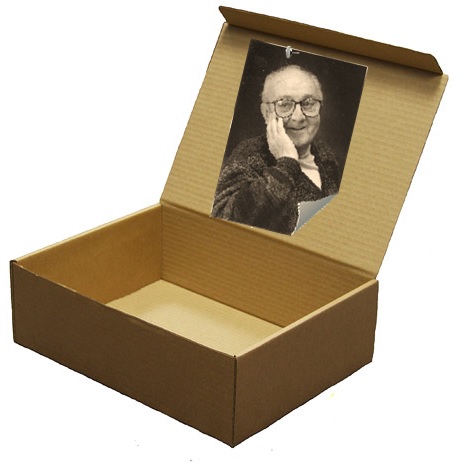

This day one year ago (March 28th 2013) saw the death of one the country’s most quietly influential exports, Professor George Box. Born just after the first world war in Gravesend, Kent and attending University in London for both his batchelor’s degree and his PhD, he ended up spending most of his life in the USA.

This modest and witty Kentish man, who stumbled into the world of statistical analysis is now considered amongst the top ten statisticians of all time.

I recall seeing a George Box presentation at the 1995 First World Congress on Total Quality Management in Sheffield; he described how industrial progress has been based on increasing knowledge and systematic design (he used a schematic of historic developments in shipbuilding to which I have often referred people to illustrate this point).

As a statistician made famous for the development of models to better describe phenomena, Box’s most memorable quote was:

“essentially, all models are wrong, but some are useful”

If you come across a model, remember it is just that – something to map onto your mind to help make sense of things. If the model helps, make it something useful to you – by using it. But don’t waste time picking small holes in things – ‘worry selectively’ as Box would say. There is no ‘best way’ to see anything, but if there are fundamental flaws in a model, or it is useless, then drop it. As much as not worrying about everything, there is also little time to keep flogging dead horses!

Reading:

Box G.E.P. (2013) An Accidental Statistician, Wiley-Blackwell

Jones B. (2013) George Box: a remembrance. http://blogs.sas.com/content/jmp/2013/03/29/george-box-a-remembrance/

The idea of ‘culture change’ has been around at least since the 1970s.

The idea of ‘culture change’ has been around at least since the 1970s.