We have had an unusual year due to the effects of the pandemic across the globe. We were very fortunate to be able to carry out much of our teaching in person, in accordance with government regulations. However, the pandemic did impact Paris and its residents, an experience of which our own Dr Frances Guerin has been exploring in her writing. Dr Guerin has shared her time between Paris and Canterbury since 2006 and teaches in the Paris School of Arts and Culture’s Master’s in Film and the History and Philosophy of Art. We recently sat down with Frances, thankfully face-to-face in a Parisian café, to discuss her impressions of the pandemic and how she transposed these into a series of essays. Join in our discussion with her and read one of her essays, “The Things I Need” below.

PSAC: How did you feel when the talk of the pandemic started going around?

FG: I was actually on a student trip to Rome when talk of the pandemic started to become much more frequent. The week before, it had begun to ravage the north of Italy, but in Rome, there was sign of it. The man at the hotel in Rome dismissed it. He said one night, “Can you believe, they’ve shut things down in the north of Italy? There’s no way we could do that here. We would all go out of business.”

Then a week after we got back from Rome, the lockdown was announced in Paris. I was having lunch with friends on a Saturday afternoon, and it was like Christmas day. The streets had emptied out, many places were already closed and we were the only ones left in the restaurant. After lunch, I went to the movies, and there were only a few other people in the theatre. I was going to see a second film, but the security guard stopped me, explaining that the cinema was closing because “the virus is coming.” And that was it. It was a very strange experience because I honestly thought that it wasn’t going to come to Paris. How could Paris ever shut down?

The thing for me that was most difficult, beyond being stuck at home and having to teach on Zoom, was the policing. I had never experienced anything like it. I lived in Cold War Moscow, so I know how totalitarian states operate, but it was nothing like this. In Cold War Moscow I was a foreigner, so no one was looking at me. Plus, surveillance is much more clandestine. I had never experienced checkpoints, police standing there with their rifles, and then cruising around, stopping people randomly, demanding documents. I found it very unsettling. It was pretty intense.

What was it like for you during the various confinements?

To start off with, it was sort of a novelty. But after a week or so, that began to wear off. It became very time consuming when we had to get everything onto Zoom suddenly, overnight. I was very much caught up in all of that to begin with. During the first confinement I enjoyed the time and space; I had my own Joan Crawford festival, at home, and then a Jean-Pierre Melville festival. I re-watched all their films.

