After four months, hundreds of (wo)man hours, lots of friendly support and chat on social media and some innuendo-laden conversations about pricking, pouncing and Mr Darcy, the Great Lady’s Magazine Stitch Off display previewed yesterday. Today the ‘Emma at 200’ exhibition opens at Chawton House Library in the home that belonged to Jane Austen’s brother, Edward Austen (later Knight).

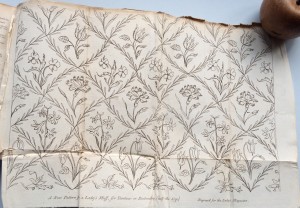

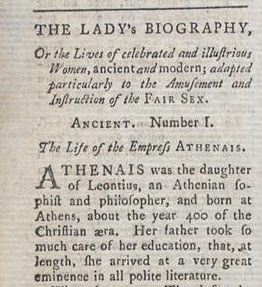

‘Emma at 200: from English Village to Global Appeal’ is a major new international exhibition to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the publication of Jane Austen’s brilliantly witty novel. It is the first major exhibition to be held at the Library since it opened in July 2003 and the result is frankly breathtaking. For the first time, a first edition of Austen’s novel is on display next to the first, rapidly published, French and American editions. Correspondence with Austen’s publisher John Murray is on display, alongside the work of many of Austen’s contemporaries. Early reactions to the novel are represented most spectacularly in the form of Charlotte Bronte’s wonderful (if not entirely complimentary) letter on reading Emma, which is on loan from the Huntington Library in California.

‘Emma at 200: from English Village to Global Appeal’ is a major new international exhibition to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the publication of Jane Austen’s brilliantly witty novel. It is the first major exhibition to be held at the Library since it opened in July 2003 and the result is frankly breathtaking. For the first time, a first edition of Austen’s novel is on display next to the first, rapidly published, French and American editions. Correspondence with Austen’s publisher John Murray is on display, alongside the work of many of Austen’s contemporaries. Early reactions to the novel are represented most spectacularly in the form of Charlotte Bronte’s wonderful (if not entirely complimentary) letter on reading Emma, which is on loan from the Huntington Library in California.

Never before have these items been gathered together in this way. Never again will they all find their way home to Chawton, to a house that Austen knew so well, in rooms in which she spent time. This is a one-off event. If you are within a hundred miles of Chawton in Hampshire, UK, any time between now and 25 September 2016 you have to see this exhibition (visitor information can be found here).

Chawton House Library © Jennie Batchelor

A preview event, for around 35 benefactors of Chawton House Library and the exhibition, took place yesterday, 19 March 2016, on the first day of spring. The crowds of daffodils gracing the lawns either side of the House’s driveway couldn’t quite distract people from how chilly and unspring-like the temperature was. But the atmosphere inside the House, at least, was warm and welcoming.

Joanna Trollope, Patron of Chawton House Library, opening the exhibition © Jennie Batchelor.

Now Chawton puts on a very nice cream tea, I must say, but while the crowds gathered in the kitchen to await the exhibition’s literal unveiling by author, Patron of Chawton House Library, and eloquent champion of historic women’s writing, Joanna Trollope, I snuck upstairs to the Oak Room to set up and pore over the Lady’s Magazine Stitch Off display.

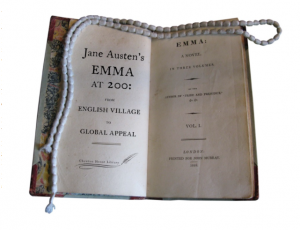

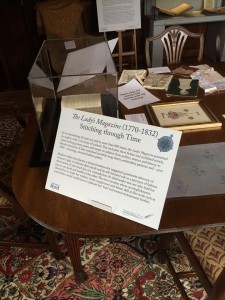

For the duration of the exhibition, the Oak Room (always my favourite room in the house, since I began my own working life there back in 2002) has been given over to the theme of ‘female accomplishments’. At the centre of the room is a large table focusing on the Lady’s Magazine and the work of our Stitch Off participants.

