Working on The Lady’s Magazine project this May and June has led me down all manner of bizarre eighteenth-century rabbit holes, and no two days are ever the same. I have, over the month, chased one of Mary Robinson’s stray Sylphids across numerous newspapers. I found myself reading about sheep rot in an agricultural magazine just yesterday. I encountered a very serious vicar (J. H. Prince) who, as well as reflections on suicide, also wrote odes on dead cats (there are a surprising number of these, from a surprising number of contributors, in the magazine). I caught a brief glimpse of Emma Hamilton, or someone posing as her, in the pages of 1800, waxing lyrical about reading Dimond’s petrarchal sonnets. I smiled as the same hopeless swain, writing hopeless lines of poetry, tried with his lays first to ensnare one Susan Yates, and then just two months later, a Sophia. I laughed at Dr Hawes’ recommended methods for restoring to life the apparently dead (‘what thou doest – do quickly’), and laughed even more as ‘Tommy Softchin’ bemoaned his lack of whiskers. Sometimes I got very carried away on Ancestry; I tracked down the son of one of the magazine’s long-term contributors, John Webb. Webb often wrote poetry about his sons, and this particular one, Conrade, had a ‘providential escape’ from death by cart in 1800.[1] This escape proved fortunate for him, obviously, but unfortunate for 18 year-old William Riddle, who, 33 years later, was sentenced to two month’s confinement for drunkenly stealing a ham from his master, a cheesemonger: Conrade Manger Webb. Reading the Old Bailey Records, I thought about the ‘playful Conrade’ that a charmed father wrote about, the suing cheesemonger of 1833, and the 77-year-old man who lived and died on Edgware Road, weaving together these three seemingly disparate images, these three traces of a real, lived life.

The paucity of biographical records from this period often sees lives squashed into stubborn, unyielding signifiers. The thrill of finding the right person is quickly overwritten by frustration as that person is reduced to a date of birth, marriage, death, or a street number. Sometimes the records give a bit more: a court appearance, a list of household residents, a photo of a document. But I found over the last few months, that the magazine contributions themselves could sometimes provide rich insights into the lives of the contributors. In other words, they can make the records speak to us.

My work on the project was on attribution and authorship. I donned my best detective hat and ploughed my way through the years, cross-referencing each entry to find out whether it was original; if not, where it came from; and in any case, who might have written it. Tracking down an unacknowledged appropriation has its own pleasures, particularly when the search is a long, piecemeal one, but the most rewarding (and the most potentially frustrating) work lies, I think, in attribution. The magazine is a wonderful, dense, and unruly site in which to perform recovery project archaeology. Although there are so many contributors who will probably never be traced (the Eleanor H**** who translated 6 plays from French and German between 1799 and 1805 proved just one source of frustration for me this month), some are just waiting to be discovered. Likewise, although many contributors had short-lived careers in the Lady’s Magazine, some went on to publish novels or poetry collections after. Others can tell us something about their particular historical moment, about their situated and personal experiences. As Jennie noted in a recent blogpost, recovering the lives of contributors ‘might not seem all that important beyond fleshing out a footnote in literary history. But for [each writer] we find, we are able to bring into slightly sharper focus what it might have meant to be an author in the period covered by the Lady’s Magazine.’[2] Indeed, the aim is to uncover a messy eighteenth-century that is sometimes overlooked in favour of clean, linear narratives. The magazine is the perfect forum for this sort of work: inclusive, democratic, dialogic. And it affords fascinating glimpses into lost lives, which speak to modern concerns as much as they did to the concerns of their many eighteenth- and nineteenth-century readers.

