Our regular readers will already know that the most important goal of our research project is to learn as much as possible about the thousands of readers who contributed to the Lady’s Magazine. Only last week, Jennie explained how she had succeeded in identifying two amateur authors, following hints within their contributions and in editorial notices about them. She found that these writers were personally invested in the magazine, and that it played a very important role in their lives. This was not the first time that we have blogged about such discoveries, and we will continue to do so, because we are always excited when we find out more about the relationship of reader-contributors to the magazine. What, after all, did they get out of their contributions? It was not money, because unsolicited submissions were in all likelihood never paid for, and although some ambitious authors may have used these first humble publications as a stepping stone, most left it at getting a few of their musings into print. The predominance of anonymity and pseudonymous or cryptically abbreviated signatures strongly suggests that the latter, larger category must in general have contributed solely for the sheer satisfaction of it. If this is the case, then it is puzzling why many readers felt the need to pass off as their own work material that had in fact been plagiarized.

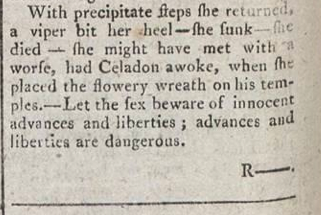

As I have discussed before, unacknowledged appropriation of contributions to other periodicals and, of extracts from books, was standard practice in the eighteenth- and early-nineteenth century press. Editors skimmed rival publications for quality content and employed hack writers to help fill up their magazines with copy that was taken from other sources, and to varied extents edited to make it seem original. This may have been unethical and even illegal, but commercially, it made a lot of sense. There is however little reason for unpaid contributors to pillage the creative output of others. Often, of course, readers would act in the capacity of what we have called ‘intermediate authors’, for instance when they recommend for republication certain items, mostly short poems or edifying extracts, gleaned from periodicals and books, and then usually they do so with a short prefatory headnote stating that they were not the author. In quite a few cases, however, some would simply submit plagiarized work. It is of course impossible to know whether this plagiarism was intentional, but at least there is no sign of any attempt to give due credit to the original author.

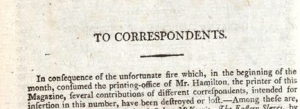

Today we have recourse to wonderful databases such as Eighteenth Century Journals, Eighteenth Century Collections Online and Google Books to detect the plagiarized contributions, but back then, editors had to rely on their own, obviously extensive, knowledge of contemporaneous print culture. With almost endearing hypocrisy, the Lady’s Magazine’s monthly correspondence columns do call out plagiarizing reader-contributors on such ‘petty Larceny’:

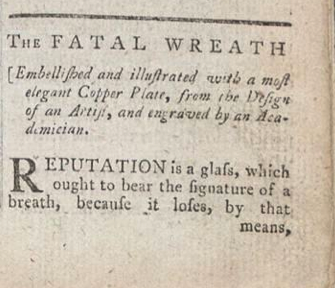

The angry letter from a Correspondent, signed Musarum Amicus, deserves some Animadversion : He threatens us with withdrawing his Favours from us for ever, if we do not insert a thing which he entitles, The Maid’s Soliloquy, a Parody, from Cato – By a Parthenian Lady; which, he knows, was inserted in the Covent Garden Magazine for March last — We might have excused this petty Larceny, had he addressed us in terms which were due to the Sex ; but when the Crime is aggravated by want of Delicacy, it deserves Resentment[.]“ (LM [July 1773]: 392).

According to the scholarly consensus on literary history, the early years of the Lady’s Magazine coincided with the breakthrough of sentimental verse, and much of the poetry submitted by readers does adhere to what Jerome McGann has called ‘the poetics of Sensibility’: literature primarily conceived as an attempt to record and communicate an individual’s ‘affects’, i.e. emotional responses to specific situations.[1] It is interesting that many of the poems plagiarized by reader were either (purportedly) personal lyrics, or ‘occasional verse’ meant to mark a specific event that impressed the poet, but that usually the only alterations are changes to the absolute specifics of settings or addressees. The following two examples are representative of the bulk of the plagiarized readers’ poems that I have so far managed to trace.

