In previous blog posts we have often pointed out that most of the original content in the Lady’s Magazine was furnished by reader-contributors. Encouraging unsolicited copy was an important part of the magazine’s strategy to obtain and consolidate a faithful readership, and this was obviously appreciated by these keen amateurs, many of whom would otherwise have had little chance of getting published. This diverse category included schoolchildren, but also women and men who were held back by disadvantages such as an unfavourable location far away from the centres of the British press, or the lack of a formal education. A major part of the attraction must have been the gratification of seeing in print one’s “lucubrations” (as they loved to call them), but what may surprise you, is that most reader-contributors did not sign their pieces, and those who did usually adopted strategies to ensure that their legal name was not, or not entirely, divulged. Many abbreviated their names, such as “J. T-t-w-e” above, or signed with their initials, and there are also a great many pseudonymous signatures.

Periodical scholars are interested in signatures because they are our main point of connection to the author of the texts that we read. They are important because, along with other factors, they frame the message of the contribution with which they appear. The same contribution by the same author but with a different signature would need to be read differently, because the author represents her/himself in a different way for often significant reasons: you could say that it might as well not have been written by the same person.

The most obvious and practical use of abbreviated signatures, initials and pseudonyms is to veil the identity of the contributor when full disclosure was deemed undesirable. To give a well-known example, in the eighteenth and nineteenth century several subjects were considered inappropriate for women, and female contributors could this way still participate in debates about these without losing their respectability. In December 1789 a (male) contributor hints at this possibility when he proposes to debate the differences between the sexes, by stating that having such a debate in the confines of the magazine is better than in public, because

LM XX (December 1789). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

In such ideological debates near-anonymous and generic pseudonyms are frequent. “A Lady” is commonly found, it of course being in the nature of signatures that we have no guarantee whatsoever that this is not the ruse of a moustachioed hulk of a man who wishes to sway the debate in favour of his own interest. Less suspiciously, reader-contributors regularly emphasize their sympathy with correspondents by signing themselves “A Friend”, and, to butter up the editor, “A Constant Reader” is also often used.

Apart from these prominent but not very amusing uses, pseudonymous publication also offer writers an opportunity for constructing a persona. Working on our index has already revealed to us some patterns in the monikers that reader-contributors chose to write under, and these can be highly fanciful. A certain “N. Cansick of Rathbone Place” usually signs his poems with this signature, sharing what is presumably his genuine legal name and place of residence, but for instance with letters to the editor he favours the more scholarly “Cansicus”. This suggests that for some contributors certain genres carried more prestige than others, and if Mr Cansick is just having fun, he would probably still at least be toying with such conventions. Reader-contributors also love to assume the guise of literary characters. Especially in the first decades of the magazine, we find several different “Belindas”, arguably referring to the heroine of the enduringly popular Rape of the Lock. Male contributors sometimes fancy themselves a pastoral “Corydon” or “Strephon”, and any literary(-sounding) name ending in –inda will do for some of their equally sentimental female counterparts: “Dorinda”, “Ethelinda”, “Clarinda”, “Clorinda”, “Lucinda”, “Imoinda”, “Merinda”, “Rosalinda”, and so forth.

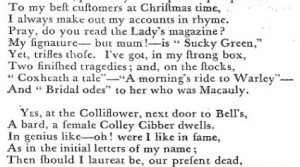

As we have seen before, the popularity of the Lady’s Magazine made it a frequent butt for satire in periodicals that aimed to be more highbrow, and the aspirations to authorship of the reader-contributors were of course an easy target. In 1779 the satirical weekly the Literary Fly featured an “An Elegiac Epistle” in which “Mrs. Catherine Carrot, Green-Grocer, at the Colliflower in Cornhill, next to Mr. Bell, Bellows-maker” gives her poetic account of topical events.[1] She ends by assuring the editor that she is not an ignorant woman, but in fact an educated and accomplished amateur poet. She hopes to have amply demonstrated this in her poem, “because these lines like Kitty’s shop are neat, / As her horse-radish sharp, her parsnips sweet”. This was not her first attempt at versification either:

The pseudonymous signature that this fictitious reader-contributor has adopted says a lot about what the Literary Fly thought of your typical amateur author in the Lady’s Magazine. According to the OED, one now obsolete meaning for “suck[e]y” was “maudlin”, and to be fair, in the late eighteenth century there was a lot of tearful verse in the magazine. “Green”, then, does not only suggest naïvety; just like her legal surname “Carrot”, it ties the poetess to her rather prosaic daily occupation, which she will never be able to escape. I am sure that none of the Lady’s Magazine’s amateurs felt that this slight applied to them.

Dr Koenraad Claes

School of English, University of Kent

[1] Carrot, Catherine [Herbert Croft]. “An Elegiac Epistle”. Literary Fly Vol. 1, Nr. 6 (Saturday 20 February 1799), pp. 29-34