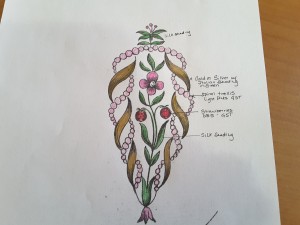

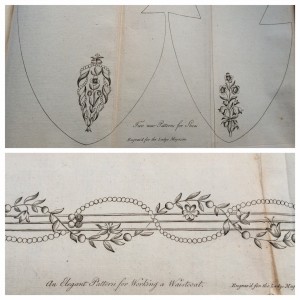

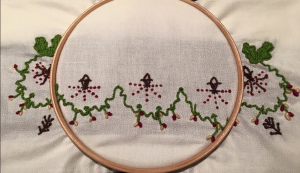

For those of you who haven’t heard of the Great Lady’s Magazine Stitch Off (where on earth have you been, people?) this is a non-competitive needlework project or international sewing bee for which we have made available 10, rare embroidery patterns published in the Lady’s Magazine (1770-1832) – a publication we are pretty sure Jane Austen read and we know Charlotte Bronte read – for people to recreate or reimagine as they wish.

Lucie Whitmore’s 3 pieces for the Stitch Off. Lucie was one of the first people to join the Stitch Off. © Jennie Batchelor.

Our Stitch Off participants have been so generous in sharing work in progress on our Facebook and Twitter feeds over the past few months and I am keeping a log of all of their work in progress in possibly the most gorgeous desktop folder anyone could possibly have. However, not even months of picture filing could prepare me for the complete joy and delight of seeing and handling the actual items themselves.

The Oak Room. Chawton House Library. © Jennie Batchelor.

Staff at Chawton had laid the items and their associated captions out for me on a beautiful wooden table around some exhibition boards I had drafted copy for and an 1811 bound volume of the magazine from the Chawton House Library collection. Everything was wrapped in the original packaging it had arrived in to protect it. Yep: I had the best Christmas morning any 39-year-old has had on a spring afternoon ever. I gently unwrapped everything and started crazily taking and tweeting pictures of all these wonderful items.

Writing desk display featuring left to right: shoe uppers by Alicia Kerfoot; shoes by Nicole Rudoplh; kissing ball by Maggie Gee; and gold work shoe upper by Mary Martin. © Jennie Batchelor.

Every single piece and object was at least 3 times more stunning in reality than in the photos I had seen. I soon realised how much pictures (fabulous though they are for record keeping) distort colours, the size and finish of stitches, the weave and sheen of fabrics, the lustre of beads and gold thread. Mostly of course, pictures also completely distort size. Some items were so much smaller and more delicate than I had imagined them to be. Others were much, much larger. The picture to the left will give some sense of scale.

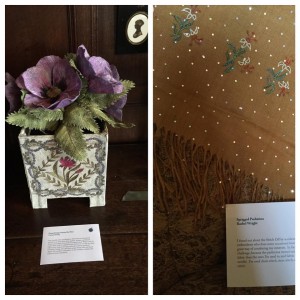

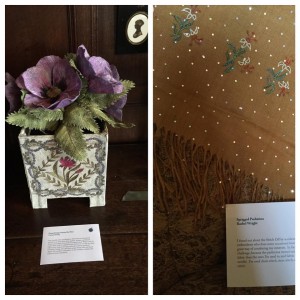

Stitched pot plant by Corinne Young and pashmia by Rachel Wright. © Jennie Batchelor.

I had so much fun arranging the items on various pieces of furniture including: a writing desk adorned with some of the pieces inspired by the 1775 shoe patterns donated by Penny Gore (above); an occasional table on which stands Corinne Young’s stitched plant pot; and an antique armchair, which looks as if it was made solely for Rachel Wright’s pashmina to grace it. But at 3pm I realised I would actually miss the opening of the exhibition if I didn’t step to and run downstairs.

Gillian Dow © Jennie Batchelor.

The exhibition opened with a wonderfully passionate and eloquent speech by Dr Gillian Dow, Executive Director of Chawton House Library, who reminded us that Jane Austen’s most renownedly local novel (structured around those now proverbial ‘three or four families in a country village’) was, from the get-go, a global piece of fiction. It circulated as part of a thriving international print network in which it competed for and won its readers’ attention.

Gillian joked that she had hoped to open the exhibition by breaking a bottle of champagne over an exhibition case in the Great Hall. Much to everyone’s relief Joanna Trollope stepped in instead to do the honours by unveiling the case in a suitably ceremonial gesture. The exhibition goers then moved on to a recital of variations of Robin Adair (a piece of music that will be recognised by readers of Emma) introduced brilliantly and wittily by Professor David Owen Norris.