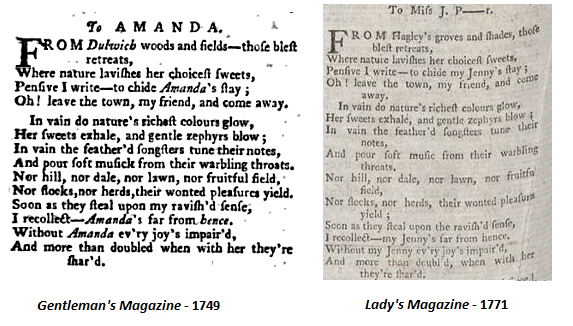

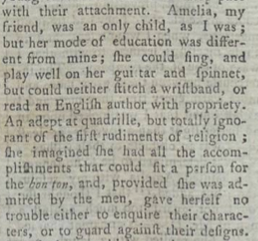

In January 1771, a contributor with the signature ‘Fidelis’ submits a melancholy poem of 58 rhyming couplets, dedicated to an absent friend ‘Miss J. P—r’ whose initial is revealed in the poem to stands for ‘Jenny’ (LM [January 1771]: 278-279). Cross-checking sampled lines with online databases has demonstrated that this poem is in fact an edited version of an original from the Gentleman’s Magazine of July 1749, signed ‘Sylvia’, and there dedicated ‘[t]o Amanda’. The juxtaposed opening lines of the two versions will show how very similar they are. Fidelis has made only minor alterations, changing the location from Dulwich to Hagley, and – luckily – not forgetting to change the name of the addressed lady either. Worcestershire, where Hagley is located, must in the eighteenth century have been remarkably similar to Dulwich’s Middlesex, as the ruminations on the original speaker’s surroundings seemingly did not require adaptation. It is worthy of note that the re-attribution of the poem from a female to a plausibly male signature (the nominalized adjective ‘fidelis’ is masc.) would alter the possible readings of the poem significantly. The poem in both versions contains the line (not in image) “Hail sacred Friendship! Virtue’s best defence”, which is intriguing in the original due to its female signature, but in the later version with male signature arguably less so.

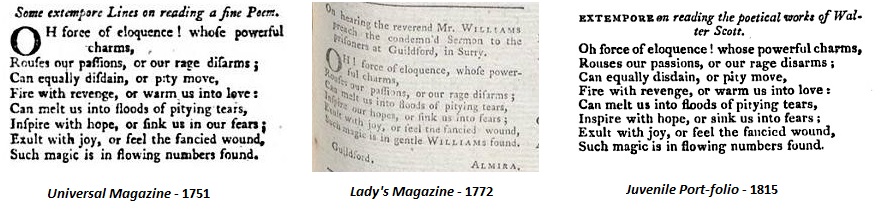

My second example is a short occasional poem that appeared in the Lady’s Magazine one year later (LM [September 1772]: 428). It was submitted by ‘Almira’, based in Guildford, to declare her rapture “[o]n hearing the reverend Mr. Williams preach the condemn’d Sermon to the prisoners” in that town. Again, a database search revealed that this poem is a but superficially edited plagiarism. The earliest version that I found is the unsigned ‘Some extempore Lines on reading a Fine Poem’ that appeared in the April 1751 number of the Universal Magazine. The Lady’s Magazine adaptation shifts the earlier version’s enthusiasm for the ‘eloquence’ of a poem to that of a preacher, who may have been the popular Dissenting clergyman John Williams (1727-1798).[2] The only differences are that the fourth line of the original is omitted, perhaps because it was judged inappropriate in a poem on a religious occasion, and in the new line 4 the adaptation has ‘sink us into fears’ for ‘sink us in our fears’. We can see how mobile contributions to periodicals were in this period from the fact that yet another version appears years later, in the American weekly Juvenile Port-folio of Saturday 4 March 1815. This version is nearly identical to that of 1751, but the anonymous plagiarist has changed the title to ‘Extempore on reading the poetical works of Walter Scott’. The Wizard of the North, of course, was not yet ‘warm[ing] us into love’ in 1751. Intriguingly, the 1815 version has the Lady’s Magazine’s reading ‘into fears’ as well. This suggests that there was another version of the poem, which may have been the original to all three versions, that has been lost or at least never digitized. We never can be entirely sure about the earliest instances of periodical contributions.

I do not believe that in either case the plagiarizers were conscious of doing anything wrong. Although reader-contributors to magazines did not have the same motives for appropriating the work of others as the editors had, the transgressions of both were rooted in the particular views on authorship prevalent in the eighteenth century. As is common knowledge, the notion of intellectual property was until the nineteenth century predominantly legal, and had not yet filtered through to the everyday ‘ethical order’ yet. I have discussed in an earlier post how, in contemporaneous satire on the hugely successful Lady’s Magazine, coy pseudonymous reader-contributors actually longed to be found out, as their masks would impart an elegant modesty to their authorship, adding charm to their contributions if they were recognized. This may well have been true for many, as locations in the dateline and references within the contribution were full of potential hints. In the same way that many magazine editors (I think genuinely) considered material found in rival publications to be up for grabs, there was for these amateur poets no ill in borrowing a line or two (or 58) from a more felicitous bard. The risk of getting caught would also be rather low. This must have been very convenient!

Dr. Koenraad Claes

School of English, University of Kent

[1] Jerome McGann, The Poetics of Sensibility (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), passim

[2] Diana K. Jones, “Williams, John (1727-1798)”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/29517?docPos=46 [last consulted on 31 Aug. 15].