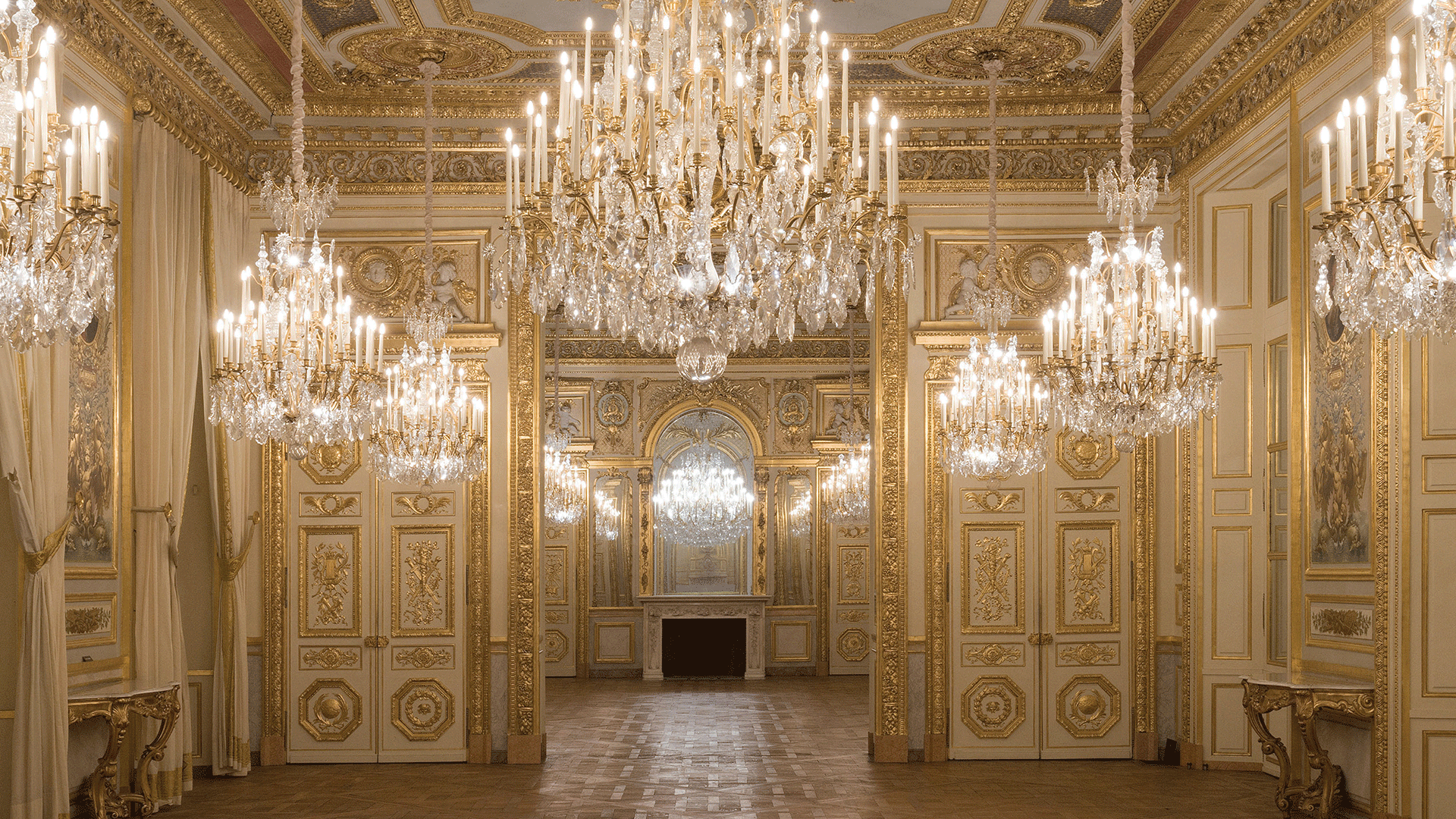

One of things that I found most difficult was that we were so regulated. The fact that we were only allowed to be one kilometre away from home, for one hour, and had to carry paperwork at all times. No one in my international global community really understood just how constricted we were. It was very isolating. I don’t think I’ll ever take for granted sitting across a table in café with another flesh and blood human being, like we’re doing right now. Because without that life became empty. And art, I missed going to galleries and museums, the BnF and the movies.

By the time we had the second and third confinement, we were sick of sitting in front of the computer, of Zoom meetings. we had to stay at home, but it was different. The government had introduced nighttime curfews, but we weren’t policed to the same extent—even though we still needed all the paperwork.

In the second confinement I didn’t watch any movies. I didn’t want to sit in front of the computer for longer than I had to. During the second confinement it was winter, so it was cold, wet and dark. So it was pretty depressing. It was difficult, and felt like it went on for a long time. That said, luckily, we were able to go back to the classroom, which made so much difference. Having contact again with students was great.

Then by the third confinement, the vaccines had arrived. Even if vaccines hadn’t really taken off in Europe, we were watching the UK get vaccinated and their numbers dropping. This gave a sense of hope that an end was on the horizon. Still, by the end, I really yearned for museums and movies.

How did you express yourself creatively during this period?

I actually wrote two books. The first is a book on Jacqueline Humphries, a contemporary American painter. I went to New York and met her in her studio in January 2020, so luckily, just before the pandemic hit. It meant that I was able to write a first draft of the book last summer. In the winter (before the second confinement), one of her works was on display in a gallery in the Marais, and was lovely as I got to go and see it. The book will hopefully be with my publisher in about a month.

