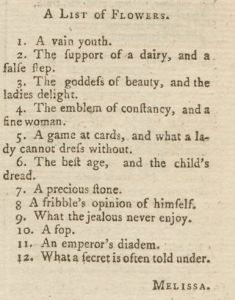

Periodical publications, and especially the subgenre of the magazine, are seldom a one-way street. The content they provide readers with may stimulate response in the form of letters to the editor and other unsolicited copy, and many periodicals turn this reciprocity to good use. As previous blog posts have shown, the Lady’s Magazine was particularly welcoming to the writings of its readership, developing it into a community of reader-contributors who used the magazine as a platform to express their thoughts and feelings, and sometimes to engage with each other. They did this in opinion pieces, (overly) serious poetry, prose fiction and philosophical essays, but there was also room for more light-hearted contributions. There are for instance entertaining puzzles in almost every issue. These come in several closely related forms, such as “charades”, being playful descriptions of a person or object (often in verse); “enigmatical lists” that provide clues to a number of hidden concepts from within an indicated category; and traditional word riddles like anagrams and rebuses. All were meant as a challenge to other readers, who would submit their solutions to be printed in the following number.

LM, VI (1775). Image © Adam Matthew Digial / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

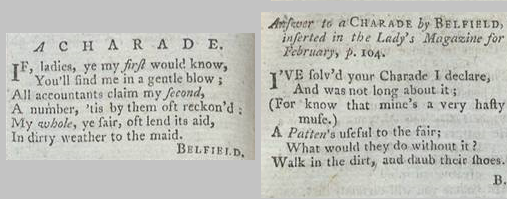

The popularity of the Lady’s Magazine made it a frequent reference in secondary sources, and we can gain insight into how readers enjoyed their puzzles from such contemporaneous accounts. Henry Mackenzie’s essay periodical the Lounger features a seriocomic account of a clergyman who complains that “a young lady […] tried [him] with the enigmas of the Lady’s Magazine, and declared [him] impracticably dull”.[1] Another reverend personage, in the similar publication the Looker-on, objects to “persons, who are called ingenious gentlemen, who have in general no other claim to this title than what is derived from the solution of an enigma in the Lady’s Magazine”.[2] That both puzzles and solutions were regularly published with signature already implies that, even with these less consequential items, there was a sense of achievement if one’s ruminations made it into print. This is not surprising, as devising and solving such riddles allowed for the demonstration of the contributor’s quick intelligence and sense of humour, united in the then highy valued qualification for social life, “wit”. The solutions often contain comments on the originality or intricacy of the puzzle replied to, and certain contributors appear to develop a fondness for each other, repeatedly responding cordially to one another’s submissions.

LM, XXI (1790). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

The puzzles are often still amusing today, and give us an idea of the kind of entertainment that the public sought to derive from print media. Because biographical information on reader-contributors is very scarce, they are furthermore useful for finding out more about the demographics of the magazine’s readership. Not only do readers who seem to know each other outside the magazine sometimes divulge information about their correspondents, but the often highly specific topics of the riddles can also suggest research leads. For instance, the but limited local interest of the “Enigmatical list of Young Ladies of Aldborough in Yorkshire” (August 1784) may help to identify its otherwise mysterious contributor signed “G. Dixon”. When the unknown quantity “R. Beaumont” replies to the long “Enigmatical list of Aldermen in the City of London”, submitted by one “J. Randolph” (March/April 1790), this would suggest some acquaintance with (or at least interest in) metropolitan local government for both correspondents. As contributors in this section often contribute material in other genres too, the puzzles can be very helpful when attributing pseudonymous contributions throughout the magazine.

Regrettably, the gallantry of the gentlemen contributors to the Lady’s Magazine was sometimes compromised when a topic for an enigma presented itself. In December 1788, an anonymous lady wrote in to complain that she had found in a previous issue a puzzle that listed “Old Maids in Newark”, and her name, she believed through error, “inserted in the list of that venerable tribe”. She got her revenge by instantly submitting a list of no less than thirty bachelors in her Nottinghamshire home. From then onwards, editorial statements in the front matter regularly advised contributors that similar “lists of old maids” would no longer be printed: “We affront no species of females”.

If you wish to find out whether you would have fared better than the rustic reverend, we recommend that you follow the Lady’s Magazine research project on Twitter, @ladysmagproject. Choice examples of puzzles, and their solutions, are regularly posted there.

Dr Koenraad Claes

School of English, University of Kent

[1] Modestus [John Cleland?]. “Qualifications required in a country clergyman by his patron and his patron’s family”. The Lounger, Vol. 2, Nr. 40 (5 November 1785), pp. 35-39. p.38

[2] Olive-Branch, Rev. Simon [William Roberts]. “Mr. Barnaby, the Churchwarden”. The Looker-on. Vol. 1, Nr. 3 (17 March 1797), pp. 27-42. p. 40