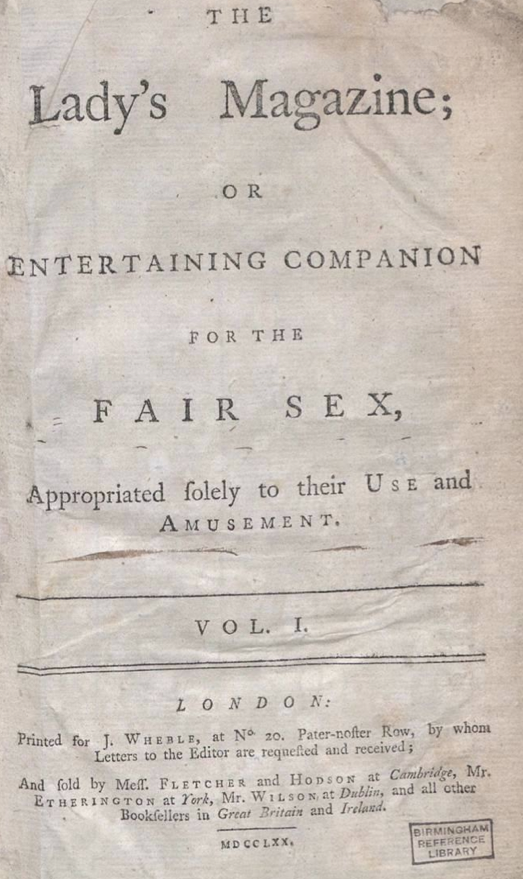

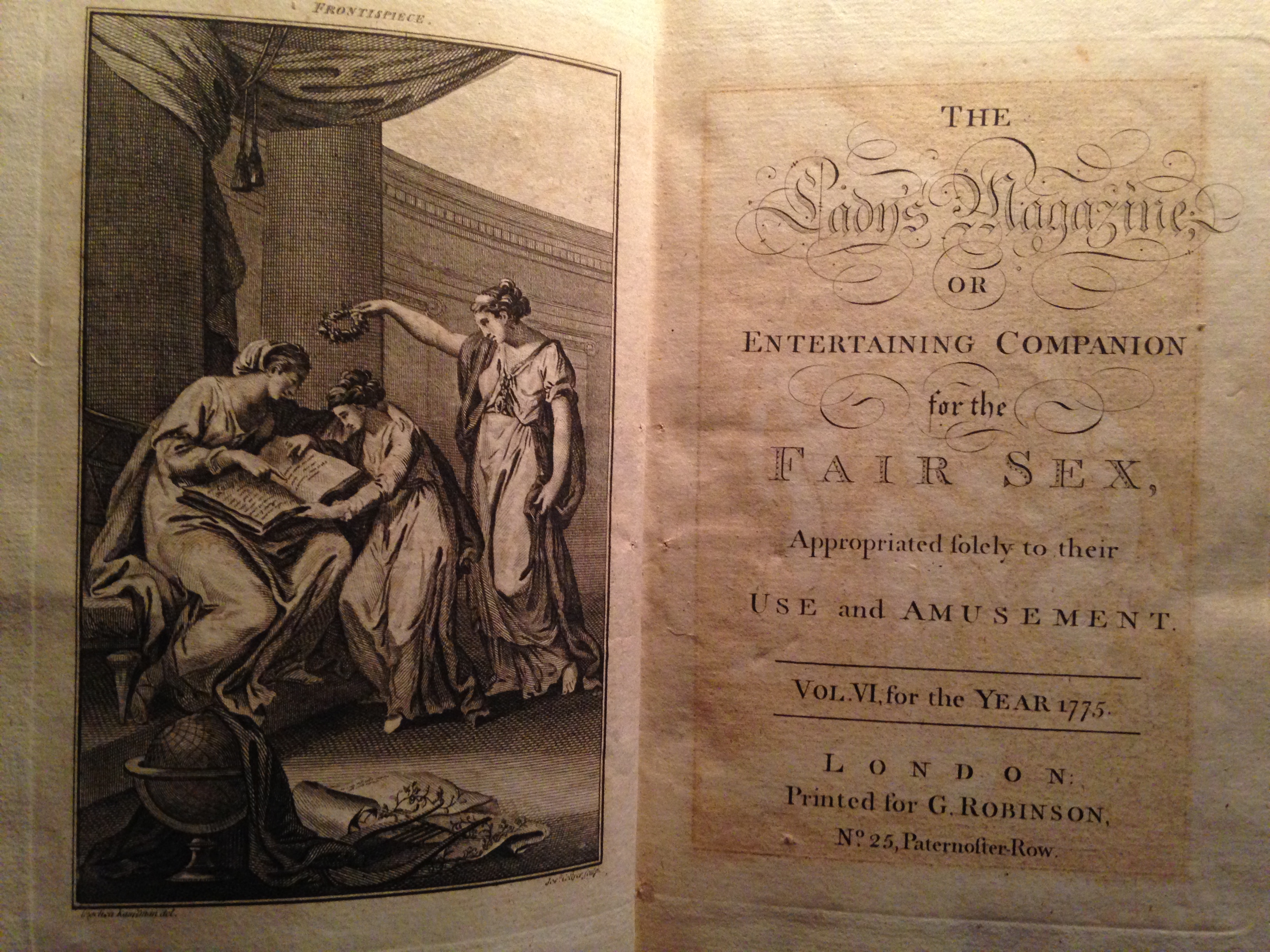

Our research project will generate a range of publications. Aside from our main research output (our annotated index of all of the content of the Lady’s Magazine from 1770-1818), we have this blog of course, and a series of journal articles and book chapters planned or already underway.

I am also engaged in a longer-term project to write a book about the Lady’s Magazine. Its completion is some way off, but it’s had a working title for some time. The bit after the colon in the title changes every couple of months, but the bit in front of the punctuation mark hasn’t changed for some years. Of course, I might reconsider things at the eleventh hour, but for now at least I feel pretty certain I want to give it the main title Guilty and Other Pleasures.

I have so many reasons for wanting to call it this. I want the title to reflect the slight sense of embarrassment I once but less regularly feel when people ask me what I am reading and working on and I say early women’s magazines. I want to rehearse in order to subvert stereotypes of women’s magazines as trivial (trivial because pleasurable) froth. And I want ultimately to make clear that neither I nor the magazine’s original readers really have anything to feel guilty about when reading it. The magazine took itself very seriously. It took its readers’ pleasure very seriously.

Even so, I do sometimes feel my conscience being pricked when reading the magazine. Should work really be such fun?

These feelings are most intense when the magazine manages to combine more than one guilty pleasure at once. For Charlotte Bronte, who wrote in a letter to Hartley Coleridge dated 10 December 1840 of furtively sloping off as a child to read old copies of the Lady’s Magazine instead of minding her lessons, fiction was a guilty pleasure. For me, it’s crime.

Crime fiction – my regular non-work guilty pleasure of choice – is not an established genre in the late eighteenth century, of course, although, novels of the period are full of nefarious deeds (murders, blackmail and so forth). But accounts of true crime were popular in the eighteenth-century press and although the Lady’s Magazine did not indulge such interests as frequently as many other contemporary newspapers and periodicals, when it did so, the result was invariably arresting.

LM I (Feb. 1771). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

For the most part, crime is confined to the back pages of the Lady’s Magazine where the monthly home and foreign news sections appeared. These monthly digests of important events regularly included snippets on thefts, murders, fraud and arson. But sometimes the crime was so noteworthy or shocking that it spilled out of these densely printed, tightly constrained columns to occupy pages of the magazine itself.