The other book is a series of essays on living with the pandemic in Paris. I’ve always been interested in imprisonment. I had this Russian thing in my blood, I learnt Russian, I lived in Moscow and I was always really interested in works of Russian literature. So many of them have a focus on imprisonment. Dostoyevsky’s Raskolnikov is, for all intents and purposes, a prisoner. So are the brothers Karamazov. Prisoners in space or in the mind. I’ve read a lot of books about incarceration, and how to stay alive. It’s all about keeping the mind and alive when the body only has a certain space in which to move. I thought a lot about books like Bernard Malmud’s The Fixer in those first weeks. Of course, we weren’t imprisoned, but I don’t think many people can imagine what confinement was like in Paris, being trapped inside these small spaces for 23 hours a day. Because I’ve always had this fascination with being incarcerated or enclosed in a small space, my writing group said, “This is your moment.” They were ones who encouraged me to write about it.

Tell us a little more about your confinement series?

There are 24 essays in the series, and the first one I wrote was this incredible experience of teaching first year students before any of us really knew what we were doing on Zoom. In one of the first classes, I had Zoom bombers. To this day, I still don’t know who they were. The story became about how the ways that we are “present” in the world, attending class and meetings for example, completely changed. It was a really fun story about this bizarre situation we were living in.

The second one I wrote was inspired by looking at the clutter in my apartment for 23 hours every day. I kept thinking about all about the things I needed to throw away. I remembered Tim O’Brien’s story, “The Things They Carried,” about soldiers during the Vietnam War. In O’Brien’s story, “things carried” refers to the psychological, the emotional, the memories as well as they things they actually had in their packs. I was inspired to write a story about the things I need. It was, of course, very tailored to this world that we’re in. I needed an attestation (the government document proving our identity, when we left home, where we were going), I needed a light globe in my bag in case I got stopped. If the police asked me where I was going, I could say that I needed to replace the light globe and none of the shops on my block had the right kind. Therefore, it was reasonable that I be on the street.

Were you ever controlled?

No, but that isn’t the point, I don’t think. We internalise the possibility of being stopped, and that keeps us obeying the law. It’s how government surveillance works.

When did you start the stories? And when did they end?

I wrote them for a year, from March 2020 to March 2021. From the first lockdown to the vaccine rollout. These stories reach beyond that year though because they weave in films and artworks and books, and imagine how characters in fiction and film would survive in a pandemic. Like Vermeer’s lacemaker, who I assume would have been busy making masks. The stories also weave in racial tensions, questions of death, living under curfew as a form of state control. They are also about familiar French cultural customs that bubbled to the surface. For example, one of the stories is about the senses and how people lost their smell and taste in the Coronavirus, and were prohibited from touching. We were relegated to looking, but even then, we could only look from our apartment windows. In the story, I ask what does it mean to be French and not kiss each other on the cheek when we meet? And how are we meant to be together when we can’t eat around a table? How is French life meant to go on without these age-old customs?

Thank you for sharing your thoughts with us, Frances!

You can read one of these thought-provoking essays, “The Things I Need,” below . Two others have been published online, “Still Moving” on the site Her Stry and “Grieving,” which was published in the anthology Lockdown Literature.

Now that museums are open again, Frances is back going to exhibitions. You can read about her visits on her blog, Fx Reflects.

The Things I Need – by Frances Guerin

I need to live in a big city. Surrounded by culture, holidays in the sun, long runs in the morning. I need a library to work in, vibrant streets to walk down, and stimulating people for conversation in cafes. I am convinced I need all of them. I can’t possibly live without dinner in a neighborhood bar after a night at the movies. The convenience of the shop on the corner, the bike shop across the street, the airport at the end of the metro line. What’s the point of living in Paris if London, Rome, and Berlin aren’t within easy reach?