After that, I dashed back up to the Oak Room ready to welcome exhibition goers to the Stitch Off display and to talk all things needlework and Lady’s Magazine with people once they had made their way through the several other exhibition rooms.

The response to the Stitch Off display was phenomenal. Just phenomenal. I spent a good hour talking to many people about individual items, about the magazine from which the patterns came and reminding people that they can still join in. The room was buzzing with excitement, with people reflecting on childhood experiences of needlework at school, of the embroidery their mothers or grandmothers did, of the desire to get their needles and hoops out of storage and have a go themselves.

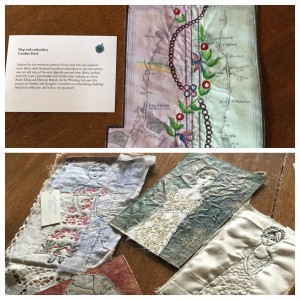

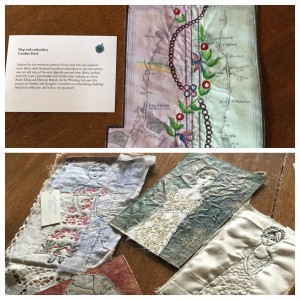

Top: Caroline Hack’s embroidered map. Below: Regency girls by Ruth Zanoni Roskell. © Jennie Batchelor.

Every single item in the display prompted comment and admiration. I mean it. Every. Single. One. The refrains of the room were: ‘stunning’, ‘gorgeous’, ‘beautiful’, ‘so creative’, ‘delicate’ and ‘astounding’. Exhibition goers loved the variety of items on display, from Rachel Whitechurch’s reticule (pictured below) to Maggie Gee’s exquisite kissing ball (pictured above). They loved that the items ranged from faithfully reproduced originals using eighteenth-century techniques, such as Nicole Rudolph’s shoes (pictured above and made from scratch in Colonial Williamsburg), to modern interpretations such as Ruth Zanoni Roskell’s Regency girls and Caroline Hack’s map of nineteenth-century Hampshire overlaid with a 1775 waistcoat pattern.

Sue Jones motif (left); Angela Snape (right). © Jennie Batchelor.

People loved how one design could look so different in different recreations, such as Angela Snape’s and Sue Jones’s equally beautiful but quite different renderings of a motif from a 1796 gown pattern.

Hoop by Bethany Pleydell; handkerchief by Melissa Roberts; ‘Emma’ embroidery by Pamela Buchan. © Jennie Batchelor.

They couldn’t believe that some of our participants were novice stitchers, as Bethany Playdell is. Honestly, Bethany, I’m not sure I believe you either. You are way too good. Other eagle-eyed exhibition goers got very excited when they spotted patterns that weren’t part of our original collection, such as Pamela Buchan’s beautiful embroidery of a pattern from Ackermann’s Repository and Melissa Roberts’ indescribably delicate plain sewn pocket handkerchief (about which Melissa has blogged – see link below – and which was inspired by one of her own Lady’s Magazine patterns).

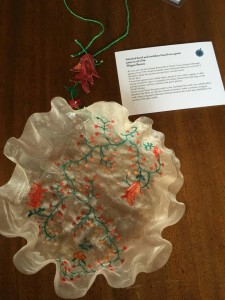

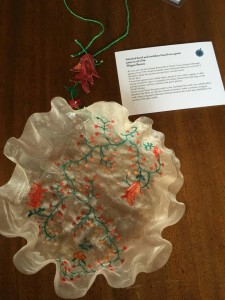

Fabric bowl and textile jewellery by Megan Brown. © Jennie Batchelor.

And then there was the great hand versus machine embroidery conversation. Several of our items are machine embroidered, and one item in particular occasioned a long conversation in which I tried to persuade someone that Megan Brown’s gorgeous fabric bowl was not made by fingers alone. I think I said this three times, but I couldn’t shake the person’s faith. The bowl was so beautiful, so fine, and so precise it just had to be hand embroidered! It is all of those things, but it is not hand embroidered. I promise.

After the exhibition, and after filling a camera and phone full of photos, I made my way home. I had barely seen any of the rest of the exhibition, but I will return and not least because there are new Stitch Off items arriving all the time.

