LM XII (Jan 1781): iii. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

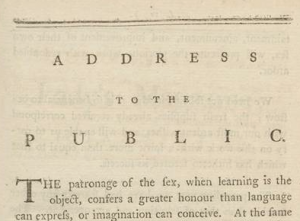

We couldn’t let the first month of the year come and go without reflecting on one of the constants throughout Lady’s Magazine‘s long print run. Every January from the early 1770s right through 1818, where our project ends, the magazine opened with an Address to the Public. The column’s title sounds rather grander than the editorial leader familiar from today’s monthlies, although its function was largely identical: to thank readers for their patronage in buying the magazine; to divert them to content of which the editors were especially proud; and to persuade subscribers that their money had been well spent.

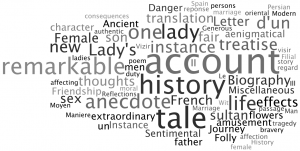

The sheer quantity of puffing that takes place in the Addresses to the Public is more than enough to power any one of the many ‘aerostatic voyages’ (balloon flights to you and I) about which the Lady’s Magazine routinely raged. Indeed, to read the editors’ annual announcements you would be forgiven for thinking that the Lady’s Magazine was the first magazine ever to have catered for a female audience, or to have celebrated female writers, or that it was the only, and certainly the most popular, periodical to have solicited reader contributions.

LM, XXXIV (Dec 1803). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

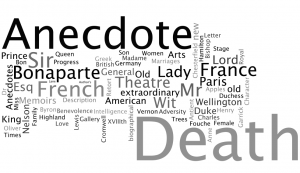

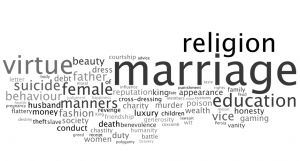

Yet for all its hyperbole, the Addresses contain vital information about this most enduring, yet elusive, of publications. They chart, for instance, the important shifts in style, composition and politics that characterise the magazine across its long print run and ensured its longevity. They document how a magazine, one of the main attractions of which in its first decades was its encouragement to reader-contributors to provide ‘original pieces of merit’, gradually gave way to a miscellany format in which the bulk was formed of ‘selections from the most valuable publications of the day’ for ‘those who have neither leisure not inclination to peruse voluminous and expensive works’ themselves, (LM, XXXIII [Jan, 1802]: 3). They signal the magazine proprietors’ and editors’ developing sense of who their audience was or could be. The mistresses and pupils of boarding schools, so important in the first two decades of the title’s history become marginalised post-1790, for example, while the need to produce elegant coloured fashion plates to keep up with reader expectations is taken as a given by 1800 . And they mark the shifting sands of the periodical’s aspirations as its call for a ‘revolution in female manners’, some 14 years before Wollstonecraft used the term only somewhat differently (LM XXVIII [Jan 1778]: iii), gave way to more modest hopes to satisfy ‘the delicacy and refined taste of the Fair Sex’ (LM, XXXIV [Jan 1803]: iii)

They also, in the absence of any known surviving publisher archive, offer up clues to such important and complexly related matters as: how many people read the magazine (in fact the only statistics we have to go on are those cited in the magazine itself); how the magazine was run; who wrote for it and why. Take just one of these questions by way of illustration. The identities of most of the magazine’s editors over the course of its nearly 70-year run remain obscure to this day. Editorial practice, however, becomes much clearer when the Annual Addresses are read, especially when they are read in conjunction with the monthly Correspondents columns. From these we see anecdotal evidence that what we might strongly suspect must, in fact, be the case: that a work so eclectic and yet, peculiarly, so coherent, had to be the work of multiple hands. We get glimpses of a succession of editorial boards, whose members were not always in agreement with one another, but the majority of whom believed in the magazine and had its best interests at heart.

LM, XXXIII (Jan. 1802). mage © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

Mostly, they testify to the powerful sense of community that the magazine held to be synonymous with its name. The Lady’s Magazine was, its editor or editors declared in 1781: ‘a Collection which is supplied entirely by Female Pens, and has no other end in view, than to cherish Female ingenuity and to conduce to Female improvement’ (LM, XII [Jan. 1781]: iv). Any reader of the Lady’s Magazine in the eighteenth or nineteenth centuries or now would struggle to dispute the centrality of and importance given to women’s lives, writing or wit to the periodical and these factors were surely two of the title’s principal attractions to its readers and contributors.

And yet almost every point made in this extract from the 1781 Address to the Public requires qualification. ‘Female improvement’ was undoubtedly a mainstay of the magazine, but the question of what constituted an improved woman and the best means to cultivate her talents were two of the most hotly debated topics throughout the magazine’s history. And if ‘Female ingenuity’ was cherished, as it certainly was by the magazine, then so too was that of men and boys, whose ‘Pens‘ provided a good deal of the content of the magazine’s pages, in fact rather more than we might feel comfortable with given its name.

Our project, amongst many other things, is working away in the interstices between the magazine’s rhetoric and what is recoverable about its reality. In this fascinating, if sometimes frustrating ongoing work, our best and most misleading resource is the magazine itself.

Dr Jennie Batchelor

School of English, University of Kent