I look up at my building as I cross the street one night in mid-March. The lights in the windows remind me of an advent calendar. My neighbors are all home, dutifully watching the President’s speech on live television. Inside my apartment, I check the news and discover that my view from the outside will be prohibited for the foreseeable future. The following day we go into confinement.

Checkpoints spring up all over the city. The police are out in full force. Under the law, we are required to carry a self-declaration, swearing we are who we say we are, our birthdate and place, our reason for being on the street. As an Australian trained in the art of dismissing authority, I find the declaration that I am out running when I am out running to be absurd.

For expats like me, raised with a relatively simple and accessible public service, French bureaucracy is labyrinthine and overwhelming. The bureaucrats can be frightening, demanding documents that are not listed as requirements. If we dare to question the request, we risk verbal humiliation. My cultural dislocation is never more marked than when I am face to face with the bureaucracy. This latest directive, however, trips over into the ridiculous.

I post an update on Facebook, entertaining my friends with the comical details of French government regulations. I laugh out loud when a colleague leaves a comment about having to complete paperwork to take her dog for a walk.

A French friend reminds us, “Without the paperwork, everyone would ignore the order.”

I can’t tell if she’s irked by or expressing solidarity with our mockery of French bureaucracy.

“We French agree, it’s a farce,” another adds.

“You can write in pencil, carry an eraser, and change what you have written if you are stopped by the police,” someone suggests.

“The prefecture posted on Twitter that pencil is not allowed,” the next warns.

“You can use the same form every day;”

“That’s definitely not allowed;”

“How do you know?”

“I read it somewhere…”

“Where?”

“I can’t remember.”

My post attracts forty-eight comments, debating the cans and can’ts of how to fill in the declarations.

The novelty of restrictions, paperwork and tweeting questions to the French police wears off quickly. I am stuck. I gaze for hours at the four walls of my room. I see the same objects over and over again. Staring at me, face to face. The objects I have collected are like people, alive, things with which I have relationships. Our relationship takes energy, making demands on my time.

I am reminded of the soldiers in Tim O’Brien’s stories of Vietnam. Of the things they carried in their packs, each is carefully chosen. The things have a physical, psychological, emotional and mnemonic value. I am like a soldier in the jungle; I keep things close, not just for their use value.

Sitting on my sofa for hours each day, I start to see all of the things I can live without. I don’t need the trinket box that my friend Vincent brought me from India. A little pink box covered with mirrored sequins, sparkling stones, and crafted beads. Inside, the coating is starting to peel off a string of fake pearls, and the clasp has been broken since my friend Cathy’s son opened and closed the box too many times. I have held onto memorabilia like this for years because I love my friends. Vincent is no exception. I might upset him if I throw away this treasure that nevertheless means nothing to me. In confinement, I need more space for me, less for my junk. Why not throw it away? He’ll never know. Perhaps I had better keep it? After all, this time will come to an end and, one day, we might be allowed to venture into the streets. Then again, the Eurostar won’t run between Paris and London for people like us. Vincent, the maître D in a fancy London restaurant isn’t coming to visit any time soon.

I come to my senses; Vincent will still be my friend when the trinket box has been moved to the underground archive for dead souls. Otherwise known as the rubbish dump.

I don’t need the birthday cards from my mother’s best friend, carefully written in a faltering script, some words gone over again and again. I wonder if the hesitation comes because she forgets how to spell the words. Perhaps it’s an indication that her hand can’t keep up with her mind, or the other way around? Either way, Gwenda certainly won’t be visiting to check that I have kept her cards. She’s 95 years old. She tells me regularly that she doesn’t need to travel again.

“I’ve already seen the world. Besides, I don’t want to pass through security,” she says in a matter-of-fact tone. “All that poking around in my bag, patting down my pants. It’s an invasion of privacy. It never used to be like that. I don’t need to go anywhere, I’ve seen the world already. I’m 95 you know. I don’t need to go through all that at my age.”