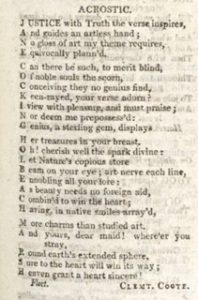

In the spirit of recovery, then, and as a way of making the figures and names ‘speak’, I want to share the story of one of the Lady’s Magazine’s contributors, which takes us all the way from Lincolnshire to Washington. This story resides in the poetry sections of the magazine for 1805, which play host, as they often did, to a transient poetic community. When I first opened up the index, I optimistically scanned the names, looking for partial ones that I might be able to flesh out. One jumped out right away: Jane C—k—g. I searched Ancestry a few times that day with variations, but with no definitive results, and quickly gave up and moved on with the more fruitful business of searching out appropriations. But Jane kept asking for attention. By the time I arrived in 1805, I’d given up on finding her, when one afternoon, I arrived at this acrostic:

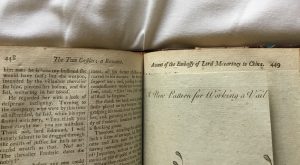

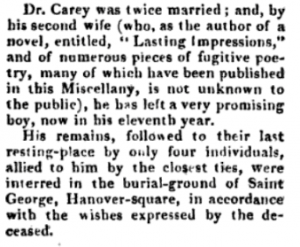

LM 31 (Aug 1800): 439. mage © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

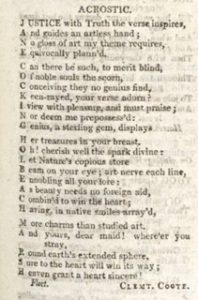

And there she was. Jane Cocking, Holbeach Marsh. Right after an acrostic to her sister Anne Cocking. I had a lead, and Ancestry was forthcoming.

Jane was born in Lincolnshire on 14th June 1789 to William (1760-1820) and Ann (nee Worseley, 1750-1834) Cocking. Her sister, Ann(e) (spelling varies in the records), was four years older than her (b. 7th March 1785). They lived at Holbeach Marsh, a fenland area in the South Holland district of Lincolnshire, which is where Jane signed most of her poetry from.

Jane started her 7-month writing career in the Lady’s Magazine, just shy of 16 years old, with six contributions to April’s poetry section.[3] Two of these were acrostics; one for an unknown woman called Jane Herbbass(?), and the other for her sister’s fiancé, William Blanchard (‘May you e’er live in peace and ease, / Belov’d by her you wish to please’). She also contributed an elegy on the death of her friend, Mary Cooling, who had died in December 1804, aged 15 (‘how transient were her charms’), and she wrote a poem to a Miss. Harrison, (probably Nancy Harrison, b. 31 May, 1783). These four contributions are full of assertions of her subjects’ virtues, and hopes for their future happiness, mostly in terms of marriage, and the successful avoidance of ‘false-hearted swains’ and ‘fickle shepherds’. In one of the other poems, ‘Some verses on leaving H—–N’, Jane laments having to leave friends after a long stay spent reading and writing poetry. She writes, wistfully, ‘ah when I think how our time we were spending – / In composing of poetry, or reading a book – / We were ever obliging, and never offending, / And the smile of good nature appear’d in each look’. The final poem, ‘Verses on a pleasant walk near Lincoln’, bids farewell to the landscape she knows, although at this point, readers are unsure what this means or where she is going:

Farewell, lovely scene! I must go,

And leave thee, ah! leave thee behind!

But I this, as some solace, shall know

Thou wilt e’er have a place in my mind.

Ah! how peaceful I oft have sat down,

Enjoying thy beauties serene!

Undisturb’d by the noise of the town,

I’ve hail’d thee the charmingest scene.

But now I must bid thee adieu,

Tho’ ‘t will certainly give me much pain;

Much more, as I certainly know

I shall ne’er see thy beauties again.

These are clumsy and perhaps derivative poems, but they also tell us the story of a contributor that is wholly relatable to anyone who was once a teenage girl, who tried to imitate what she read, who had heartfelt hopes for her loved ones, or who had to move home as a child.