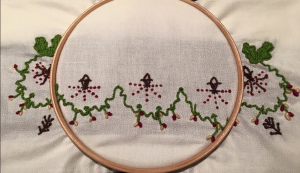

Gentleman’s cravat pattern by Jennie Batchelor. © Jennie Batchelor.

One of the tremendously exciting things about the Stitch Off display is that it is not static and anyone can join us any time between now and the exhibition’s close in September 2016 (see this blog post for details). So if this has sparked your interest, please consider taking part. My own effort – I resurrected embroidery skills unused for 20 years to make up the 1796 gentleman’s cravat pattern – is on display in part to show people that if I can do it, anyone can and should feel free to give it a go.

Crocheted and embroidered reticule by Rachel Whitechurch. © Jennie Batchelor.

A day after the preview, I can honestly say that I have rarely been as proud of anything work-related I have ever been involved in. I have been and continue to be bowled over by everyone’s enthusiasm, support for each others’ work no matter what their approach or medium, whether novice or expert, untrained or trained. In a small way, I like to think that through the project we are replicating the community that the Lady’s Magazine was so successful in creating and which was surely such an important part of its enduring appeal.

Shoe upper by Lucy Dimmock. © Jennie Batchelor

To make that sense of community even more real, some of our lovely Stitch Off participants (like the Lady’s Magazine’s original reader-contributors) are authoring accounts of their own experiences to share with you all. Some of these have been posted on other blogs and there is a link to these posts at the bottom of this one. Please do read them. Other Stitch Off blog posts by our Stitch-Offers, as I affectionately think of you all, will be posted later this week on our blog in an entire week in which we are giving over this site to the Stitch Off. Please read, comment and share as many of the posts as you can.

Finally, I just want to say thank you for making the Stitch Off – the result of a Twitter conversation late one evening – a reality. Whether you have made or are making something for us or cheering on from the sidelines, we appreciate it. This has been an absolutely delight!

Stitch Off blog posts

Maggie Gee’s kissing ball was such a talking point yesterday. You can read the first of Maggie’s multi-part blog post about her experiences here.

The wonderful Alison Larkin was the very first person to pick up the Stitch Off gauntlet and what a job she did for the Captain Cook Memorial Museum where her stunning shawl embroidery is currently being exhibited. You can read about it all here.

Melissa Roberts has blogged about creating her lovely pocket handkerchief based on a 1776 pattern in her own collection is here over at Two Threads Back.

Rachel Wright, who has made the glorious pashmina, has written no less than 3 fantastic posts about her process over at VirtuoSew Adventures. Here is the most recent, but we recommend you read them all.

For information about visiting the ‘Emma at 200’ exhibition at Chawton House Library, please follow this link.

Dr Jennie Batchelor

School of English

University of Kent

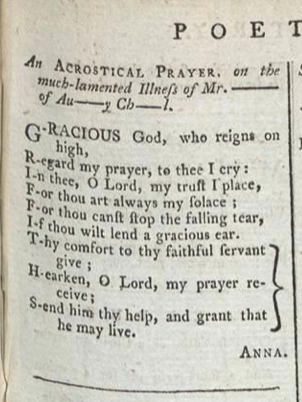

The acrostic poems in the magazine were exploited by the contributors in deliberately revealing ways. Their use is often not merely an attempt to highlight the contributor’s cleverness, but a means of interacting with members of a local geographical community – most often (and this is why I love them) with the object of the writer’s affection. Contributors could give voice to questions, desires, apologies and declarations to those closest to them in their personal lives through the pages of the magazine. The medium of the periodical provided a veil that allowed, in particular, women to voice their desire to men without the danger of being directly observed by a social circle and consequently condemned for forward or coquettish behavior.

The acrostic poems in the magazine were exploited by the contributors in deliberately revealing ways. Their use is often not merely an attempt to highlight the contributor’s cleverness, but a means of interacting with members of a local geographical community – most often (and this is why I love them) with the object of the writer’s affection. Contributors could give voice to questions, desires, apologies and declarations to those closest to them in their personal lives through the pages of the magazine. The medium of the periodical provided a veil that allowed, in particular, women to voice their desire to men without the danger of being directly observed by a social circle and consequently condemned for forward or coquettish behavior.