As confinement wears on, my sofa becomes increasingly comfortable. I start to agree with Gwenda. Maybe I don’t need to travel. I go jogging daily at the government prescribed hour for exercise. In the remaining 23 hours, I move from the shower to the desk, to the sofa, to the kitchen, to bed. The next day, I trace the same steps all over again. By the end of each day, I am exhausted. From one room in my apartment to the next, that’s clearly all the travel I need.

Gwenda tells me on FaceTime that she has no need for anyone to do her shopping while in confinement. “I can do it myself. I couldn’t think of anything worse than having someone pressing on my peaches and pawing my peppers. ”

“Wouldn’t it be nice to have your groceries delivered?” I ask. I recall reading that Australian confinement regulations state that over-75s are not allowed to leave their homes. I chuckle at Gwenda’s disobedience.

“Goodness, no. That’s just for old people,” she retorts.

I understand Gwenda’s logic. In confinement, the supermarket has become the most exciting outing of my week. Okay, I admit. Morning run aside, it’s the only time I leave my apartment. Like Gwenda, I am not about to give up a weekly trip to the supermarket. It’s more than a necessity. It’s an imperative. I look forward to the 350-meter walk. Across the boulevard, down a side street, around a corner. It’s the same every time. I stand obediently at the back of the line, a meter away from the person in front of me. The anticipation of my weekly shop makes me restless.

Inside the doors, it’s a different story. I don’t want to be there. Caught in the cramped aisles lined with empty shelves, I am pushed by the woman who needs the last bottle of almond milk on the shelf, the man whose arm goes over my head, reaching for the cheese with the newest use-by date. Another man coughs and everyone scowls. I take a step back, alarmed. The air is surely raining Covid droplets. I glower at the man and, almost immediately, wish I hadn’t. I despise the practice of shaming the sick. But I can’t help myself.

“Why didn’t he stay home?” I ask the woman behind me.

“Excuse me, do you mind watching my trolley? I forgot the carrots,” she responds politely.

I was expecting a different response, like, “How dare he” and a roll of the eyes, for example. One nice word to a fellow masked alien shopper, and she thinks we are sisters in arms. No, you don’t understand, the man over there coughed, I want to bark back. Instead, I nod politely and ignore her trolley. I am beginning to understand that what I need is different from what I want.

I do need the UK to keep functioning because Her Majesty’s government pays my salary. I tune into the BBC World Service for regular updates on the UK lockdown. It becomes obvious that no one needs the British Prime Minister. If he was indispensable, he wouldn’t have spent so many days and nights in hospital. Come to think of it, I can do without his advisers as well. Obviously. The British instructions for isolation are so convoluted that no one can follow them. If this, then that … yes go there, but only when … or if you have a reasonable excuse. Drive the car, but only on the condition that the distance you walk at the destination is greater than that you drove to get there. Pages of instructions successfully confuse anyone who tries to follow them. Brexit means Brexit, but Stay Home can mean anything you like. I rethink my need for the BBC; it’s no more than a mouthpiece for the government’s obfuscations.

By contrast, my next visit to the supermarket confirms that I need the man at the entrance to squirt a glob of hand sanitizer in my open palms. He’s more important than the man who is supposed to be running the United Kingdom. Apparently, I don’t need to know the scientific explanations for the R factor, the curve exponents, the percentage of infections per capita. But I do need to know that the apples I touch, and don’t buy, will be clean for the next anonymous shopper.

My shopping basket brushes the leg of a woman in a mask. Her muffled voice is filled with heated emotion, sucking the mask to her mouth to create a concavity in the fabric. I don’t understand why she is upset. I want to ask her to remove the mask, but I don’t need to know what she is saying. I ignore her and go in search of the charcuterie.