In ‘on leaving H—–N’, she writes, despite obviously being preoccupied with the upcoming move in her other poems:

My heart is a gay one, a stranger to sorrow: –

That word in my ear has a very harsh sound; –

Present time I employ, and ne’er think of tomorrow –

‘Tis a period, we’re told, ‘that’s no-where to be found.

In July, Jane heeds her own advice, and leaves off thinking about leaving, in order to respond to a poem written by James Murray Lacey. His ‘Lover’s List’[4] establishes him as the Lady’s Magazine’s very own, eighteenth-century version of Lou Bega (see the questionable 1990 hit single Mambo No. 5), cataloguing his adoration of Evelina, then Mary, then Selina, then Betsy, then Nancy, and so on: 32 named women and ‘fifty more’ that he cannot name. Jane’s witty response in July reworks the original poem from a female respective, listing a slightly more modest 10 lovers, and ending with a flirtatious address to the original author: ‘I never will desert this swain [Francis is the one she’s settled on], / I do him love so well; /No, no, I’ll never change again – / Except for J. M. L.[5]

The following month, James Murray Lacey raises young Jane a tongue-in-cheek declaration:

You wrote, – and now she charms no more;

Jane fills each love-devoted thought:

I only fancy’d love before,

But now I’m certain I am caught.

[…]

From Portsmouth lately when I came,

‘Where have you been?’ ask’d all I knew;

My answer ever was the same, –

‘To Holbeach Marsh,’ – a jaunt quite new!’[6]

His request that she ‘turn Francis off’ and write back to him sadly went answered.

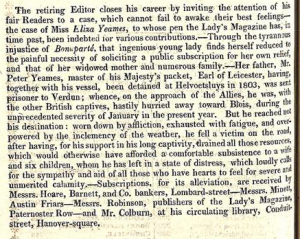

Meanwhile, we find out where Jane is actually going from another contributor, Belinda, who, in June 1805 writes two poems: ‘Lines to Miss Jane C—k—g’ and ‘Lines to the Misses C—k—g, on their going to America.’[7] From Belinda’s other poetry, alongside poems written to her, I was able to establish that her real name was Mary, and she had a sister who was probably called Ann. The final stanza of ‘on their going to America’ is intriguing. Belinda writes: ‘‘Tis a prayer that proceeds from the heart, / Although by a stranger ‘tis penned: / With regret she will hear you depart; / Then what pangs ‘twill inflict on each friend!’ Whilst these lines suggest that was wasn’t known to Jane personally, Jane’s response suggests that they were actually close friends. This is perhaps then demonstrative of the ways in which, like modern internet forums, the Lady’s Magazine provided a space in which to make ‘virtual’ friends. More likely, I think, given that Belinda writes from Fleet, near where Jane lived, it demonstrates the writer’s dogged adherence to the pseudonymity of the poem. Whilst Mary knows Jane, Belinda does not.

Jane’s poetry dominated the section in April, and then in October, although the poems included in October’s issue were written between May and August. From Holbeach Marsh, she writes praising Belinda (Mary). She also writes a short poem on contentment; one on modesty, addressed to a Mr. W—ley; one entitled ‘The Forsaken Swain’; and an acrostic to Clement Coote, who had written acrostics to Jane and Anne in the magazine two months before.[8]

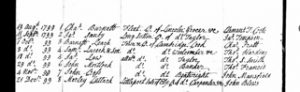

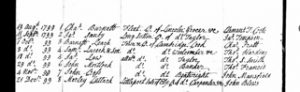

Coote, if he is the Clement Tubbs Coote that I tracked down, was christened in November 1784 in Cambridge, and so would have been close in age to Anne Cocking. In 1799, aged around 15, he was apprenticed to Charles Burnett, a grocer, in Fleet, Lincoln.

Clement T. Coote is apprenticed to Charles Burnett, grocer. Aug 1799.

He signs his 1805 poems from Fleet, as Belinda does, suggesting that this is how he knew Anne and Jane (Fleet is about 8 miles from Holbeach). In 1807, Coote returned to Cambridge, apparently giving up poetry, to take up another apprenticeship.