Many of the biggest trials of the day were rehearsed in the magazine, often with an accompanying engraving. In April 1776, for instance, the magazine devoted several pages to an account of the Duchess of Kingston’s infamous bigamy trial, or as it subtitled the article: ‘An impartial and circumstantial Detail of the Trial of the Duchess of Kingston’. Nodding to the perceived impropriety of the magazine’s inclusion of the trial, the editors pointed out that since the trial had ‘engrossed the ears of curiosity’, it was their ‘duty to give a summary account of it’ for their readers (LM VII: 171).

LM VII (Apr. 1776): 171. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

But of course, subscriptions and sales must have played a part in such decisions as well as this perhaps spurious sense of duty. Had the magazine not covered the Duchess of Kingston’s trial or that of the Countess of Strathmore and her despicable husband Stoney Bowes (documented in Wendy Moore’s very readable 2009 Wedlock: How Georgian Britain’s Worst Husband Met his Match) or that of Warren Hastings (which the magazine serialised over many months), it would have been out of step with its competitors and missing a commercial trick.

What is so strange about the trial accounts – with their matter of fact style, their lack of sensationalism or the kinds of editorial gloss we expect today – is that they are one of the few aspects of the magazine that remain closed off. One of the most exciting things about reading the Lady’s Magazine, as we have nodded to before, is knowing that the authority of any individual pronouncement or contributor was open to question. Readers could and frequently did exercise a right of reply on all manner of content, from advice on marital infidelity, to views on the behaviour of servants, or wives or children. But not so on criminal cases where the voice of the law was final. The trial verdict was irrefutable and not open to debate.

LM XXI (July 1790). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

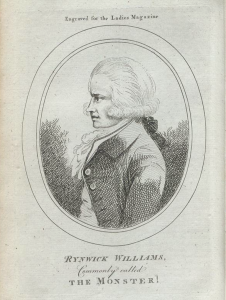

This was true even of the most extraordinary and disturbing of cases. I was reminded of this the other day when flicking through the July 1790 issue of the magazine when I came across this portrait engraving (instead of the the one I was looking for) of Rhynwick (here Rynwick, but also sometimes referred to as Renwick) Williams, commonly known as ‘The Monster’. The monster first came to notoriety in 1788 in the first of a series of incidents in which women were verbally harassed and then their clothes and bodies slashed or stabbed while walking through London.

The phrase media frenzy is an anachronism, but it’s hard to find one that more accurately describes the press’s and public’s reaction to these strange and appalling crimes. There was intense speculation about the Monster’s identity and motives and numerous contemporary engravings were produced of him attacking women in the streets with large knives. You might have seen a version of these events fictionalised in the BBC’s Garrow’s Law (2009) but would be advised, if your interested in similarly sinister things to me, to read the fascinating chapter on the events in Robert Shoemaker’s The London Mob: Violence and Disorder in Eighteenth-Century England (2004). In any case, in June 1790 a trial was successfully brought against Williams after an attack on Anne Porter in St James’s. A summary of the trial in which Williams was found guilty appeared in the July issue of the magazine, the first time the crimes had been documented in it. Williams’s subsequent retrial – there were many reasons not to be convinced by the original prosecution – failed to overturn his conviction but was not reported in the Lady’s.

The story of the Monster – with its pre-Ripper undertones – has fascinated many since it was first reported in the 1780s. But arguably what’s most fascinating about the Lady’s depiction of it is its refusal to accede to the temptation to indulge in sensationalism or prurience when many of its competitors were seizing such opportunities with relish. The engraving it published was of Williams, not of an attack. The events described, while unsettling, are presented in the manner of a brisk trial transcript, not dissimilar to those with which readers of this blog might be familiar from trawling through the records digitised on the indispensable Old Bailey Online.

With crime as with all else, then, there is evidence that the editors of the Lady’s Magazine took their readers’ reading pleasure very seriously so that neither party had anything to be guilty about. And so I for one have decided that I shan’t feel guilty either.

Dr Jennie Batchelor

School of English

University of Kent