It’s day fourteen, and I am running low on coffee beans. For over a decade, I have bought coffee at a small local store. I stop in the coffee aisle at the supermarket and stare at the array of vacuum-packed home brand beans. What do I do? I turn the question over in my mind. My coffee shop won’t be open, so maybe I should buy it here? But then, I can’t drink supermarket coffee. It won’t be the same, it won’t wake me up, it won’t, it won’t, I can’t, I don’t want to. My thoughts fall into a spiral of despair in the coffee aisle. A child pulls the packets from the bottom shelf. Time to leave. I don’t need the coffee.

Two days later, I happen to pass the coffee shop during my one hour of government-sanctioned exercise. The door is ajar, and I see the man behind the counter, bent over huge hessian bags filled with coffee beans. I feel my heart expand, my mood lift, I sense a smile light up my face. I breathe relief. My sensory receptors are aroused then invigorated by the rich, seductive smell of freshly ground coffee. I approach the counter, cautiously. Inside the small shop it isn’t possible to stand at the government-dictated distance.

“I didn’t think you would be here,” I gush with excitement.

“We are classified an épicerie,” he responds nonchalantly. The man starts to fill a packet with my regular roast. “One kilo? Ground for a French Press?” He asks in a voice that supposes nothing has changed since the last time I saw him.

“Yes, yes. Have you been busy?” I ask. I have so many questions, my heart starts racing.

This is the first conversation I have had with a real person in sixteen days. Not counting the perfunctory exchanges at the supermarket. On day one of confinement, my upstairs neighbour texted to say she was sick. My interactions with her have become reduced to a handful of blank declarations on my doorstep every few days. Some evenings her partner and I yell a few pleasantries from our windows at 8pm, in between applause for the frontline workers.

I might want coffee, but it’s not my first need. I can live without coffee. Flesh and blood contact with another human being is a basic necessity.

“I hate the isolation,” I confess to the man at the coffee shop. This banal conversation engages every part of me as I realize my discomfort out loud for the first time. “The restrictions are ridiculous,” I moan.

“You are not the only one,” he responds with a smile. He pours the coffee beans into the grinder.

“Really?”

“Ah, but of course. Everyone is frustrated. And the police with their petty exercise of power, giving out fines at every turn.”

“Did others tell you that?”

“Oh, of course, what do you expect? We all hate it.”

I walk home with a spring in my step, swinging the bag of coffee with delight. Our short conversation keeps me going for hours, knowing that there are others who think like me. I feel so replete having had a real conversation, with a real person, not just an image on a screen.

I need my computer. I wish I didn’t. To be connected, I must have a screen between me and the world, my ears hidden under headphones. I raise my virtual hand in a request to speak. It all seems like a silly science fiction movie. This isn’t funny, I remind myself. I think of all the people who don’t have a computer and an internet connection, let alone an apartment.

I think of the Vietnam soldiers in O’Brien’s story, carrying their life on their back, and those of their ancestors in their veins. I think of the weight of munitions belts, the memories that keep fantasies alive, and the ghosts of dead comrades that crushed their ability to hope. The things they carried to kill or to keep them alive. Whichever was needed most.

Confinement in Paris is a privilege. My worries are a luxury. Stop complaining.

I turn my thoughts to the bright side of my new life on Zoom. I enjoy seeing inside my colleagues’ apartments, how they live, little granules of information to tell me who they really are. It doesn’t occur to me that they, like me, might have staged their apartments for the camera.

My colleagues tell me that the world is going to change, and I won’t be able to have dinner dates any time soon.

“You won’t ever travel to Italy again,” warns a grumpy older colleague.

I will be stuck here in front of the computer for the rest of my life. I panic. My thoughts get in the way, reminding me that I need a bigger apartment, a better job, one more pair of shoes, and the sweater I tried on while wasting time, waiting for my train at St. Pancras in January. I am convinced that I need more money, more prestige, more admiration. My mind races with all of the things I need and the people I must impress if I want eternal happiness. Here in front of the computer screen.

A siren echoes outside my window as an ambulance speeds down the boulevard. It reminds me that the thoughts cluttering my head can go in the trash. They belong with the old birthday cards and the pink trinket box. No one else needs to know they ever existed. I certainly don’t need them.