Clement Coote is apprenticed to William Cockett, draper. Dec 1807.

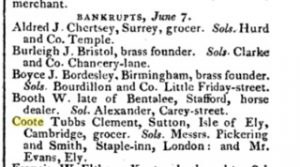

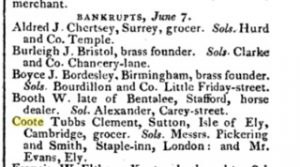

In 1809, he married Mary Cole, who I spent an inordinately long amount of time trying to prove was Belinda in the hopes of a nice tidy circle, but alas, no such luck. He went on to run a business as a draper, grocer and tallow-chaundler, but unfortunately went bankrupt in 1817.

Clement Tubbs Coote goes bankrupt. Literary Panorama and National Register 6 (Aug 1817)

At some point shortly after this, the Coote family moved to America too, arriving in Philadelphia. Clement Coote died in Baltimore in 1849.[9]

But back to Jane. By August 22nd 1805, Jane was in London, where she penned a farewell poem to Clement Coote, wishing her ‘dear Mr C—’ health, wealth and contentment.[10] Did she see him when he arrived on American shores 12 years later? Jane also wrote a final goodbye poem to Belinda (Mary), and to ‘Albion’s happy isle’ before she ‘brave[d] th’Atlantic deep’.[11] In this latter poem, she writes touchingly of storing memories of the English countryside – singing blackbirds and linnets – anticipating that in her new home, ‘Remembrance then will force the tear to flow, / When in my fancy I behold each spot, / Each fav’rite spot, I formerly admir’d.’ But she goes on:

‘But what are these? mean trifles, when compar’d

With leaving friends, friends much esteem’d, behind:

Whene’er I think on that, it casts a damp –

A cheerless damp throughout my frame I feel.

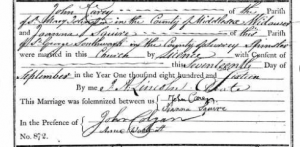

‘Cheerless damp’ is the same phrase that Belinda uses in her 1806 poem ‘To a friend leaving the country.’[12] On September 12th 1805, Jane’s sister Anne married William Blanchard at St George in the East, in London. Then sometime over the next few weeks, Jane’s parents, Jane, and the newly married Anne and William all emigrated to America, where they settled in Washington, in the District of Columbia.

The Cockings emigrated at a time which saw a lull in the numbers of arrivals to America, mostly due to the Napoleonic wars.[13] Maldwyn Allen Jones suggests that the total number of immigrants from Europe to America 1783-1815 was about 250,000, but with only about 3,000 a year during the Napoleonic wars.[14] So what made them leave, enduring at best, an uncomfortable, and at worst, a deadly journey across the Atlantic? Belinda’s fears for her friend undergoing a dangerous journey are apparent in the lines:

Atlantic, be proud of thy charge!

Neptune, curb ev’ry boist’rous storm!

With honour thy duties discharge;

Let nought thy smooth bosom deform![15]

And indeed, shipwrecks were a real threat. A list of all the shipwrecks in 1806, which is in the hundreds, can be found here. Unless I can track down Jane writing in America, it is unlikely that we will ever know what her journey was like or why her family travelled 3,000 miles to start again in Washington. However, they arrived safely. Life went on.

On August 19th 1813, aged 24, Jane married an American called Charles Carroll Glover. They remained in Washington, appearing on the 1820 federal census with three children and – something that shocked me, and that might tell us a bit more about the Cockings’ economic status – two young female slaves. Suddenly the weaving of strands that I already thought I knew became harder; the coherent, imagined, and celebratory picture I’d created was fragmented. Jane’s sister Anne (now Blanchard) also remained in Washington, had a large family of six(?) children, and owned at least one slave in 1830. Around this time, the number of slaves in Washington had reached its peak, representing twelve percent of the city’s population.[16] Anne shows up in 1862 claiming compensation for two recently freed slaves, Rachel Jackson and William Henry Taylor.[17] You can view her petition here.

