Through our weekly posts we have been trying to keep you up to date on our progress in finding out as much as possible about the Lady’s Magazine. Although we are passionate about our research, we have also not resisted the inclination to have a little moan every once in a while about the many challenges that have sometimes kept us back. A scarcity of sources, the rather fundamental problem of not having a complete text for the magazine itself, you have read it all before. We have not done this to vent our pent-up rage. That, we do amongst ourselves, weekly over coffee. Rather, we hope that our troubles may be instructive to other scholars who want to study the Lady’s Magazine or other periodicals of its kind and time. After all, the problems that we face are characteristic of the whole of the periodical press of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century. The lack or disappearance of historical archives and artefacts is not the only issue. Certain clever ruses through which magazine editors sought to evade critical scrutiny into their publications in their own time can of course be even more troublesome to readers over two centuries later. In his study on the subject, E. W. Pitcher gives a long list of practices by which late-eighteenth-century magazines ‘indulged in subterfuge and marketplace subversion’.[1] I have recently started to research the ways in which the Lady’s Magazine repurposed material from other publications, both books and rival periodicals, and I have found these to be a case in point.

You may have anticipated that `repurposed` is a euphemism. Today we might be tempted to use a harsher term like ‘piracy’ or ‘plagiarism’ when referring to the magazine’s wholesale reprinting of second-hand material without acknowledgement. It is important to remember, however, that this was standard practice when the Lady’s Magazine was published. Although reader-contributors delivered a lot of original copy, like many magazines of its day, it partially fits in the category of the ‘miscellanies’. These were periodicals that contained a large amount of republished material. Although this internet-era jargon was of course not current back then, these periodicals were foremost purveyors of ‘content’, which is basically whatever a target audience will read and come back for. Long-running magazines could tacitly reprint old items from their own pages, like the Town and Country Magazine (1769-1796) which kept its greatest hits in circulation, and after a few decades, the Lady’s Magazine occasionally did this as well. More often, periodicals looked elsewhere. Rudimentary copyright laws did exist in the eighteenth century, and sometimes publishers did take each other to court, but it was an unwritten rule that you could get away with more in periodicals than in book publication. As long as it did not get out of hand, magazines stole from each other quite contentedly. This understanding is a direct result of the proliferation of the magazine genre during the second half of the eighteenth century. By now many titles were addressing the same, though wide readership, and the easiest way to keep up with your competitors is simply to follow their example closely when they are on to a successful idea.

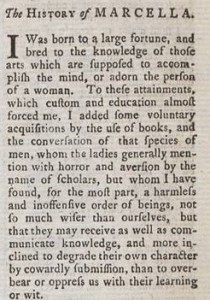

LM, I (March 1771). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

A frequently quipped motto in eighteenth-century periodicals was ‘multum in parvo’, ‘much in little [space]’, and this soon became the enduring philosophy of the magazine genre. This preference for having a large number of short items in each issue made it especially opportune to scavenge the ever expanding print market for bits of interesting text. Eighteenth-century magazines employed staff writers, pejoratively known as ‘hacks’, whose job was to do just that. If it was considered necessary, these authorial buccaneers would also alter the originals to various extents. The Lady’s Magazine in March 1771 shows how accepted this practice was by only changing a single name in an excerpt from Johnson’s Rambler, and copying the rest of it entirely verbatim as “The History of Marcella” (her original was called “Melissa”), without citing the source. The fact that readers might recognize the well-known original, which was still in print through collected editions, can therefore not have been a real concern.

The Lady’s Magazine also has thousands of ‘anecdotes’, of one or two paragraphs in length, and usually about historical figures. The sources for these are hardly ever given, but we would be very naïve to assume that they were gathered from the table talk at the editor’s club, or from discussions at the coffee house. These anecdotes are usually excerpts from books, either recent publications or older ones that most readers would not be overly familiar with, so that they had an illusion of novelty for the magazine’s reader. With the help of some online databases, I have for instance discovered that an “Anecdote of Elizabeth Petrowna, late Empress of Russia” (September 1770) is an extract from the then recent English translation of General Mannstein’s Memoirs of Russia, Historical, Political and Military (also 1770), though the magazine does not tell us so. The anecdotes are usually unedited excerpts, but sometimes they are paraphrased, likely to prevent readers from realizing that they were being fed repurposed content, and to put plagiarized rivals off the scent as well.