I wake up to a WhatsApp from a dear friend in New York “Darling, how are you getting on in Paris?”

“We are in total confinement. You?”

He sends me a selfie with his girlfriend in the middle of nature, followed by a message, “Social distancing in New York.” He adds a winking emoji.

I feel the rage rise inside of me. It’s not fair. I am only allowed out for one hour a day, and if I don’t have paperwork, I will be fined. At worst, I will be put in jail. I definitely don’t need to be communicating with my New York friends.

I need to find a way out of Paris. Take me away from this isolation. Fantasy will do.

Day twenty-one and the man at the door of the supermarket is still there holding the bottle of hand sanitizer. The coffee man shuffles behind the counter at the same pace, in or out of confinement. Zoom is starting to irritate me, but the computer remains my doorway to the world. I have a connection. That’s all that matters.

It’s the beginning of the second month in confinement, and I am learning to reformulate my wants and needs. I need air, water, food, a bed to sleep in, a roof over my head, a computer and a bag for my groceries. In my bag, there’s a dead light bulb, a spare pair of glasses, and a blank declaration form, just in case. I’m always hoping to find a replacement globe for the unusual American lamp in my living room that was given to me by a friend when she left Paris. I obviously don’t need to turn the lamp on because the globe has been dead since confinement began, and the supermarket doesn’t carry the particular variety. I also keep a pen in my bag. Heaven forbid that I get caught in the street beyond my one permitted hour, my one permitted kilometer. I remain vigilant. The thought of the police stopping me, checking my papers wartime-style, mathematically determining that my time has expired or I have breached the limit of acceptable distance from home. In the remote past of February, a pen was essential for freedom, inspiration and jotting down ideas in my notebook. Now, I need the pen more than ever, but for reasons I could never have imagined. In this brave new world, a pen is for changing the time, or filling in a new form if caught by the police.

I need the garbage collected. I think back to the film, Contagion in which social disorder and eventual anarchy sweep through the streets of America. It all begins when the garbage spills out onto the streets.

Bless that man who comes on his motorbike every Tuesday and Friday to put the bins outside, returning two hours later when they have been emptied. No one in my building speaks to him, perhaps because they can’t understand his accent. I said hello to him a few years ago, and he looked at me through the visor of his helmet as if I was from outer space. I don’t dare try again. I remain silently grateful that he fulfils one of my most important needs.

Routine is essential. I need to run every day, keeping my mind as well as my body from falling into disrepair. I don’t need and I don’t like the woman who yells at me from the other side of the street, behind a mask. I never understand what they are saying when a mask is involved. A man walks towards me, noticing the puzzled look on my face, laughing. He explains that the woman doesn’t want me out running, despite the fact that I am following the law. It is 9.30am, the shops aren’t yet open, and she is yelling at me. I am tempted to turn around and scream at her in my smartest French. It’s what she deserves.

“Go take your anger out on smokers, car drivers, and all the others who pollute the air you breathe.” I practice my retort in my head, making sure to get the grammar correct. I say nothing. I keep running.

It turns out that the things I need are not the same as the things that clutter my life. I discover that it’s not the objects that I stalk on the internet, like books, pens, inks and bikes that I need to keep me going. I need new running shoes, but old ones will do. I need books, but I have enough for years in confinement. I thought I couldn’t live without nail varnish, that dress I’ve been eyeing in the shop window across the street, and Wednesday nights’ new releases at the cinema. Apparently, I need none of these. Who would have thought that the British Prime Minister, dinners with friends, and proximity to the train station would no longer matter.

What will the world look like when this crisis is over? Will it ever be over? I have no idea. What I do know is that whatever happens, I need to trust. I need to know that all will be okay. I also need a regular reminder that I can’t plan for the end. That doesn’t stop me from trying. When will it end? What will the end look like? Who will I be when it’s over? How will I get there? Enough.