Jane was widowed in 1827, and outlived all of her children too: her daughter Adeline died at 9 months; and sons William at 21, and Richard at 29. Jane herself lived to the grand age of 87, dying on September 14th, 1876.

Gravestones at Oak Hill Cemetery, Washington, District of Columbia. From left to right: Charles and Jane Glover; Charles and Jane Glover’s children; Anne Cocking (Blanchard).

Back in 1805, Clement Coote wrote a poem for Jane, ‘on her Arrival in London, just before her Departure for America’, but this wasn’t published until April 1806.[18] In it, he hopes: ‘May you upon Columbia’s plain / Find some who love the tuneful train’, and wishes that she will continue to be inspired by other poets to write. Whether she did or not remains to be seen, and checking some American periodicals for Jane Cockings or Jane Glovers is on the to do list.

Tracing Jane C—k—g did several things for me. It demonstrated the way in which the Lady’s Magazine functioned as a forum for communication between momentary, geographically-located, networks of friends. It gave me an insight into the materials available for a teenage girl to express her joys and her anxieties, her love of the countryside she grew up in, and her fears about leaving it for America. It suggested, in linking a village in Lincolnshire to the changing legal status of slaves in mid nineteenth-century America, that the magazine’s webs and networks can be extended to cover a huge variety of geographical spaces and historical issues, of which migration and globalisation formed an integral part. This month has been a profoundly odd one, but also a profoundly human one, in which the connections between the past and the present have at once been fractured – sheep rot seems inescapably alien to me, writing in 21st century London – but also maintained. We continue, as people, to be fragmented across our daily lives, our writing, the records we leave, even the thoughts we have. Reading Jane – at once anxious, sorrowful, optimistic, virtuous, flirtatious; a child writing juvenilia and a slave owner; an intrepid teenage voyager and a widowed mother – was a palpable reminder of this.

Dr Kim Simpson

School of English

University of Kent

Notes

[1] LM 31 (Dec 1800): 672

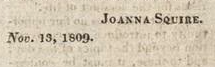

[2] Jennie Batchelor, ‘Our ‘ingenious correspondent’: Finding Joanna Squire’, https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/ladys-magazine/2016/06/06/our-ingenious-correspondent-finding-joanna-squire/

[3] LM 36 (Apr 1805): 214-16

[4] LM 36 (Feb 1805): 103

[5] LM 36 (Jul 1805): 381

[6] LM 36 (Aug 1805): 437

[7] LM 36 (Jun 1805): 327

[8] LM 36 (Oct 1805): 549-51

[9] There is more information about Clement Coote, including a photograph of his portrait, here: http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=113760171&ref=acom

[10] LM 36 (Oct 1805): 551

[11] LM 36 (Oct 1805): 550

[12] LM 37 (May 1806): 275

[13] John Powell, Encyclopedia of North American Immigration (New York: Facts on File Inc., 2005), 37

[14] Maldwyn Allen Jones, American Immigration, 2nd edn. (London: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 54

[15] ‘Lines to the Misses C––k––g, on their going to America’. LM 36 (Jun 1805): 327

[16] http://civilwardc.org/texts/petitions/about

[17] ‘In December 1861, Senator Wilson submitted a bill proposing the immediate and compulsory emancipation of the District of Columbia’s 3,300 slaves through a program of federal compensation. The District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act, which President Lincoln signed on April 16, 1862, allotted an average of $300 per slave to all slaveowners who were loyal to the Union, for a total payment of $900,000. Under the Compensated Emancipation Act, all slaves in the District of Columbia were free immediately. Slaveowners had ninety days to submit a petition, which consisted of a preprinted form, requesting compensation for their slaves. The petitions, which were written by the slaveowners, identified each slave, provided a personal description, including the slave’s “age, size, complexion, health and qualifications,” and presented an estimated value of the slave for purposes of compensation. […] During the three-month process, 966 slaveowners filed petitions and testified before the commission.’ http://civilwardc.org/texts/petitions/about