At times this appropriation of content is more blatant. A nine-part series in the first two volumes (1770-1771), entitled “The Lady’s Biography”, without any mention of this, consists entirely of slightly edited excerpts from the anonymous Biographium Faemineum: The Female Worthies (1766). Occasionally a phrase is tweaked, or one fanciful adjective replaced by another, but the magazine’s article series is undoubtedly a rewrite. Interestingly, such items tend to migrate across periodicals, often under different titles, as one plagiarism is in turn plagiarized in other publications. Periodicals have their favourite competitors to steal from, and this can teach us which publications aspired to be like each other. The Lady’s Magazine may have reprinted the work of others extensively, but its own commercial success is illustrated by how it regularly seems to have been at the start of a chain of piracies that are taken up by other periodicals consecutively. There is arguably such a thing as an ‘original plagiarism’. Some caution is needed, as other factors may influence this process too. The abovementioned Town and Country Magazine had strong links to the Lady’s Magazine because the two publications for several years shared their publisher, Robinson and Co. on Paternoster Row, and the fact that the same items often appeared in both periodicals at around the same time may indicate that already before the initial printing they would have exchanged material that was submitted to them, or produced by their respective staff writers. For all we know they may have shared the latter as well, as the records on the Lady’s Magazine do not reveal much about who it employed.

I also expect to find in the Lady’s Magazine the type of longer essays that Pitcher refers to as ‘paraphrase-and-excerpt articles’.[2] These combine elements from several sources into one ‘new’ text, travel narratives and accounts of foreign cities being a popular topic. These are very difficult to identify, as will probably have been the responsible staff writers’ intention. Unacknowledged translations that appear nowhere else than in the magazine, mostly from French sources, are also elusive because it is not always apparent where you need to look for  the original. A translated excerpt from Voltaire’s L’Ingénu (1767) is properly credited in the August 1771 issue, maybe because the author’s name was a selling point, but in the same year several translated tales from the less famous Denis-Dominique Cardonne’s Mêlanges de Littérature Orientale (1769) are not.

the original. A translated excerpt from Voltaire’s L’Ingénu (1767) is properly credited in the August 1771 issue, maybe because the author’s name was a selling point, but in the same year several translated tales from the less famous Denis-Dominique Cardonne’s Mêlanges de Littérature Orientale (1769) are not.

Needless to say, the Lady’s Magazine is generous with information when the excerpted original had been published by its own publisher Robinson, and will often indicate in the rubric that the work in question has been ‘recently published’. This makes the excerpt to all ends and purposes an advertisement. Like most of its competitors, the Lady’s Magazine also contained more straightforward announcements of books by its own and other publishers, and starting from the early nineteenth century also regular book reviews, which include long excerpts from the discussed work that function as self-contained texts. The verdict of the reviewer is limited to an introduction of a short paragraph to recommend the excerpted work to the reader’s attention, and the profuse quotation that follows makes this type of article a cunning form of republication too.

The results of my ongoing research into the sources for repurposed content in the Lady’s Magazine, and the sometimes surprising publications where its own original contributions ended up (maybe a topic for a future post?), will eventually be added to our annotated index. In the meantime I am going to have lots of fun trying to catch the crafty staff writers at their tricks.

Dr. Koenraad Claes

School of English, University of Kent

[1] Pitcher, E. W. An Anatomy of Reprintings and Plagiarisms. Lampeter: the Edwin Mellen Press, 2000. p. 2

[2] idem, p. 90

thanks for posting.

thanks for posting.

The magazine also routinely “borrowed” fashion prints from other magazines. Up until about 1804 or 1805, all their prints were based on fashion prints from the French publication Journal des Dames et des Modes. They weren’t EXACT copies, but very very close. They did “acknowledge” the borrowing by giving each print the title “Paris Dress.”

As you say, The Lady’s Magazine was just doing what every other periodical did. Almost all British magazines that included fashion prints “borrowed” prints from the French edition of Journal des Dames et des Modes: Fashions of London and Paris, Lady’s Monthly Museum (which lifted prints from everywhere), La Belle Assmeblée, Le Beau Monde, Ackermann’s Repository of Arts, etc.

Candice Hern