. 152). As I will discuss, it is not a coincidence that one of the two poems by Hogg that the magazine republished, in August 1808, explicitly pledges Scottish fealty to the United Kingdom in the ongoing Napoleonic Wars. Amateur reader-contributors in the magazine add to the interpretative context of the magazine by providing in their own submissions satirical and critical comments on exactly the kind of work that Hogg and his Scottish peers were known for.

The Lady’s Magazine was one of the most commercially successful publications of its time, and attracted a readership of both sexes, all ages, and of a large geographical and social diversity. It therefore inevitably played a role in shaping the ‘World’ that Hogg’s work functioned in, and by zooming in on the interpretative context formed by the magazine and on the aspects of his work that were singled out for praise and republication, I hope to shed light on an as yet unresearched aspect of his contemporaneous reception.

—

The Kent Lady’s Magazine Project is not a rock band, but it does have a tour schedule. Here is an overview of where you can find us in the next six months. We hope to meet you at one of these wonderful events!

Jennie Batchelor: conf. ASECS 2015; Los Angeles (19-22 March 2015)

Koenraad Claes: conf. James Hogg and His World; University of Toronto (9-12 April 2015)

Jennie Batchelor, Jenny DiPlacidi, Koenraad Claes: talk ‘A window on the world: the phenomenon of the Lady’s Magazine (1770-1818)’; Chawton House (26 May 2015)

Jennie Batchelor, Jenny DiPlacidi, Koenraad Claes: conf. BARS 2015, Romantic Imprints; Cardiff University (16-19 July)

Jennie Batchelor, Jenny DiPlacidi, Koenraad Claes: workshop ‘Researching Nineteenth-Century Periodicals: Text and Context’, Ghent University (October 2015 – by invitation only)