[18] LM 37 (Apr 1806): 217

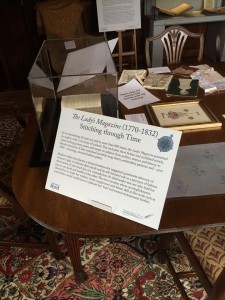

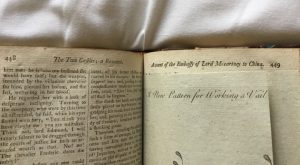

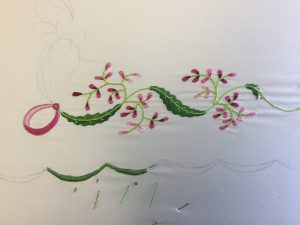

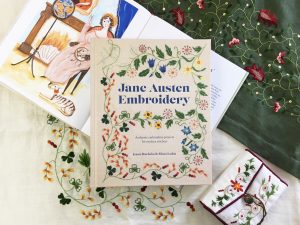

When I posted pictures of the patterns on Twitter, I had absolutely no idea that they would have the impact that they did. People loved them and I loved telling them what I could about them from my research over the years. But I also knew I had a lot to learn, too, and boy did I learn a lot when I released the patterns online so people could start making and adapting them for themselves.

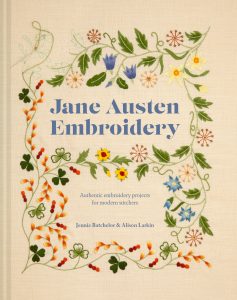

When I posted pictures of the patterns on Twitter, I had absolutely no idea that they would have the impact that they did. People loved them and I loved telling them what I could about them from my research over the years. But I also knew I had a lot to learn, too, and boy did I learn a lot when I released the patterns online so people could start making and adapting them for themselves. And then, I got an invitation from one of the first people to get involved in the #StitchOff, Alison Larkin, to speak at the Yorkshire and Humberside Embroiderer’s Guild. I did a talk on the needlework from Jane Austen’s day – after all, we know she read the Lady’s Magazine – to the #StitchOff, proudly showing off the work of the Stitch-Offers along the way. Alison bought several pieces that she worked up for the Stitch Off for display, one created while working at the Captain Cook Memorial Museum in Whitby.

And then, I got an invitation from one of the first people to get involved in the #StitchOff, Alison Larkin, to speak at the Yorkshire and Humberside Embroiderer’s Guild. I did a talk on the needlework from Jane Austen’s day – after all, we know she read the Lady’s Magazine – to the #StitchOff, proudly showing off the work of the Stitch-Offers along the way. Alison bought several pieces that she worked up for the Stitch Off for display, one created while working at the Captain Cook Memorial Museum in Whitby. introduction to embroidery in Jane Austen’s Britain and has separate features by me on embroidered dress, accessories and household objects, full of references to novels by Jane Austen and her contemporaries. The practical section of the book has 15 projects based on Lady’s Magazine patterns graded for all ability levels and with full instructions devised by Alison. Some of the patterns will be familiar to those who joined in with the original #StitchOff, albeit in new interpretations. Many you won’t have seen before! And the book is just gorgeous, with beautiful illustrations by Polly Fern, and photography by Penny Wincer.

introduction to embroidery in Jane Austen’s Britain and has separate features by me on embroidered dress, accessories and household objects, full of references to novels by Jane Austen and her contemporaries. The practical section of the book has 15 projects based on Lady’s Magazine patterns graded for all ability levels and with full instructions devised by Alison. Some of the patterns will be familiar to those who joined in with the original #StitchOff, albeit in new interpretations. Many you won’t have seen before! And the book is just gorgeous, with beautiful illustrations by Polly Fern, and photography by Penny Wincer.